By Adam Pagnucco.

Here’s a question that has come up over and over again with various candidates and potential candidates: should they take public campaign financing if running for county office? Your author’s typical practice is to demand provision of food and/or liquor in exchange for answering this question. But in the spirit of recent holidays, we are just going to give away our take right here. Feel free to send liquor anyway!

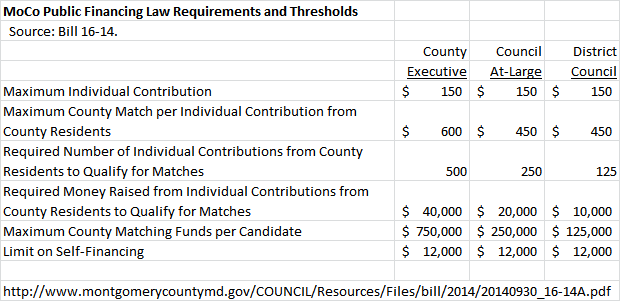

First, let’s explore the basic characteristics of the county’s public financing system. Candidates who wish to participate may opt in, but it is not required. Candidates in the system must establish new public financing accounts with the State Board of Elections and any money in their old accounts cannot be used for current election expenses. Contributions may only be accepted from individuals at a maximum of $150 per donor. Corporate and PAC contributions are forbidden. Self-financing is limited to $12,000 from the candidate and/or a spouse. The county will match contributions made by in-county residents on a sliding scale with maximum amounts of $600 per donor for Executive candidates and $450 per donor for council candidates. But to qualify for matching funds, candidates will have to meet certain thresholds in terms of number of in-county contributors as well as amounts contributed. These thresholds are shown in the table below.

Now here’s the Big Question: do voters care about who uses public financing? No one knows because 2018 will be the first cycle in which it will be available. But while public financing is new, discussion of campaign financing is ancient. Developer contributions to County Executive and County Council candidates were a huge issue in the 1990s and 2000s. Citizen groups like Montgomery County Citizens’ PAC for the Future (CITPAC) and Neighbors for a Better Montgomery (NeighborsPAC) tracked and published them. These groups, which have no successors today, formed a political base for anti-growth candidates who vowed to limit or entirely refuse developer contributions. The result? Most of the candidates who won the 1998, 2002 and 2006 elections took developer contributions freely, including Doug Duncan, Ike Leggett, Steve Silverman, Mike Subin, George Leventhal, Nancy Floreen and Mike Knapp. Phil Andrews and Marc Elrich were the primary exceptions, though Elrich lost four straight times before finally winning in 2006. If most voters viewed developer money as something that would determine their votes, candidates supported by CITPAC and NeighborsPAC like William O’Neil, Vince Renzi, Ann Somerset, Hugh Bailey, Cary Lamari, Sharon Dooley, Cynthia Rubenstein and Chuck Young would have been elected. It’s unclear whether the politics around public financing will play out any differently.

And so the appropriate criteria for whether to enter public financing relate to the self-interest of the candidate. In which system will you be better off? That depends on your own circumstances and the nature of your race. We’ll start addressing that in Part Two.