By Adam Pagnucco.

Former Council Member Phil Andrews’s public financing system is in use for the first time during this election cycle. It has already changed MoCo’s political landscape, with 33 county candidates – a majority of those running – so far enrolled. It’s a bit early to say exactly how it will impact specific races, but two facts about the system are starting to become clear.

It’s cumbersome to use. And candidates who use it need a long time to raise money.

We have already written about the burdensome administrative aspects of the system, especially in demonstrating residency of contributors. (The system only provides matching public funds for in-county individual contributions of up to $150 each.) An additional difficulty is meeting the thresholds for triggering eligibility for matching funds. In order to collect matching funds, Executive candidates must receive contributions from 500 in-county residents totaling at least $40,000; at-large council candidates must receive contributions from 250 in-county residents totaling at least $20,000; and district council candidates must receive contributions from 125 in-county residents totaling at least $10,000.

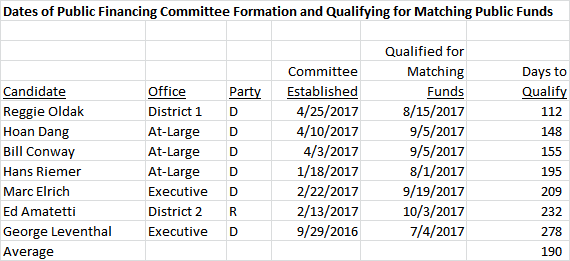

So far, just seven of 33 participating candidates have reached the thresholds for public matching funds. Council District 1 candidate Reggie Oldak was the fastest to qualify, hitting the threshold in 112 days. But Oldak is a district candidate, meaning that her threshold is the lowest, and her district is the county’s wealthiest with the greatest concentration of political contributors. At-large council candidate Hoan Dang hit his threshold in 148 days, barely beating out Bill Conway (155 days). Council Members Marc Elrich and George Leventhal, who are running for Executive, needed more than 200 days each to qualify despite having large donor bases going back many years.

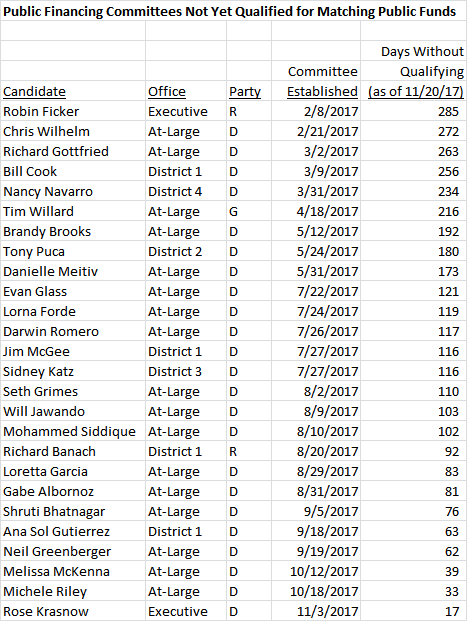

Then there are the other 26 candidates who have not yet qualified. Six of them have been running for more than 200 days. (District 4 incumbent Nancy Navarro will only be eligible to receive matching public funds if she gets an opponent.) Eleven more have been running for at least 100 days. Many of the non-qualifiers have been working hard for months. It’s just tough to meet the thresholds.

Why is it taking so long to get matching funds? One reason is that Andrews, the system’s architect, did not design the system to be easy. He explicitly intended that public dollars only go to candidates who were viable in the sense that they had actual grass-roots support. Another reason is the nature of fundraising itself. Candidates who raise money turn to families and close friends first; past contributors next (if they have run before); then extended networks of professional connections, acquaintances and supporters’ networks; and finally complete strangers. As each network gets further away from the candidate, the marginal difficulty of raising dollars increases. In a public financing context, the first fifty contributions are easier than the next fifty, which in turn are easier than the fifty after that. The last few contributions to reach the threshold are the hardest to get.

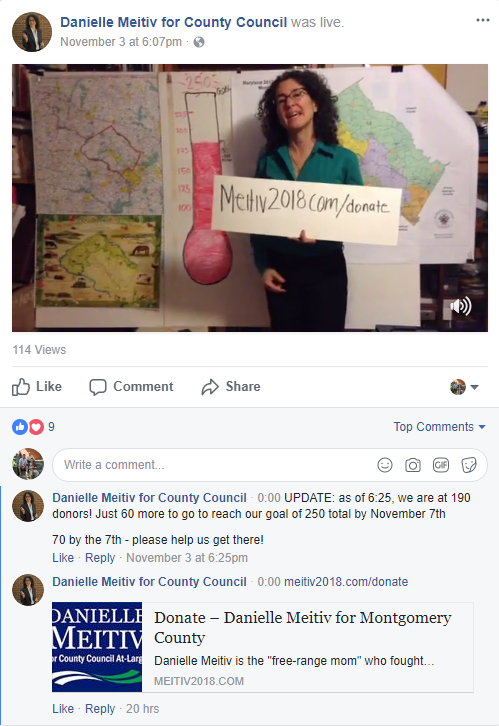

At-large candidate Danielle Meitiv has been working to hit the threshold with a video on Facebook.

Similar observations can be made about traditional fundraising with this exception: the private system has no single trigger that activates a stream of cash all at once. The candidates in public financing will be weeded into two groups: the ones who get matching funds and the ones who don’t. The latter group will be doomed to failure.

There’s one more lesson here for candidates: don’t get into a race late and expect to raise lots of money quickly through public financing. Even if you have a history of donors going back more than a decade like Elrich and Leventhal, the public system is not built for speed. If you are a late starter, chances are you will need either traditional fundraising or self-financing to close the gap and have a chance to win.