By Adam Pagnucco.

Over the weekend, Council Member Will Jawando announced his intention to introduce a resolution “declaring racism a public health emergency in Montgomery County.” His statement on Facebook appears below.

Of course, the county already has a law designed to deal with racial disparities of all kinds: the Racial Equity Law.

What happened to it?

Work on the law began in April 2018, when the county council passed a resolution lead-sponsored by Nancy Navarro and Marc Elrich calling for “an equity policy framework in county government.” The resolution stated:

The Council is committed to examining the data needed to develop an equity policy framework that would require the County to question how budget and policy decisions impact equity.

This effort must be a partnership between the County Council, County Executive, County Government, county agencies, institutions, and our community. The County Government must challenge itself to bring new and different partners to the table. Partnering with other jurisdictions as members of the Government Alliance on Race and Equity (GARE) will also enhance the County’s effort and commitment to fostering equity.

Equity analyses should be part of capital and operating budget reviews, appropriation requests, and legislation. Program and process oversight should be undertaken viewing programs and processes through an equity lens. Equity targets and measures of progress must be put in place.

The resolution was followed by three different reports by the Office of Legislative Oversight: Racial Equity in Government Decision-Making: Lessons from the Field, Racial Equity Profile Montgomery County and Findings from 2019 Racial Equity and Social Justice Community Conversations. Navarro and Elrich held meetings in Silver Spring, Germantown, White Oak and Gaithersburg to discuss the issue that were reportedly attended by 750 people. Legislation to create an Office of Racial Equity and Social Justice and a Racial Equity and Social Justice Committee was introduced in September 2019, passed unanimously by the council in November and signed into law on December 2. The legislation was scheduled to take effect on March 2, 2020.

So what are the major provisions of the law and how is the county doing on implementing them? Let’s discuss a few.

1. The executive must appoint, and the council must confirm, a 15-member Racial Equity and Social Justice Advisory Committee that would develop and distribute information about racial equity, promote educational activities and advise the executive and council on the issue.

Status: The council’s cumulative agenda for the year does not record any nominations sent over by the executive for this committee.

2. The executive must adopt a “racial equity and social justice action plan” by Method 2 regulation that would provide for community engagement and a host of requirements and metrics for every department in county government. Under Sec. 2A-15 of the County Code, a Method 2 regulation must be sent to the council for approval or disapproval.

Status: Four different sources inside the council building reported not seeing this regulation yet. The council’s cumulative agenda has no record of it.

3. The executive must “explain how each management initiative or program that would be funded in the Executive’s annual recommended operating and capital budgets promotes racial equity and social justice.” This is a time-consuming requirement as the executive’s operating and capital budgets contain hundreds of items each.

Status: The executive’s FY21 recommended operating budget, which was released after the racial equity law took effect, contains none of this language.

4. The law requires that “racial equity and social justice impact statements” must be drafted to accompany each bill introduced at the county council. The statements are due no less than 21 days after a bill’s introduction and no less than 7 days before the bill’s hearing, although the council president may change the deadlines.

Status: As of this writing, 13 bills were introduced after the racial equity law took effect on March 2. Six of the bills were passed. None of their action packets contained racial equity and social justice impact statements. The bill specifies that the Office of Legislative Oversight (OLO), which is part of the legislative branch, is responsible for drafting the impact statements. To be fair, the part of the bill referring to the impact statements takes effect on August 1, 2020 – five months after the rest of the bill – and $119,170 was added to OLO’s budget to pay for a “Racial Equity Legislative Analyst Position.”

5. The bill creates an “Office of Racial Equity and Social Justice” to perform “equity assessments” on county policies, provide racial equity and social justice training to county employees, develop short and long term goals with metrics to redress disparities, work with departments to create the county’s “racial and social justice action plan” and staff the racial equity advisory committee.

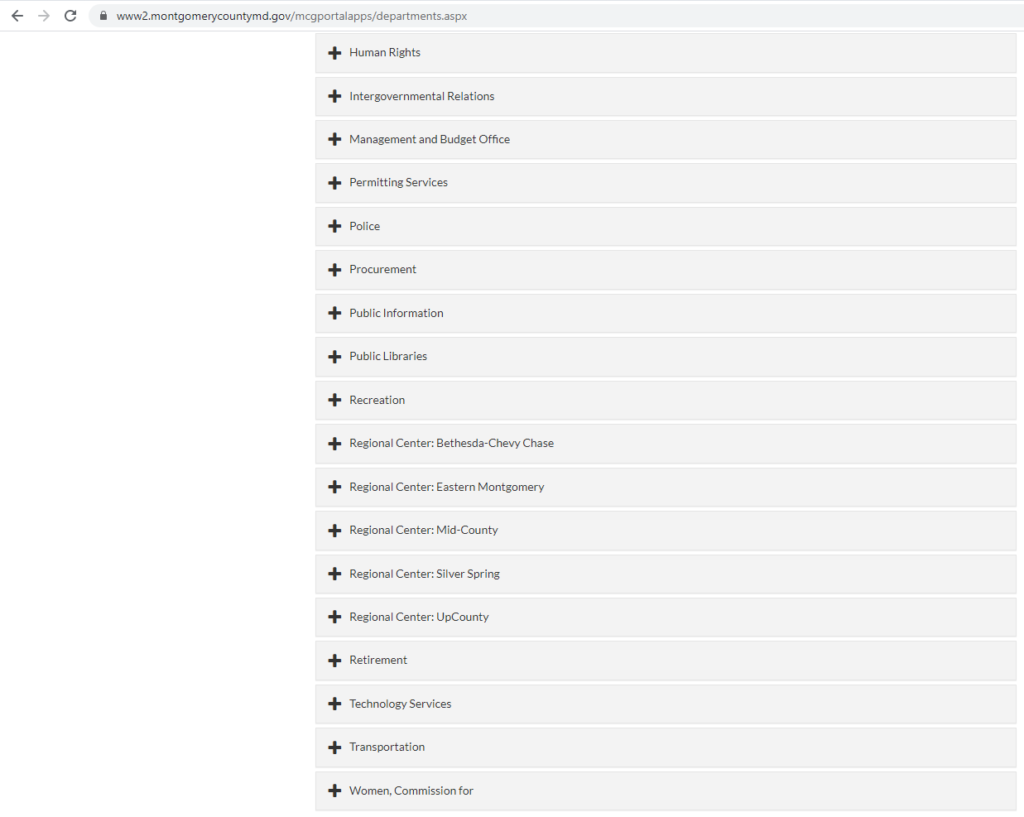

Status: Days before the law took effect, the council confirmed one of Elrich’s former council staffers as the new “Chief Equity Officer” at a salary of $150,000. The office had a budget of $584,072 in the executive’s recommended budget and includes two full-time positions plus money for operating expenses. Despite the Chief Equity Officer being on the job for three months, the racial equity office does not appear on the county’s list of departments and offices as shown below.

There are a host of other requirements in the law, such as one mandating that every department designate a “racial equity and social justice lead” to work with the racial equity office. Has that been done?

Because of its sweeping nature, the racial equity law goes beyond the bare bones of its structure in the legislation. For example, it mandates that “equity assessments” must be performed “to identify County policies and practices that must be modified to redress disparate outcomes based on race or social justice.”

One program for which that might have been helpful was the county’s grant program to small businesses affected by the COVID-19 crisis. When the county’s grant program went live on April 15 at around 3 PM, the first wave of applicants found out mainly through emails from chambers of commerce or direct notifications from council members. The county’s official blast emails announcing the grants started going out around 4:30 PM and continued into the evening. That means that the best-connected, best-informed businesses got first dibs on the grants. Did that have an impact on the demographic distribution of the grant recipients? We will never know because the grant application did not ask for the applicant’s race. Think about this: in the aftermath of the racial equity law’s passage, the county launched its biggest business assistance program ever – $25 million for more than 6,700 businesses – and the county has no apparent way to measure how much of this money went to minority business owners.

And so at this writing, the only tangible outcome from MoCo’s much-publicized racial equity law is the budgeting of roughly $700,000 in tax dollars and the creation of three full-time positions. If anything else has been accomplished after the law’s passage, there is no evidence of it.

MoCo officials have talked a lot about racial equity over the last two years. The reality is that they have a ton of work to do.