By Adam Pagnucco.

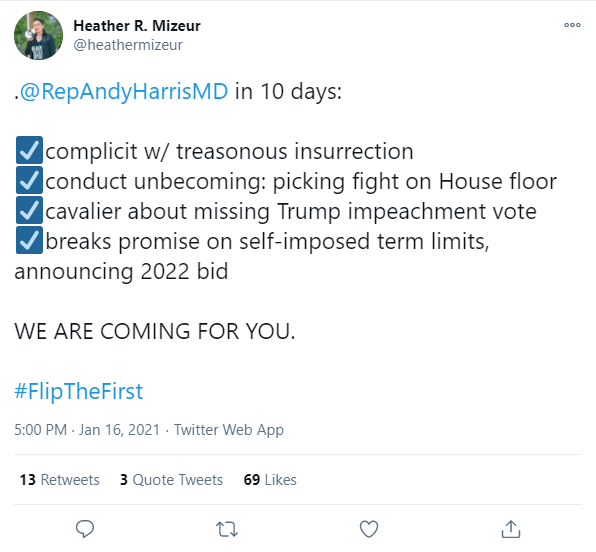

With a majority of Democratic state legislators calling on him to resign and former Delegate Heather Mizeur, now an Eastern Shore resident, announcing a run against him, District 1 GOP Congressman Andy Harris has a target on his back. Democrats all over the state are offended by his alliance with Donald Trump, his inexcusable behavior on the House floor, his failure to condemn QAnon and various other misbehaviors over the years. Now he is seeking a seventh term after pledging to serve only six. Democrats want him out but here’s the big question:

Can Andy Harris actually be defeated?

The key to answering that question lies in examining Harris’s district. Maryland’s first congressional district has historically contained the Eastern Shore. Variations in its composition have depended on which other jurisdictions have been added. In the 1970s and 1980s, the district contained Harford County and the three southern Maryland counties (Calvert, Charles and St. Mary’s). In the 1990s, it contained a large piece of Anne Arundel County and a tiny piece of Baltimore City. In the early 2000s, it contained parts of Anne Arundel, Baltimore and Harford counties. Since 2011, it has contained parts of Baltimore, Carroll and Harford counties as it has been stretched out along the Pennsylvania border.

In the 2011 redistricting round, General Assembly Democrats had two goals: fortify their congressional incumbents and flip Western Maryland’s sixth district from red to blue. They accomplished both but the price of doing so was packing Republican precincts in the Baltimore suburbs into the first district. That greatly benefited Harris, who was first elected in 2010 when he defeated a one-term Democratic incumbent. Harris has not been seriously threatened since.

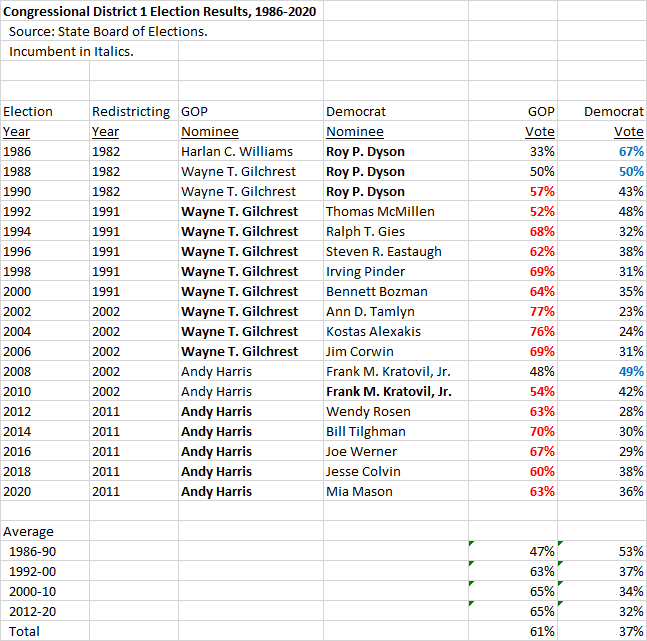

The table below shows the history of general elections in the first district since 1986.

Since Democratic incumbent Roy Dyson was defeated in 1990, the Democrats have gone an abysmal 1-15 in the district’s general elections. The sole exception was in 2008, when GOP incumbent Wayne Gilchrest was defeated by Harris in the primary and Queen Anne’s County prosecutor Frank Kratovil squeaked in during Barack Obama’s first election to the presidency. Harris defeated Kratovil two years later during the tea party revolt. It’s worth noting that in the last 30 years, only three incumbents have been defeated here: Dyson and Kratovil, both Democrats, and the Republican Gilchrest who was beaten in a primary by the more conservative Harris.

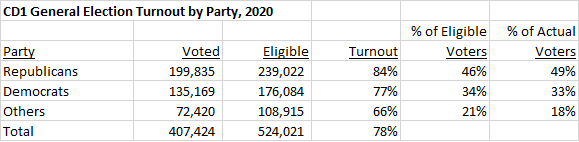

The first district is now the most heavily Republican congressional district in the state. The table below shows its turnout by party in the 2020 election. Republicans accounted for 46% of eligible voters and 49% of actual voters. Democrats accounted for 34% of eligible voters and 33% of actual voters and turned out at a lower rate than Republicans.

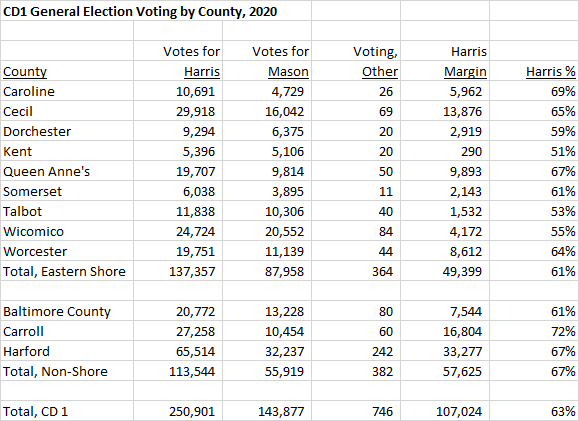

Harris won the 2020 general election with 63% of the vote, about average for his tenure as an incumbent. The table below shows the breakdown of his votes against challenger Mia Mason by county. Harris pulled a margin of nearly 50,000 votes from the Eastern Shore and almost 58,000 votes from the non-Shore counties, illustrating just how much GOP votes in the Baltimore suburbs are helping him win.

Put together the above two charts and a successful Democratic challenger would have to get votes from all the Democrats, almost all the unaffiliated voters and a smattering of Republicans. That is a LIFT.

How would the Democrats have made up the 107,000 vote margin that elected Harris last November? Getting a top-notch candidate would help; Harris had a cash on hand advantage over Mason in October of more than $1 million to roughly $2,500. Mizeur won’t have any problem raising money against Harris. She is an able politician who surprised people in the 2014 Democratic gubernatorial primary, but is the former Takoma Park progressive a good fit for the first district?

Mizeur doesn’t hold back when discussing Harris.

It’s hard to see a scenario in which the Democrats could defeat Harris without changing the district’s boundaries. Here’s where it gets difficult. Let’s suppose that the Eastern Shore remains at the heart of the district. The shore gave Harris a 50,000 vote margin last time. The Democrats would have to rearrange the rest of the district from a plus-58,000 vote margin for Harris, as it was in 2020, to a negative-51,000 vote margin. A great candidate could make up some of those votes, but this is still tough.

Where would the new precincts come from? The Democrats could draw a line across the bay bridge and up into Baltimore City. There’s a bit of precedent for that as the district contained a handful of city precincts in the 1990s. But the number of precincts would have to be far greater than a handful to overturn Harris’s advantage on the shore. And this would create a truly odd district, combining inner city Baltimore with some of the most rural areas in Maryland.

The Democrats could also add left-leaning precincts around Annapolis and in Howard County but would it be enough? If they added in Southern Maryland, as it was in the 1970s and 1980s, it’s not clear that the district would be much bluer.

Complicating the issue is the effect of altering the first district on other nearby districts. While Harris is protected by keeping Republicans in his district, Democratic incumbents in the second, third, seventh and eighth districts are protected by keeping Republicans out. What will they say if they are told to swap their blue precincts with Harris’s red precincts? I might speculate but this blog prohibits profanity!

Getting rid of Harris will require a historically great opponent, an investment of huge financial resources and redistricting changes that will generate resistance with no guarantee of success. Additionally, the Democrats could get lucky if a primary challenge from a credible candidate like Harford County Executive Barry Glassman drains some of Harris’s war chest. Nothing is impossible in politics. But this is a BIG mountain to climb. Let’s see just how badly the Democrats want Harris out of Congress.