By Adam Pagnucco.

Bill 13-22, commonly called “the electrocution bill,” is swiftly advancing in the county council. The bill has an interesting history. It was jointly authored by County Executive Marc Elrich and Council Member Hans Riemer and introduced in June. At that time, Elrich and Riemer were running in the primary against David Blair, who had been endorsed by the Sierra Club – an event that infuriated Blair’s opponents. (I was Blair’s campaign strategist at the time.) The bill had a hearing right after the primary and was in committee in October and earlier this month. After many amendments, it will be discussed at the full council tomorrow.

The intention of the bill is to mandate that most future buildings do not rely on natural gas and instead use the electric grid to encourage the use of clean energy. (The original version of the bill also included additions and major renovations but those have been removed.) The environmental benefits are quite modest since over the last year, 92% of the regional grid’s energy has been powered by gas, coal, nuclear and petroleum while less than 7% has come from wind, solar and hydro. (You can check it here.) The costs are staggering, if unknown. The bill’s economic impact statement may be the most negative I have ever seen on county legislation but council analysts were unable to come up with a price tag. That means the council has no idea what it will cost businesses, tenants, residents and ratepayers.

Three recent data points provide a hint.

First, electrification increases use of the electric grid. MCPS was widely praised for buying more than 300 electric buses this fall. That would eliminate tons of diesel fumes but it comes at a cost: the Washington Post reported that the depot where they are housed now requires as much electricity as “10 big hospitals.” That depot is not far from Westfield Montgomery mall, where more than 700 new residential units have been approved. Can the electric grid in that area handle all of that new demand?

Second, this leads us to consider electrification’s financial impact on energy infrastructure. BGE released an “Integrated Decarbonization Strategy” last month that studied how much upgrades required by electrification would cost. The scope of cost included “electric generating capacity, electric transmission and distribution, customer capital costs, renewable and fossil fuels costs and costs of gas and networked geothermal infrastructure.” The study evaluated three scenarios.

1. Limited gas: “High electrification and shift away from delivered gas and other fuels.” Buildings and industry would be subject to “efficiency and electrification.” Cost: $52 billion.

2. Hybrid: “Leverages an increasingly clean electric system, high electrification and the gas network.” Buildings would be subject to “efficiency, electrification, gas-electric hybrids and a targeted role for alternative fuels.” Industry would be subject to “efficiency, electrification and alternative fuels.” Cost $38 billion.

3. Diverse: “Leverages an increasingly clean electric system, high electrification and the gas network.” Buildings would be subject to “efficiency, electrification, gas-electric hybrids, gas heat pumps, network geothermal and alternative fuels.” Industry would be subject to “efficiency, electrification and alternative fuels.” Cost $40 billion.

Now it’s time for caveats. It’s not clear that BGE studied exactly what the electrocution bill as amended now proposes. Also, BGE’s service territory has roughly four times the customers as Pepco’s service territory in Montgomery County.

But the order of magnitude is instructive. We are not talking about thousands of dollars in costs or even millions of dollars. We are talking about billions, folks. With a B. And pluralized.

All of those billions will be paid by ratepayers. (Don’t think for one second that Pepco will eat them!) What are the implications of massive increases in electric bills for seniors on fixed income? Or small businesses? What are the implications for racial equity?

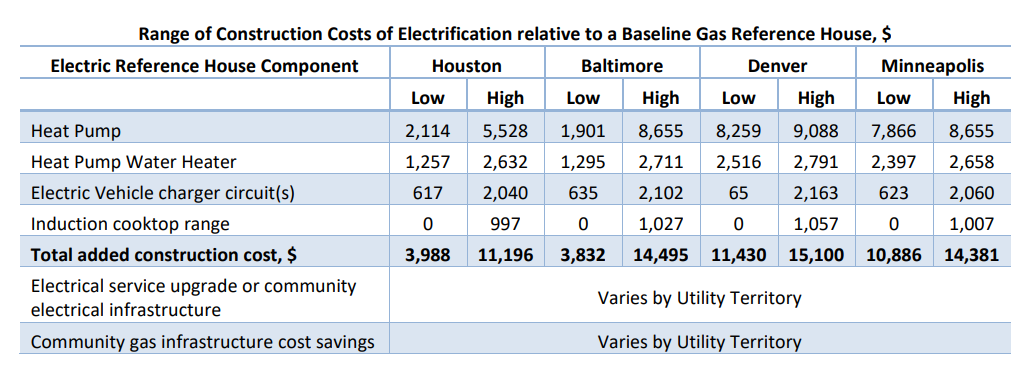

Third, electrification will impact housing construction costs and utility bills. The National Association of Homebuilders commissioned a study last year that examined the potential costs and benefits of electrification in four markets: Houston, Baltimore, Denver and Minneapolis. The study found that effects varied depending on climate conditions in local areas, but Baltimore is a good proxy for Montgomery County. In terms of construction costs, the study found that electrification in Baltimore would add between $3,832 and $14,495 to the cost of a new home.

What about annual utility bills? The study says this:

In the mixed climate (Baltimore), the annual energy use cost for the electric house with a high efficiency heat pump and 80-gallon heat pump water heater (3.75 UEF) ranges from a savings of $77 (18 SEER/9.3 HSPF 2-stage heat pump) to $184 (19 SEER/10 HSPF inverter heat pump) compared to a gas baseline house, with simple payback of 44 years to 60 years; however, when compared to a gas house with high efficiency gas equipment, the consumer is again faced with higher upfront construction cost and higher energy use cost.

So utility bills might cost more or they might cost less. In the best case scenario, a homebuyer might break even in 44 to 60 years. How many people own one house for that long?

Given the council’s recent actions on housing, it boggles the mind why they would want to add $4,000 to $14,000 onto the cost of new housing. What was all the ruckus around Thrive 2050 about? What are the racial equity implications for home ownership with extra price increases of that magnitude?

Look folks, the future of our society is not one of continued reliance on fossil fuels. (The council should have recognized that when they banned solar panels in the overwhelming acreage of the agricultural reserve.) But this bill needs a LOT of work. Any increase in renewable energy use it delivers is slight and it does nothing to build renewable energy capacity. In return for such small benefits, it contains unfathomable costs. Additionally, there are many serious aspects to this legislation involving implementation, economic competitiveness, costs on county-owned building projects, the role of the state, equity, possible assistance to impacted groups and much more. Some on the council think they can figure this out in a couple weeks before the new council term begins. News flash: they don’t have the time, the expertise or the data to do so.

This whole episode brings back memories of the so-called “Diggs Council,” a 1966 county council full of lame ducks headed by Council President Kathryn E. Diggs. That council pushed through mass upzoning throughout the county shortly before they headed out the door, provoking widespread outrage and later efforts to overturn their work. This council should not emulate their example by costing residents and businesses billions of dollars days before they leave office.

And so the current county council has a choice. They can leave on a high note having saved the planning board from destruction, having passed Thrive 2050 and having shut out the Republican Party at election time. Or they can short circuit their success by condemning the county’s economy to the electric chair.