By Adam Pagnucco.

One of the hottest issues for students of elections right now is ranked choice voting (RCV). While RCV has been around for decades, it is spreading quickly through the United States. Maine and Alaska have applied it to many of their elections and dozens of municipalities use it too. Serious discussions are underway as to whether it should be used in Maryland. (Takoma Park has used it since 2007.)

So what is RCV? Traditional elections allow voters to express their first choice only, or in multiple seat elections, only as many choices as there are seats. RCV allows voters to express not only their first choice but also more choices in case their first choice does not win. By tallying next choices for candidates who are eliminated, surviving candidates accrue more votes until one (or more if there are multiple seats) gets enough votes to win.

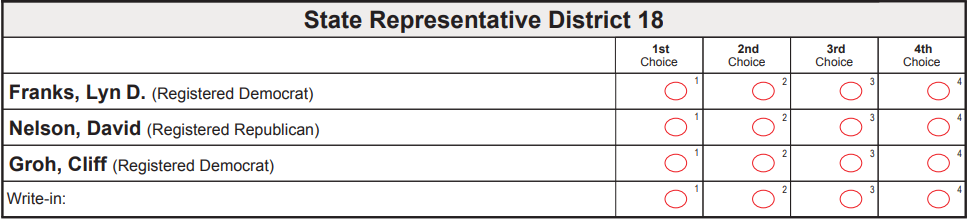

Let’s illustrate how RCV works with an example from a state legislative race in Alaska. In the 2022 general election, three candidates ran in House District 18: Republican David Nelson and Democrats Cliff Groh and Lyn Franks. (Alaska allows up to four candidates who emerge from the primary to run in the general election regardless of their party.) Nelson was an incumbent but this district was redrawn, thereby eroding his incumbent advantage. The image below shows what the ballot for this race looked like. See how voters can express their choices? Even write-in voters can do so.

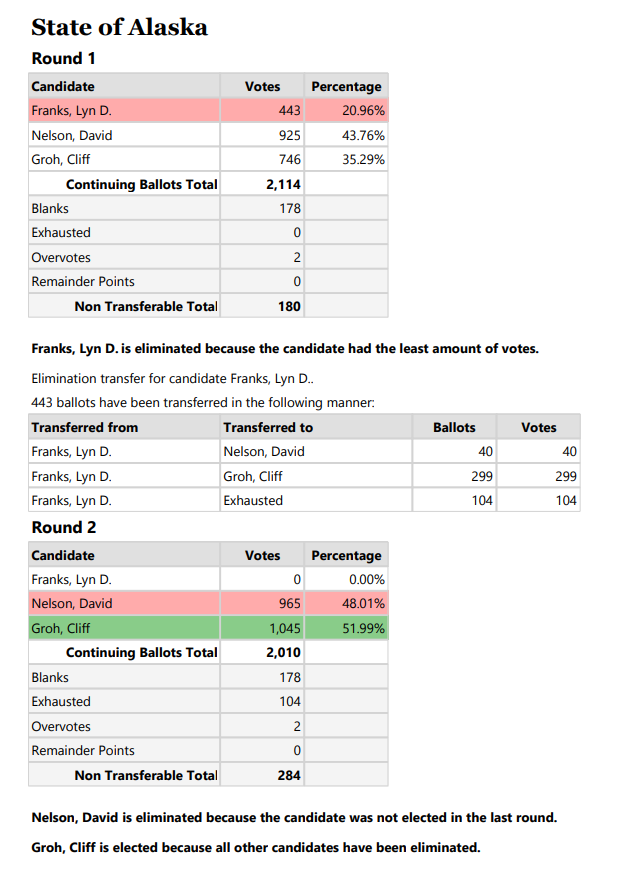

In the first round, Nelson earned 925 votes, Groh received 746 and Franks received 443. In a traditional election, Nelson would have won.

But this is RCV, so the election is not necessarily over after the first count. Franks was eliminated and the second choices of her voters were counted. Of Franks’s 443 voters, 299 picked Groh as their second choice, 40 picked Nelson and 104 did not pick a second choice. The new tally was now 1,045 for Groh and 965 for Nelson. Under RCV, Groh and not Nelson was elected. Additionally, this example shows how RCV flipped a Republican win to a Democratic win, although Alaska’s top four system is unusual. The RCV tally from Alaska’s board of elections appears below.

RCV supporters are very dedicated to this concept. Here is how Fair Vote, which is advocating for RCV across the country, makes a case for it.

Our “choose-one” elections deprive voters of meaningful choices, create increasingly toxic campaign cycles, advance candidates who lack broad support and leave voters feeling like our voices are not heard.

Ranked choice voting (RCV) — also known as instant runoff voting (IRV) — improves fairness in elections by allowing voters to rank candidates in order of preference.

RCV is straightforward: Voters have the option to rank candidates in order of preference: first, second, third and so forth. Votes that do not help voters’ top choices win count for their next choice.

It works in all types of elections and supports more representative outcomes.

I will admit that the prospect of ranking additional choices in case my first choice candidate loses is both attractive and fun. But until I started drafting this series, I had no position on RCV because I did not know exactly what outcomes it produces. Before favoring or opposing something, shouldn’t we have some idea of what that something actually does?

Well, now I do. It took me a long time but I have assembled a database of more than 1,100 actual RCV-eligible elections from all over the country, including many from the 2022 general election. As this series proceeds, you will see exactly what this data says and then you can make up your own mind about whether you support RCV. Critical thinking works, folks!

On to Part Two soon.