By Adam Pagnucco.

Ranked choice voting (RCV) allows voters to rank candidates according to their preference of choice. And as candidates are eliminated, their voters’ next ranked choices are counted until the winner crosses the threshold of victory. Part One examined an example from Alaska in which RCV flipped a state legislative election from a Republican win to a Democratic win.

But let’s not believe that the example from Alaska is typical of how RCV elections actually work. To measure that, I assembled a dataset of every RCV-eligible election I could find – more than a thousand of them – over the last two decades. These are not all of the RCV elections ever held in the United States. Cambridge, Massachusetts has been using RCV since the 1940s. But I bet that this dataset accounts for the overwhelming majority of recent RCV elections in our country.

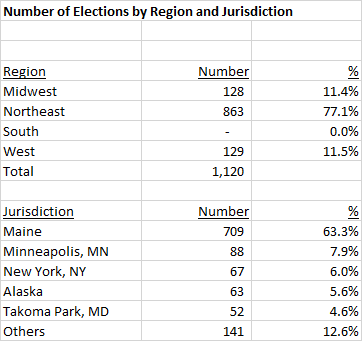

The table below shows the distribution of RCV-eligible elections by region and jurisdiction.

The northeast and specifically Maine dominates the dataset. Maine voters approved RCV in 2016 and it survived multiple legal challenges. The state’s Bureau of Corporations, Elections and Commissions explains that Maine uses RCV “for all of Maine’s state-level primary elections, and in general elections ONLY for federal offices, including the office of U.S. President. The ranked-choice rounds are used only in races in which there are more than two candidates.” Maine has 186 state legislative seats and its primaries in 2020 and 2022 had RCV as an option. That’s why it has by far the most elections in the dataset. Overall, the dataset contains elections from 29 different jurisdictions, 27 of which are municipalities. The latter mostly had non-partisan elections.

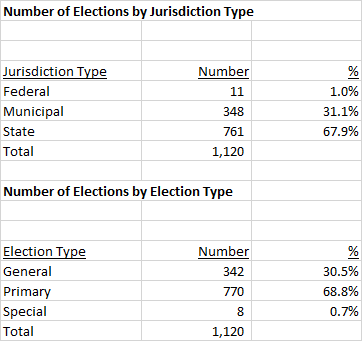

The table below shows the distribution of RCV-eligible elections by jurisdiction type and election type.

Federal elections covered by RCV are rare. The only ones in the dataset are from Alaska and Maine. (Alaska’s 2022 elections for U.S. Senate and U.S. House have received substantial press coverage.) Among RCV-eligible elections, state offices outnumber municipal offices 2-to-1 (mostly because of Maine) and primaries outnumber generals by more than 2-to-1 (again because of Maine).

Two more quick facts about the sample. 84% of the elections are from 2020 or later – you guessed it, because of Maine. And in partisan primaries, 52% were Democratic primaries and 47% were Republican primaries.

Now let’s define the term “RCV-eligible.” Just because an election might qualify for RCV does not mean that it will actually use RCV. There are certain circumstances in which an RCV election will function exactly as a traditional election would, including:

1. A candidate is unopposed.

2. The number of candidates exceeds the number of seats at play by one. For example, if two candidates are running in a one-seat race, ranked choice has no role.

3. A candidate exceeds the required threshold for victory in the first round. For example, in a multi-candidate race for one seat, a candidate exceeds 50% in round 1. This happened in the 2022 primary for Montgomery County State’s Attorney. Some jurisdictions may choose to tabulate ranked choices anyway in such circumstances but they will not change the outcome.

As it turns out, these three categories account for 85% of the elections in our dataset. In other words, 85% of RCV elections do not actually use ranked choice because they don’t have enough candidates to trigger it or one candidate wins outright in the first round. This has a huge impact on whether RCV actually delivers different outcomes than traditional elections because the vast majority of RCV elections ARE traditional elections.

We will have more in Part Three.