By Adam Pagnucco.

Part One gave an example of how ranked choice voting (RCV) works and Part Two described our dataset of more than 1,000 RCV-eligible elections from across the country. Especially notable is that more than 60% of RCV elections over the last 20 years have been in Maine, which uses them for its state legislative primaries. But that’s changing because RCV is spreading around the U.S., mostly in municipalities.

Now let’s proceed to the key question: do RCV elections produce different outcomes than traditional elections?

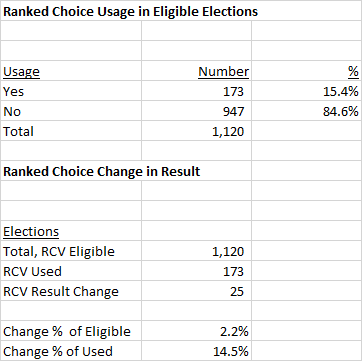

The table below shows three important numbers from our dataset. First, the number of elections in which RCV was an option (1,120). Second, the number of elections in which RCV was actually used (173). And third, the number of elections in which the winner(s) in RCV were different than the winner(s) of the first round (25).

The first thing that stands out is that RCV was actually used in just 15% of the elections in which it could have been used. That’s because 85% of the elections had an unopposed candidate, an insufficient number of candidates to trigger ranked choice or a candidate who crossed the winning threshold (like an absolute majority) in the first round. This is a critical finding: RCV usually does not produce different results than traditional elections because 85% of the time, they ARE traditional elections.

Second, in elections in which ranked choice is actually used, the winner(s) differ from the first round just 15% of the time.

And finally, counting all elections in which ranked choice is an option, RCV produces a different result just 2% of the time. That’s right, TWO PERCENT.

Maryland has one jurisdiction that has used RCV: Takoma Park, which adopted the system in 2007. Since then, Takoma Park has had 52 elections in which RCV could have been used. Only 6 of them actually used RCV and none of them produced a different result than a traditional election.

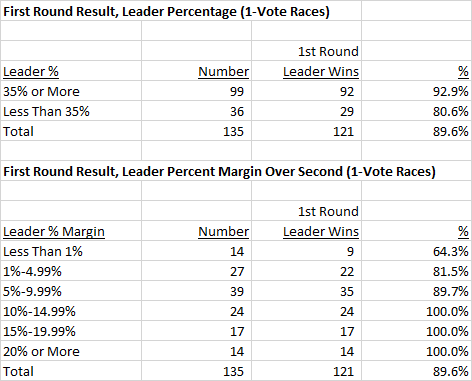

When is RCV most likely to produce a different result? The table below shows the results of 135 races using RCV with one winner (excluding multi-seat races) in different ranges of performance for first round leaders.

Two observations hold. First, when the first round leader receives more than 35% of the first round vote, that person is more likely to win than first round leaders with weaker performances. And second, first round leaders with large percentage margins over the candidate in second place are more likely to win than those with small margins. This makes sense – strong candidates tend to win under most systems.

There is one place where RCV regularly produces different results than traditional elections: Cambridge, Massachusetts. In 21 RCV-eligible elections in Cambridge since 2001, ranked choice was used every single time and it produced different results than the first round on ten occasions. That 48% rate of change in result was a big outlier in the dataset.

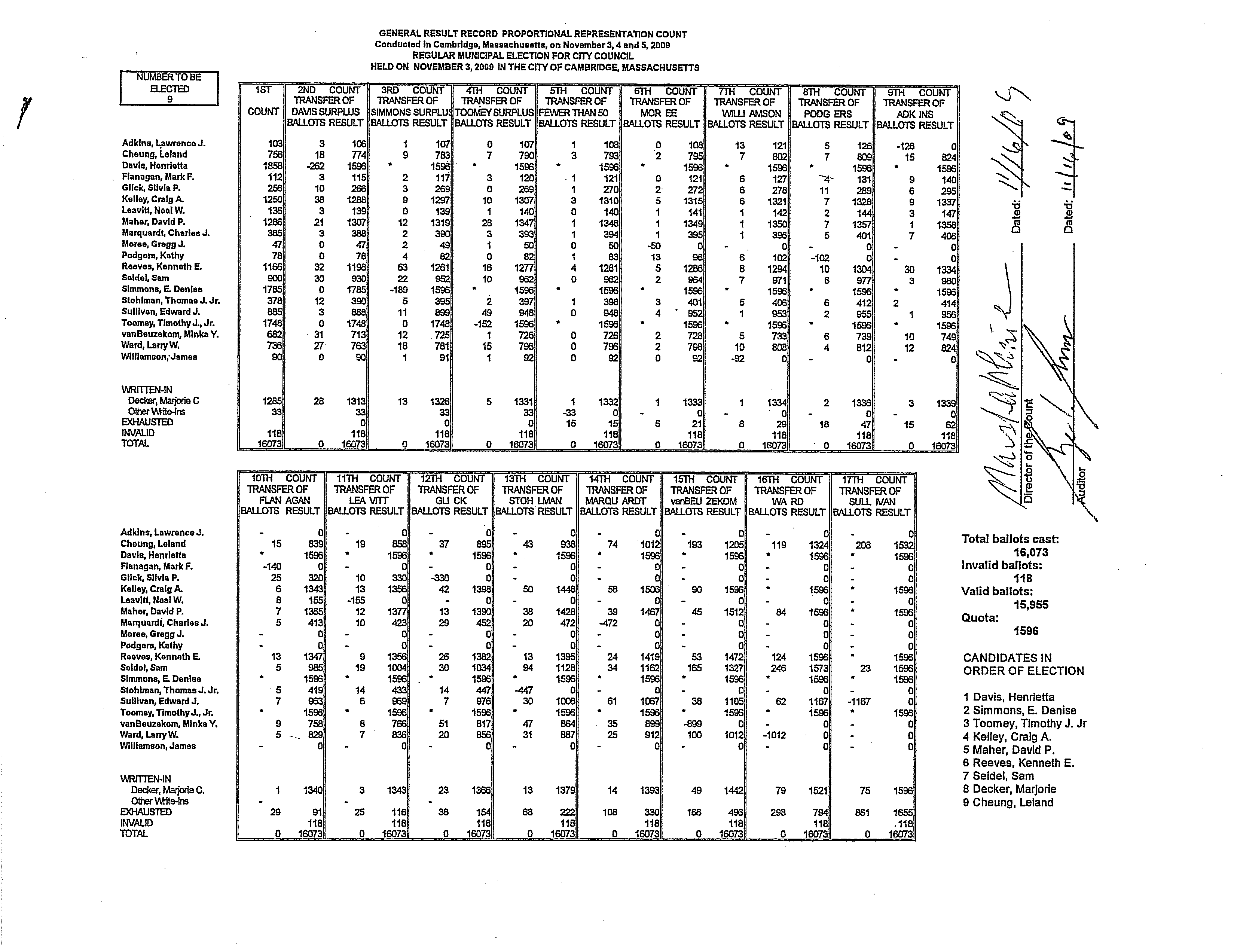

But there’s a reason for that – Cambridge’s elections are very unusual. The city has two types of elections every two years – city council and school committee. In city council elections, the top nine candidates win. In school committee elections, the top six candidates win. This produces some divergent outcomes as RCV in Cambridge shifts vote totals often.

The graphic below is from Cambridge’s 2009 city council race, which featured twenty filed candidates plus one write-in candidate vying for nine seats. Assuming that one can even read the results (I struggled to do it!), see how they vary across the 17 counts. I don’t know of any elections in Maryland that function like this, in part because I don’t know of any in which nine at-large candidates are elected all together in the same race.

Finally, for progressives who hope that RCV will produce gains for them, I see no evidence for that view in the dataset. I found only four general elections that produced a shift in the party who won, and in those elections, Democrats and Republicans each benefited twice.

So we have now established that RCV seldom changes outcomes when compared to traditional elections. I will conclude with a few more issues to consider in Part Four.