By Adam Pagnucco.

Part Three explained how MCPS transfers teacher salary money towards other spending almost every year. And that’s not just on MCPS – the county council has approved these diversions in 15 of the last 18 fiscal years. That’s not the only place where teacher salary money winds up. There is an arguably larger destination for this money aside from the wallets of teachers.

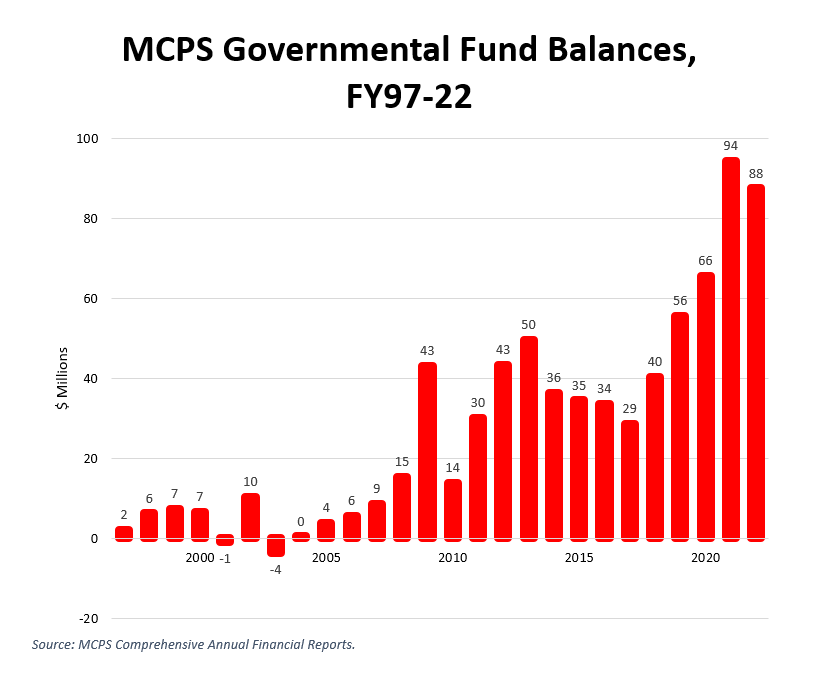

Like most governmental entities, MCPS has a fund balance, which is sound fiscal policy. Many unexpected expenditures can occur during a school year – weather events, spikes in benefit costs, legal settlements and much more. Without a fund balance, MCPS would have to make regular supplemental funding requests to the county council, and elected officials usually do not enjoy these kinds of surprises. So the school system regularly holds money in reserve and carries some of it over to each year’s new budget. That money has been rising dramatically.

MCPS’s comprehensive annual financial reports (CAFRs) report on its governmental fund balances. The chart below shows those amounts from FY97 through FY22.

Twenty years ago, MCPS had very low fund balances and even went negative in FY01 and FY03. Starting around FY11, MCPS had fund balances regularly exceeding $30 million, which were probably prudent amounts. But after FY17 – the last time the county raised taxes and said it was for schools – MCPS’s fund balance began to soar. In FY21 – the first full year of the pandemic – it hit $94 million. As we saw in Part Three, that was the same year that MCPS transferred $63 million in instructional salaries to other purposes – mainly instructional supplies and employee benefits – as part of its response to the pandemic.

There is one caveat to bear in mind – not all of MCPS’s fund balance is liquid. Depending on the year, $6 to $9 million of it is non-spendable, chiefly because it is contained in inventories. And a few hundred thousand dollars are restricted to specific purposes. Even with that value removed, MCPS still had an $80 million fund balance in FY22.

Here is the proof – ten years of MCPS fund balances from its FY22 CAFR, page 117.

Why has MCPS’s fund balance been soaring? There are bound to be many reasons for this, but let’s consider an important one – MCPS’s longstanding practice of not spending all of its budgeted instructional salaries, which we explained in Part Two.

The chart below shows MCPS governmental fund balances (in red) and the gap between final budgeted and actual instructional salaries (in green) from FY04 through FY22.

Both of these values began to take off after FY17. Instructional salaries is the largest single component of MCPS’s operating budget. The system’s variance between budgeted and actual spending on salaries has been growing. It’s reasonable to ask whether there is a relationship between rising fund balance and the rising gap between budgeted and actual spending on teacher salaries.

Now let’s look at this from MCPS’s point of view. It’s apparent from the system’s recent comprehensive annual financial reports that MCPS did not receive all of the federal revenues assumed in its final budgets. That’s outside MCPS’s control. Then there was the pandemic, which caused enormous stress in the teaching profession. Schools all over the country are starving for teachers. MCPS may not be able to spend all of its budgeted salary money even if it wants to. That’s why school system management should collaborate with its unions – especially the teachers union – to design attractive recruitment and retention packages. But instead of collaboration, the labor-management relationship has deteriorated into regular conflict.

I am not assigning exclusive blame to MCPS management or the unions for this. I worked in the labor movement early in my career and have had many labor clients since. Outsiders can’t see what goes on at the bargaining table and behind closed doors. In any case, having money budgeted for salaries winding up in fund balance or other spending is a sub-optimal outcome. And it certainly does not inspire public confidence in a ten percent property tax hike. MCPS must get its house in order and its overseers – the county executive, the county council and the school board – must help make that happen.

We will conclude with a look back at the last time a tax hike was sold as being for public schools.