By Adam Pagnucco.

Recently, an unusual dispute broke out between a top state official and local officials over the subject of juvenile crime. Vincent Schiraldi, secretary of the Maryland Department of Juvenile Services (DJS), claims juvenile crime is in long-term decline. Other officials have pushed back and expressed concern about some increases in specific juvenile crimes.

Who is right and what is happening in MoCo?

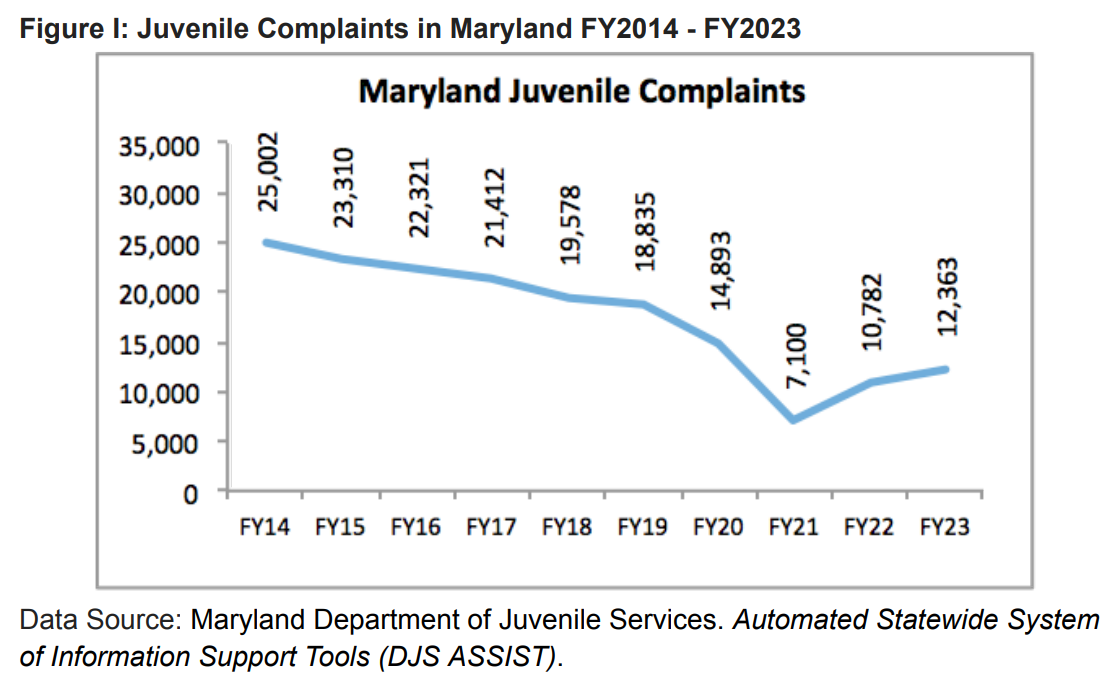

Schiraldi went first. Last month, DJS released a report showing a drop-off in overall statewide juvenile crime. The report included the chart below showing juvenile complaints, defined as “all juvenile arrests referred to DJS, as well as citizen, school, and Children In Need of Supervision (CINS) complaints referred to DJS,” from FY14 through FY23.

Schiraldi then wrote a commentary in the Baltimore Sun asserting that “Many of the assumptions that society seems to hold about youth violence are wrong.” Specifically, Schiraldi contended that juvenile crime is a small proportion of total crime, juveniles are more likely to be victims than perpetrators, and incarceration is not the most effective way to combat juvenile crime.

This drew pushback from a number of state legislators who hear regular constituent complaints about crime, both juvenile and otherwise. Also joining in were local prosecutors. The Post carried this quote from Montgomery County State’s Attorney John McCarthy:

Montgomery County State’s Attorney John McCarthy said the number of juvenile arrests nearly doubled in his county between 2021 and 2022, led by an “explosion” in carjackings, which jumped 85 percent, and handgun violations, which rose 220 percent.

“There are not adequate programs in the juvenile justice system,” McCarthy said, agreeing with public defenders who also called for additional services to juveniles in the system during the meeting. “We’re just churning kids, we’re not solving problems. We’re not rehabilitating kids, which is the goal of everyone on this call.”

McCarthy said it was a “disgrace” that a drug and alcohol residential treatment facility for juveniles does not exist in Maryland.

The Post also reported these comments from Prince George’s County State’s Attorney Aisha Braveboy.

“The concerning part for us is the categories of youth crime that are up, which includes handgun crimes, carjackings, and auto theft,” said Prince George’s County State’s Attorney Aisha Braveboy (D), who was briefed on the data late last week. “I think those are the areas that we need to focus on to impact juvenile crime, guns in particular.”

She said the “ease and access to weapons, including ghost guns and regular handguns,” are part of what propels young people to commit violent crimes. Youths being victims of crime has also increased, according to the report.

Braveboy said her office is focused on expanding Maryland’s gang statute to address crimes committed by youths because in far too many cases, she said, adults are supplying guns to young people and benefiting from the violence.

I asked McCarthy to back up his remarks and he supplied a trove of data on juvenile arrests recently offered by Montgomery County Police Chief Marcus Jones. I then discussed the data with representatives of MCPD. The full presentation can be downloaded at the end of this column. Here are three things that struck me.

Some juvenile arrests are way up and others are way down.

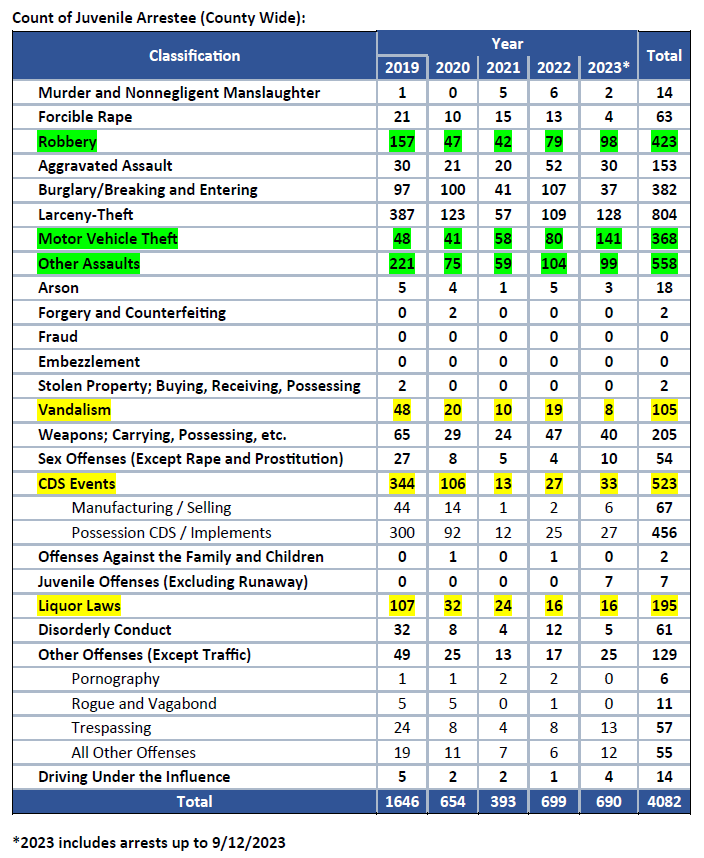

The chart below shows various categories of juvenile arrests from 2019 through 9/12/23. Some categories have climbed steeply since the pandemic with motor vehicle thefts exploding. Many other categories are down as well as the overall total.

What explains the sharp divergence in trends of certain kinds of crime? My sources point to the passage of the state’s Juvenile Justice Reform Act of 2022, which eliminated criminal charges for children under the age of 10 and eliminated non-violent charges for children aged 10-12. Another new law which may be relevant is the Child Interrogation Protection Act of 2022, which imposed restrictions on police interrogations of juveniles. So some declines in less serious offenses are due to changes in state law rather than underlying behaviors, a critical fact that Schiraldi chose not to emphasize.

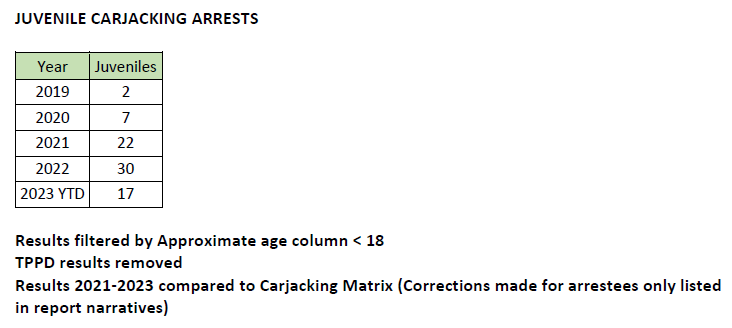

Juvenile carjacking arrests have dramatically increased but are still relatively small.

This chart shows juvenile carjacking arrests from 2019 through 9/12/23.

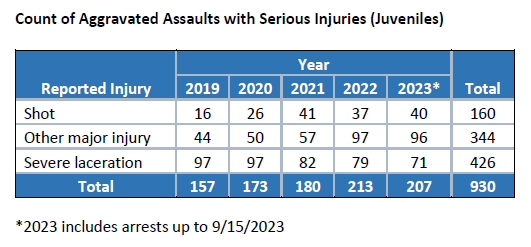

Juvenile aggravated assaults with serious injuries are up.

This chart shows juvenile aggravated assaults with serious injuries from 2019 through 9/15/23. In Maryland, first degree assaults include assaults using firearms or strangling and others that “intentionally cause or attempt to cause serious physical injury to another.”

So what should we make of this? It’s possible that Schiraldi, the state legislators and the prosecutors could all be right about some things at the same time. Overall juvenile crime could be less than it was a decade ago with the powerful caveat that state definitions of some juvenile crimes have changed. At the same time, some serious juvenile crimes appear to be rising, particularly when compared with the lockdown conditions of the pandemic. And there could be local variations in these trends, both between and inside counties.

Whatever the issues, criminal law is largely the province of the state. County public safety authorities, prosecutors and courts will deal with crime as best they can but it’s the General Assembly that establishes the parameters in which they operate.

*****

The data offered by Chief Jones appears in the download link below. The information at the bottom of page one is affected by a data system transition in December 2022, making a comparison of numbers between 2022 and 2023 impossible. MCPD informed me that that issue did not affect the data on pages two and three, from which I extracted the charts above.