By Adam Pagnucco.

In 2004, then-County Executive Doug Duncan had the county council pass a law prohibiting disruptive behavior at public facilities. One provision of the law requires the chief administrative officer (CAO) to report annually to the council on disruptive behavior orders by department. The current CAO, Rich Madaleno, recently issued a report for 2023 and that data, along with data from July 2019 on, is stored on the county’s open data website. And one fact jumps out from that data:

Disruptive behavior is overwhelmingly concentrated in the county’s libraries.

First, a bit of detail on the law itself. Sec. 32-19C of the county code mandates that:

A person must not:

(1) act in a manner that a reasonable person would find disrupts the normal functions being carried on at that public facility; or

(2) engage in conduct that is specifically prohibited by a notice conspicuously posted at that public facility. The type of conduct that may be prohibited by a conspicuously posted notice is conduct that is likely to disrupt others’ use of the public facility, or conduct that poses a danger to the person engaging in the conduct or to others.

If such conduct occurs, an “enforcement agent” – specified as “a police officer, deputy sheriff, or County security officer,” a department director, or a designee of a department director – is empowered to issue a written order providing for a number of access restrictions on the offender, including and up to denial of access for 90 days. Such orders are called disruptive behavior orders (DBOs) and are contained in the CAO’s annual reports.

The latest report, which can be downloaded below, lists 108 DBOs by department and location. Of those, 104 were issued in libraries.

The county’s open data website contains records of 290 DBOs issued since July 2019. Of those, 264 were issued in libraries, or 91% of the total. The only other department to crack more than 10 was the recreation department, which issued 13 orders over the period.

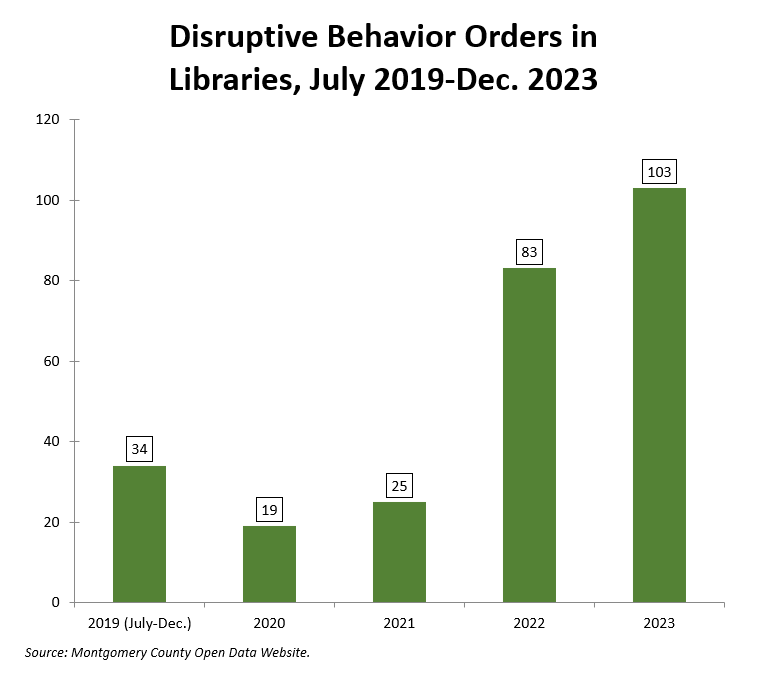

The chart below shows DBOs by year in the libraries.

Now this chart is a bit deceptive. Library buildings were physically closed due to the pandemic starting in July 2020 and did not fully reopen until July 2021. But if 34 DBOs in the half year of 2019 is compared to DBOs in 2022 (83) and 2023 (103), the trend is clearly upwards.

DBOs are not evenly distributed between libraries. Only five of them recorded more than 20 DBOs over the period. They are:

Brigadier General Charles E. McGee Library (Silver Spring): 67

Rockville Memorial Library: 54

Connie Morella Library (Bethesda): 27

Germantown Library: 26

Wheaton Library: 25 (includes co-located recreation facilities)

It’s unclear how serious these incidents were. Were they just people making noise? Or were there incidents of threatening or violent behavior? The data does not say, but of the library DBOs, 150 (56%) lasted the full 90 days allowed by county law.

At the present pace, a disruptive incident serious enough to warrant a written disruptive behavior order occurs in county libraries more than once every four days. That’s a more brisk pace than in the second half of 2019, when they occurred roughly once every six days. If this trend accelerates, the county may wish to review its security arrangements in at least some of its libraries.