By Adam Pagnucco.

MoCo voters do not love property tax hikes and they have voted several times to limit them. Under a ballot measure passed by the 2020 general electorate, the county’s charter requires a unanimous vote by the county council to raise the county’s property tax rate. Dissatisfied with the rigorous nature of this requirement, Council Members Sidney Katz and Gabe Albornoz would like to replace this limit with a two-thirds vote instead.

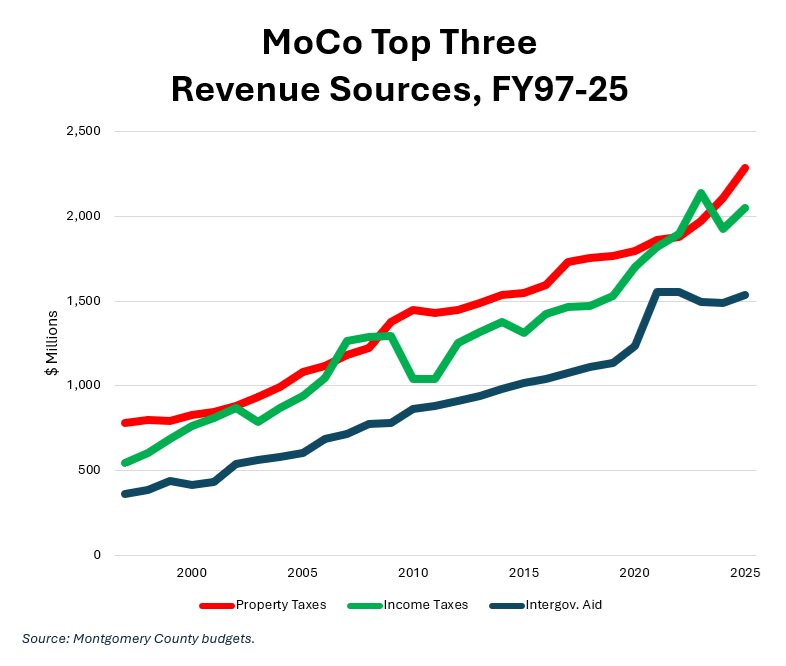

Property taxes are usually the single largest component of total revenues. The chart below shows receipts collected by the county’s top three revenue streams – property taxes, income taxes and intergovernmental aid – from FY97 through FY25. All data is actual except for FY24 and FY25, which come from approved county budgets.

Making property tax hikes easier is a big deal, both for the county budget and for the wallets of voters. As you may imagine, I have some opinions about that. But first, property taxes are complicated and our county has a long history of limiting them. Let’s start with a brief recounting of that history before we proceed with any opinions on the Katz-Albornoz proposal.

In 1978, Prince George’s County voters passed the TRIM (Tax Reform Intitiative by Marylanders) amendment, which froze the county’s ability to raise property taxes. Montgomery County had its own TRIM amendment, which narrowly failed at the ballot box. That set the twin counties on very different paths in coming decades.

Montgomery County finally passed a charter limit on property taxes in 1990. The limit was a compromise between grass-roots leaders and some members of the county council. Anti-tax activist Robin Ficker unsuccessfully tried to blow it up in court but voters passed it into law. The 1990 charter limit allowed property tax collections to grow at the rate of inflation, with some exceptions, and required 7 of 9 council members to override it.

In the early 2000s, the council voted to override the charter limit three years in a row (FY03-05). Ficker responded with a 2004 charter amendment that would have prohibited the council from overriding the limit, but it failed by a wide margin. However, in 2008, the council broke the charter limit again and Ficker was able to pass another amendment that required 9 council members to override by a hair. Voters approved a council-sponsored amendment that required a unanimous vote of all sitting council members to override in 2018, which was designed to avoid the consequences of a vacant council seat.

In 2020, Ficker tried again to eliminate the council’s ability to override the limit with yet another charter amendment. Council Member Andrew Friedson responded with a competing amendment that retained the unanimous override requirement but changed the structure of the charter limit. Under Friedson’s amendment, the limit applied to the property tax rate and not to the volume of collections. Backed by a huge coalition of progressive groups and financed by David Blair, Friedson’s amendment passed and Ficker’s amendment failed. Friedson’s charter limit now exists in current law.

County charters do not exist in a vacuum. Among other things, they can be preempted by state law – and in the case of charter limits on property taxes, they are. In March 2023, I wrote a post titled The Hand of the King that discussed a loophole in state law and the role of then-State Senator and current MoCo Chief Administrative Officer Rich Madaleno in placing it there. During the Great Recession, several counties – including MoCo – ran afoul of state law in funding their school systems below state-mandated minimums. So the General Assembly tightened school funding requirements but also provided that counties could exceed their charter limits to meet them. This had the effect of nullifying charter limits on taxes, at least when it comes to school funding. And since money is fungible, a tax loophole freeing up money for schools allows counties to move money towards other functions as well.

Bear in mind the above history when you read Part Two, which is soon to come.