By Adam Pagnucco.

Two years ago, Montgomery County passed legislation establishing building energy performance standards. Last year, the county passed legislation establishing rent control. Now, those laws are working at cross purposes, pitting two progressive priorities against each other. With regulations on one now established and the other pending before the county council, a collision is imminent.

Let’s start with building energy performance standards, known as BEPS. The bill passed in 2022 requires energy performance standards to be established by regulation for commercial and multifamily residential buildings with 25,000 or more square feet. County-owned buildings of 50,000 or more square feet are also covered. Covered buildings fall into one of six groups, each of which has different deadlines for compliance. Benchmarking, reporting and eventual compliance with performance targets are phased in for all covered buildings under regulations submitted by the county executive to the county council.

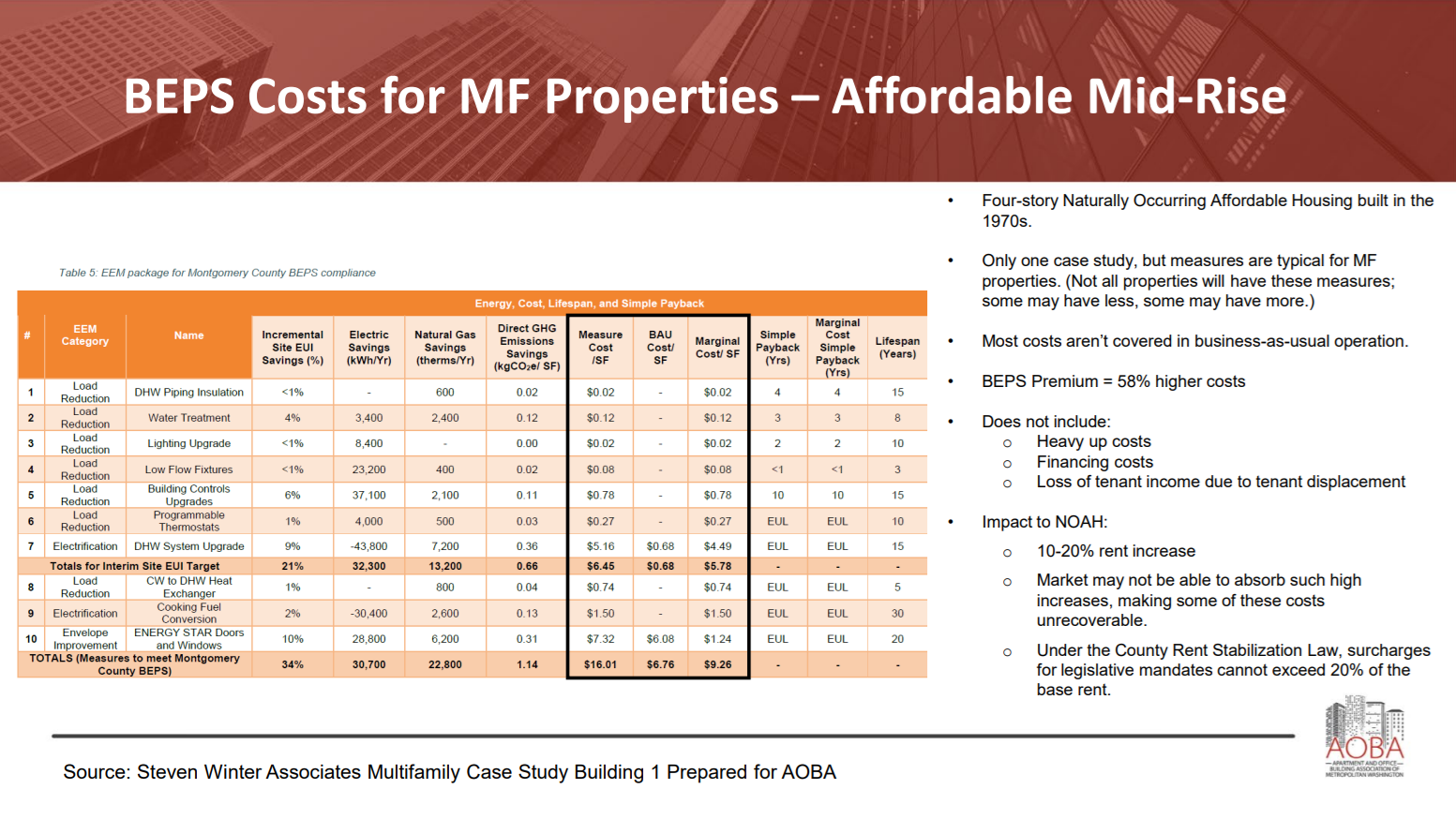

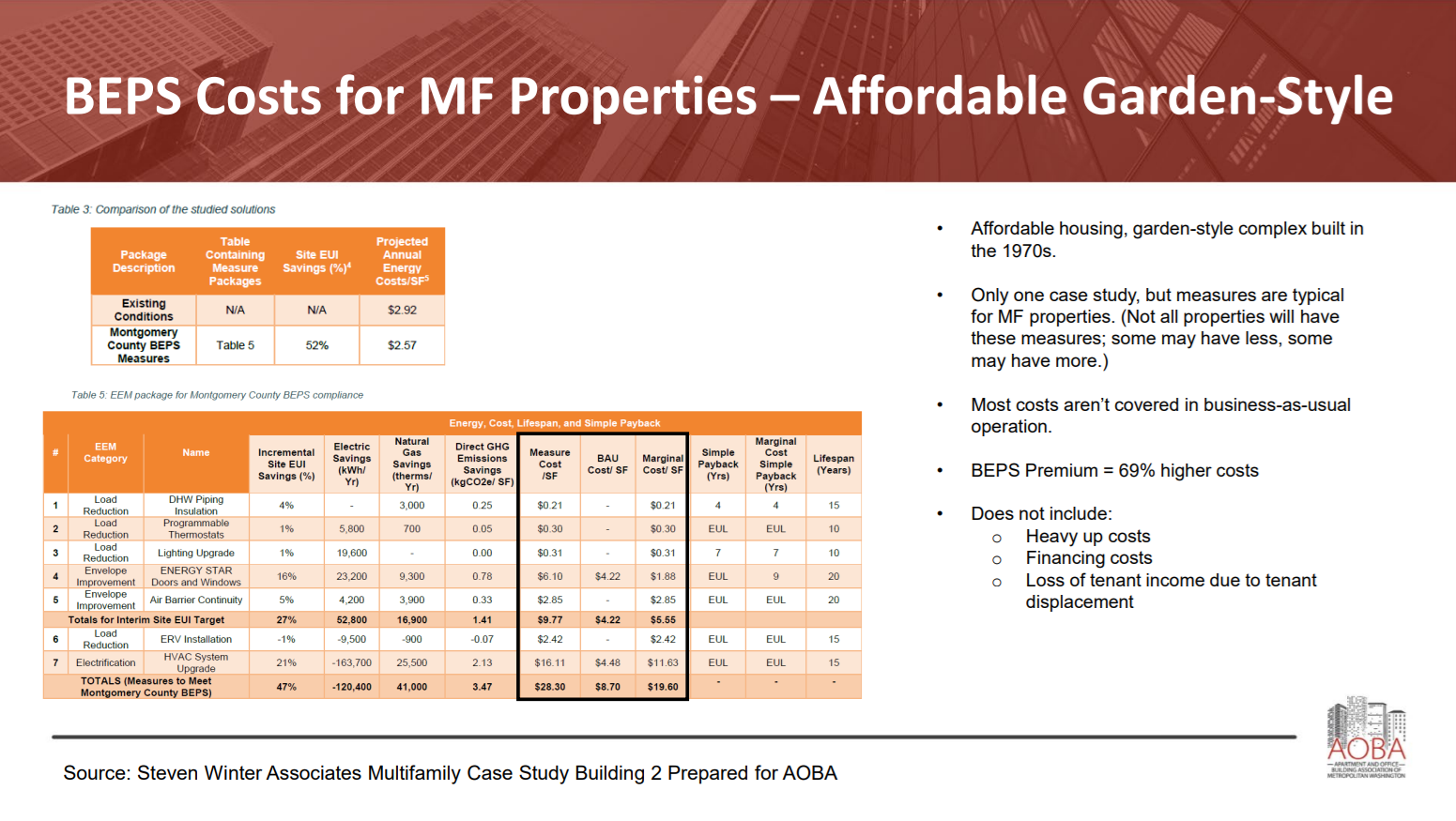

Those regulations are now before the council. On July 15, the Apartment and Office Building Association of Metropolitan Washington (AOBA) submitted a study of compliance costs by energy efficiency consultant Steven Winter Associates to the council. And – surprise! – the requirements are expensive to implement. Here are a few highlights.

1. The total capital cost for all multifamily building owners from 2021 through 2039 of zero-net-carbon standards will be $3.22 billion. Note that this does not include commercial buildings, of which those having 25,000 or more square feet are also covered. Lower standards produce lower costs, but fewer environmental benefits.

2. Some efficiency measures have payback periods of 10 years or less, meaning that they will eventually pay for themselves through energy savings. But many others do not, imposing continuous added costs for the effective useful life (EUL) of the building.

3. The slide below is a case study of a four story multifamily building constructed in the 1970s, described as an affordable midrise and an example of naturally occurring affordable housing. County requirements will impose a cost increase of 58%, which does not include heavy up (increased amperage) costs, financing costs and tenant displacement. Those costs would result in rent increases of 10-20%.

4. The slide below is a case study of a garden style multifamily building constructed in the 1970s, also described as an example of naturally occurring affordable housing. County requirements will impose a cost increase of 69%, which does not include heavy up (increased amperage) costs, financing costs and tenant displacement. Rent increases are not estimated, but if the smaller cost increase of the above midrise building resulted in 10-20% rent increases, you can guess what will happen.

But wait – the county also passed a rent control law last year that limited rent increases to inflation plus 3% with a hard cap of 6%. So how could any owner levy a 20% rent increase? The answer lies in Sec. 29-58 (d) of the law, which gives landlords the right to petition the county for a “limited surcharge for capital improvements,” one of which would apply “if the capital improvements would result in energy cost savings.” There are several conditions on such a surcharge, but if the petition meets them, the county’s housing director “must” grant it and it may allow up to a 20% rent increase in some circumstances. Regulations implementing the surcharge, as well as the rest of the law, have now been passed by the council.

The rent control law can always be changed if 20% rent increases become common, but here’s the problem. What happens if the county forces landlords to absorb energy cost increases of 50-60% without fully recovering them from tenants? Few landlords of any kind could eat that level of cost. Condo conversions offer no escape from energy performance costs since condos are covered by the law. That fact has generated a deluge of protests from condo associations and unit owners. One way for older building owners to get out of this jam is to tear down their old buildings and replace them with new ones that will be exempt from rent control for 23 years under county law.

And that brings us to a potential consequence that no county leader wants: the elimination of older buildings which provide naturally occurring affordable housing. The combined impact of energy mandates without cost recovery from tenants could kill off affordable housing, the preservation of which was one of the primary goals of rent control. The alternative – allowing cost recovery from tenants – also undermines affordable housing and emasculates the rent control law.

This is not the best advertisement for the wisdom of policy making in Montgomery County government.

And so this demonstrates the limitations of progressive command economics. County leaders wanted building energy standards for the sake of climate change mitigation, so they mandated them. County leaders wanted caps on rent increases to protect tenants, so they mandated them. Now those two mandates are on a collision course.

The only decision left is whom to designate as the crash victims.