By Adam Pagnucco.

Last week, when Council Member Kristin Mink joined Council Member Will Jawando in opposing the Planning Board’s Attainable Housing Strategies initiative, she recommended several alternatives in justifying her position. Among them was “supporting older condo buildings and townhouses with HOAs. Many of these properties are at risk of failing due to huge maintenance costs, often resulting in very high association fees.”

She’s right. They do face huge costs. Many of them are due to be imposed by the county government.

In a previous post, I outlined the collision course between two county laws awaiting implementation: the 2022 building energy performance standards (BEPS) law, which requires many commercial and multifamily buildings to meet county-mandated energy efficiency targets; and the 2023 rent control law, which caps rent increases. Compliance with one law threatens to undermine the other, thus pitting two progressive priorities against each other.

Perhaps the most intense heat directed against the building energy standards law has nothing to do with rent control, but instead with the fact that it applies to condo buildings. Individual condo owners and their associations are starting to discover that they will bear responsibility for expensive retrofits that will not be required of single family homeowners. In older condo buildings, the costs could be immense.

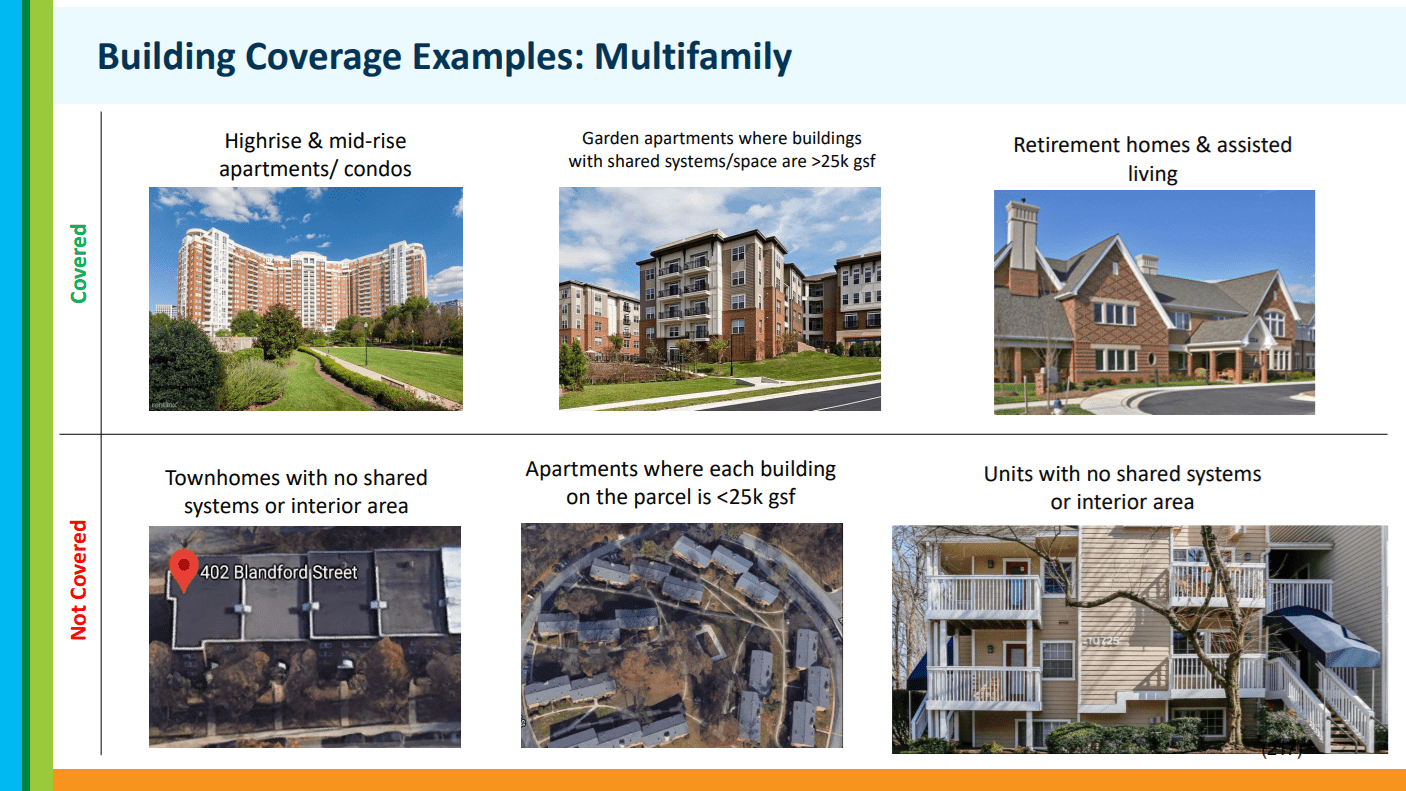

This slide from the county’s Department of Environmental Protection illustrates which multi-family residential buildings are covered and exempted by the BEPS law.

In reading through the comments made on the building energy standard regulations sent to the county council last year, one stood out to me for its extraordinarily detailed illustration of what could happen to condo owners under the BEPS law. (Note: those regulations were not approved, but as long as the law is on the books, some version of regulations must eventually be approved.) The writer is a senior citizen living in Friendship Heights, a transit-accessible community on the D.C. border. I am withholding the writer’s name as it’s not relevant to the content of the comments. Nevertheless, I suspect that this person’s views are far from unique.

The individual’s remarks are printed below.

*****

I am the owner (along with my wife) of a condominium apartment in the Willoughby, an 800+ unit apartment building in Friendship Heights, Maryland. I am submitting these comments in response to the proposed Building Performance Standards regulations recently published by the Department of Environmental Protection. [Number 17-23.]

Let me say at the outset that I recognize the seriousness of the world’s climate crisis and commend Montgomery County for its leadership in addressing this important issue. However, as the owner of an apartment in an older high-rise condominium building, I am concerned that the proposed regulations will have an unfair and potentially crippling financial impact on condo owners like us. The challenges presented by climate change are global in nature and cause. While it’s true that, in addressing environmental problems, we should “think globally and act locally,” the proposed regulations threaten to impose a potentially crushing financial burden on County apartment owners, while contributing relatively little to solving this globally-generated problem.

The Willoughby is one of the largest apartment buildings in Montgomery County. It was constructed in the late 1960s, long before the dangers of climate change were broadly understood. The 800+ units in the Willoughby are owned by a combination of resident-owners (approximately 60%) who live in their units and investor-owners (approximately 40%) who lease their units to others. A significant proportion of the Willoughby’s owners and residents are elderly, retired, and live on fixed incomes. The expense of complying with the proposed regulations, e.g., retrofitting our building with state-of-the-art energy saving features like new boilers and double-paned windows (assuming it’s even feasible), is likely to cost tens of millions of dollars. Because each of us owns our own apartments, and the apartment owners collectively own the building infrastructure, the proverbial “buck” stops with us—the individual owners. There is no “deep pocket” corporation who will pick up the tab for expensive energy efficiency improvements to our building. Instead, ALL THE COSTS—and they will be substantial—must be borne by individual apartment owners, likely from a combination of significantly increased monthly HOA fees and special assessments.

I am concerned that the high cost of meeting the proposed building performance standards may force Willoughby owners to sell their units at lower than market prices and move out, depressing property values in our building. In addition to disrupting owners’ lives and undermining their financial security, these proposed regulations are in tension with the County’s laudable policy goal of encouraging AFFORDABLE multi-family housing near Metro and other transit hubs, especially for its elderly residents.

At the most basic level, the proposed regulation is fundamentally unfair because it would impose significant energy reduction requirements and costs on owners of condominium apartments while exempting owners of single-family houses. This discriminatory focus on apartment owners ignores the fact that apartment owners are already doing their part to combat climate change by choosing to live in relatively smaller homes that leave a smaller environmental footprint.

The average size of a single family house in the United States is approximately 2,500 square feet. I would hazard a guess that in relatively affluent Montgomery County the average size of a single family house is larger than that, and maybe significantly so. On the other hand, the average apartment in the United States is only 887 square feet. Asking the owners of modestly-sized apartment homes to dig deep into their retirement and other savings to meet the proposed building performance standards while asking NOTHING of owners of much larger single-family houses in Montgomery County is not right. Perhaps if single-family home owners were asked to do more, the burden on apartment owners could be reduced.

In addition, it is not fair to set the proposed building performance standard for “multifamily housing” like the Willoughby at 37 kBtu/sq. ft., while proposing a much more relaxed standard for most other property uses, e.g., bars/nightclubs (220); fast food restaurants (220); restaurant/bar (219); retail/mall (81). Apartment buildings would also have to meet a performance standard significantly higher than financial offices (58); colleges/universities (57); hotels (60); and offices (55). [Oddly, the building category with a performance standard closest to residential apartment buildings is “prisons.” (38).] Like the exemption for single-family houses, these proposed standards ask owners of condominium apartments to do far more than their fair share. And unlike the other mostly commercial property uses that benefit from far more relaxed kBtu standards, there is no “deep pocket” corporate owner able to absorb the cost of the energy efficiency improvements that will likely be necessary for condo owners to meet its standard.

The proposed rules do acknowledge the potential for financial hardship and would allow building owners to submit a “building performance improvement plan” (BPIP) in lieu of meeting the performance standards if the building demonstrates it “cannot reasonably meet” those standards. To get their plan approved, the owners must demonstrate that they cannot meet the standards because of “economic infeasibility or other circumstances beyond the owner’s control.”

However, it is not at all clear what “cannot reasonably meet” or “economic infeasibility” means, or what kind of showing individual owners of the 800+ units in the Willoughby would have to make to meet this test. Would each condominium owner have to file individual income and asset data with the County? Would the building, instead, file a single document that incorporates both the owners’ individual and the condominium’s collective financial data? How would the condominium force individual owners to reveal and share WITH EACH OTHER AND THE COUNTY their personal financial information? Such forced disclosure would seem a massive invasion of privacy. And what is the hardship cut-off for triggering relief? How many tens of millions of dollars would the County expect individual owners to spend on improvements before the County would say they have paid enough? Would owners (or the building collectively) have to demonstrate that meeting the standards would lead to individual or collective bankruptcy? As you can imagine, these are questions that might keep a unit owner like me awake at night!

Moreover, the cost to condo owners of preparing a BPIP is not inconsequential. It will take an enormous amount of time, effort and money for the owners of a condominium association to demonstrate “economic infeasibility” or “circumstances outside the owner’s control.” The cost to the condominium association to hire the economic, engineering, legal and tax professionals and consultants necessary to consider, among other things, “all possible incentives, financing, and cash flow resources available,” do a “cost-benefit analysis of each potential energy improvement,” and develop a “retrofit plan” will be significant. Assuming the County approves such a plan, the condominium will be saddled for years with the costs of monitoring and reporting compliance.

In short, these proposed regulations, although perhaps well-intentioned, are neither fair nor reasonable. They exempt an entire class of homeowners (single family) while imposing potentially crushing financial burdens on owners of apartments in multi-family buildings. They set a far more stringent performance standard (37 kBtu/sq. ft.) for residential buildings than for many, if not most, other covered property uses even though residents of apartments are already doing their part to address climate and other environmental issues by living in modestly-sized homes in multi-family buildings. Lastly, the proposed financial “safety valve” (the BPIP) has far too many unknowns and uncertainties—what do basic terms like “cannot reasonably meet;” “economic infeasibility;” and “other circumstances beyond the owners control” mean—to provide condominium owners with reassurance that we won’t be subject to crushing financial compliance burdens.

I urge the County to withdraw and reconsider these proposed regulations.

Thank you.