By Adam Pagnucco.

Part One told a brief history of the Viva White Oak project. Today, let’s examine a crucial supportive element requested by County Executive Marc Elrich: a Tax Increment Financing (TIF) mechanism. No such thing has ever been used in Montgomery County before. What is it?

The proposed Viva White Oak project is massive, containing thousands of housing units and millions of square feet of retail and commercial space. That much development requires infrastructure. The 2014 White Oak Science Gateway Master Plan proposed that an elementary school and “ample parks and open space amenities, including civic greens, a local park, and an integrated trail and bikeway system” be constructed to support it. But that will cost many millions of dollars. Where will that come from? According to Elrich and project developer MCB Real Estate, a TIF is the answer.

TIFs have been used in the U.S. since the 1950s. Here is how the City of Baltimore, which has used TIFs many times, describes them.

*****

Tax Increment Financing (TIF) is a financing tool that capture and uses increased property tax revenues from new development within a defined geographic area to fund public infrastructure.

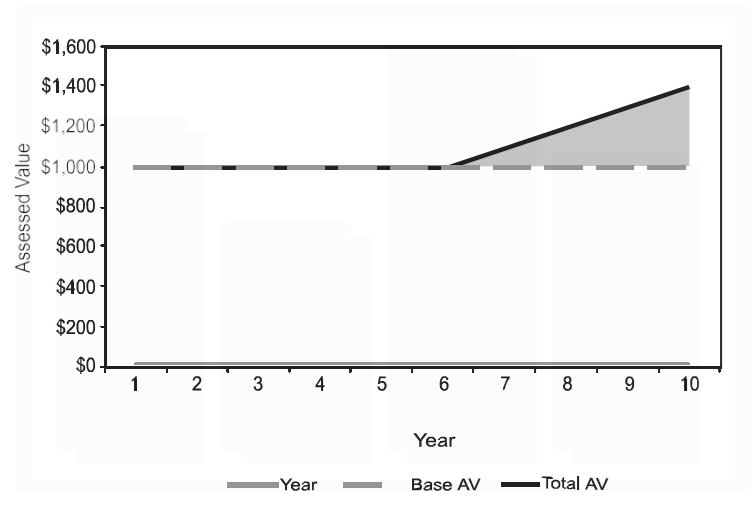

Tax Increment represent the taxes collected on the new assessed value within the development district. Revenues generated from properties within the TIF districts are split into two components:

Base Revenues:

This is the amount available before the TIF district is established.

They are shared amongst a mix of local government jurisdictions that have the power to assess property taxes: schools, cities, counties, and special districts.

Incremental Revenues:

These are new revenues in excess of the base revenue that are generated by development projects.

These monies are allocated to the TIF project.

Tax rate remains the same inside the development area as other City property, unless there is a revenue shortfall for debt service.

Incremental Revenues represented by the triangular area are the dollars allocated to the TIF Project.

Typically TIF bond proceeds are pledged to fund public City-owned improvements.

Bonds are not backed by the City’s full faith and credit.

TIF revenues not needed for debt service on the bonds go to the general fund.

When the bonds are repaid, all TIF revenues revert to the general fund as part of normal tax collections.

*****

So as a development proceeds, additional property tax revenues are used to back infrastructure bonds, which are used to build schools, transportation projects, parks and anything else needed to support the development. Once the bonds are paid off, all taxes are used normally.

Is a TIF corporate welfare? I don’t see it that way (and I generally oppose corporate welfare). TIFs charge property taxes like any other collection mechanism, but additional taxes created by new development are used to build infrastructure rather than to finance general spending. The arrangement is temporary and ends when the infrastructure bonds are paid off. TIFs do not inherently necessitate tax abatements. In fact, in the context of a tax abatement, the TIF would struggle to pay off its bonds.

Are TIFs good ideas? That depends on who you ask. Infrastructure to support development is a necessity. So are general funds used to support schools, public safety and other operating spending incurred by local governments in servicing new residents in TIF areas. TIFs temporarily sacrifice additional general operating spending in order to build infrastructure, a tradeoff that will appeal to some and arouse displeasure in others.

Back in 2010, the council discussed using a TIF to finance infrastructure associated with new development in White Flint. At that time, the administration of Ike Leggett opposed a TIF and proposed a tax district instead. Here is what Leggett wrote about TIFs.

*****

This was an approach that had been initially suggested by some in the development community and was discussed by Planning Board staff. This mechanism has been rejected for a number of reasons. As a funding source it has issues of reliability, constraints on fiscal management and equity concerns. Tax increment financing pledges increases in tax revenues to pay for infrastructure. As evidenced by recent history, the development cycle and reliability of projections can be difficult to predict and sometimes wrong. TIFs are dependent upon development moving forward on a predictable schedule. If redevelopment does not occur, the remainder of the County – and in this case the general fund – would have to pick up the fiscal obligations of the debt. This particular funding approach is more typically used in blighted areas and is better suited to large tracts of land that will be redeveloped rather than piecemeal property ownerships reflected in the White Flint Sector Plan area. The lack of assurance of a critical mass of redevelopment occurring is challenging for the issuance of debt, particularly in the context of the sector plan where improvements and capacity are critical to the implementation and staging of the plan.

It is also worth pointing out that a TIF would use tax revenues that are subject to Charter Section 305 limits and would therefore force the funding for these roads to compete with schools, libraries, fire stations, community centers, etc. throughout the County. A TIF also raises fundamental equity issues. Developers would be paying increased taxes based on increases in assessments if they redevelop. They would not be paying for infrastructure as has been historically and is currently required throughout the County. This would be a departure from the general and longstanding policy that development must pay for itself. While the rest of the county would bear the overall total expenses from redevelopment and the risk of carrying up to the full load of that funding if development did not take place as represented, there would be little risk to the development community and their revenues would be pledged to bettering White Flint only, rather than other areas of the County. Further, the County would lose significant flexibility as it manages through difficult fiscal years. Pledging revenues right off the top, while retaining the burden of providing the infrastructure is ill-advised, particularly given recent experiences with our economy.

*****

Leggett won this battle and a tax district was used in White Flint instead. Given the fact that White Flint has not fully developed (with the exception of Pike and Rose), there is little doubt that a TIF located there would not have raised anywhere near the money that would have been projected at full buildout.

Will a TIF work for Viva White Oak? That’s what the council and analysts on both its staff and in the Planning Department will be trying to answer over the next several weeks. In the meantime, the project has several other hurdles, such as the county’s development-killing rent control law and the massive cuts the Trump administration wants to implement to Viva White Oak’s neighbor, the FDA headquarters.

To address those questions, I went to the project’s developer, MCB Real Estate, to gather its opinions on those and other issues. My questions and their answers will begin next!