By Adam Pagnucco.

Word of Discovery Communications’ exit from Silver Spring has exploded like a bomb in local politics, prompting attacks by the state Democrats on Governor Larry Hogan and two outsider County Executive candidates on the county government. But the answer to the real question is not to be found in political soundbites: where does MoCo go from here?

Let’s start by acknowledging the unusual nature of Discovery. The only reason the company was in MoCo to begin with is that its founder, John Hendricks, moved here in his 20s and started it at age 30. If Hendricks had instead lived in, say, Philadelphia, the company would have been started there. Discovery was largely a stand-alone organization that was not surrounded by peers. When Hendricks retired as Chairman three years ago, it was probably inevitable that the company was going to move with media-packed New York City as a prime option. Accordingly, no one your author knows who has been associated with Discovery is surprised at its exit. While the company was important to Silver Spring, the departure of a firm like United Therapeutics, a key player in the local bio-tech industry, would have been more troublesome because of the county’s long-time efforts to build up that sector.

That said, Discovery will leave a big hole in Downtown Silver Spring. Its 1,300 employees are hugely important to Silver Spring’s lunch scene and happy hour crowds. (Anyone who sees the sheer number of people walking through the Georgia Avenue crosswalk near the building to access Ellsworth Place can appreciate this.) The building itself was constructed to house one tenant. Subdividing it for multiple tenants could be costly and challenging, thereby complicating its reuse. Discovery is looking to sell it but it may not be occupied for a while. Finally, the viability of Silver Spring as an employment center may be questioned by developers and tenants alike. Will the central business district continue to be a jobs base or will new development be overwhelmingly residential, thereby cementing Silver Spring as a bedroom community for D.C.? And could that worry be applied to most of the rest of the county? It’s telling that the two most prominent new office buildings in the pipeline, the Park and Planning headquarters in Wheaton and the new Marriott headquarters in Downtown Bethesda, are supported by public money.

Aside from the usual political elbow-throwing, the reaction of the county has focused on the financial incentive it offered to Discovery to stay. County Executive Ike Leggett said in a statement, “The County and State made a substantial proposal designed to accommodate Discovery’s challenges. Together, we were ready to provide considerable incentives to retain their presence in the County.” Bethesda Magazine quoted Leggett as saying, “The incentive package was one of the largest offered to a company during his time in office, although he did not reveal specific details about the package Tuesday.” We hear it was in the same ballpark as the $22 million offered by the county to retain Marriott with more money coming from the state. Notably, New York State offered no incentives to attract Discovery.

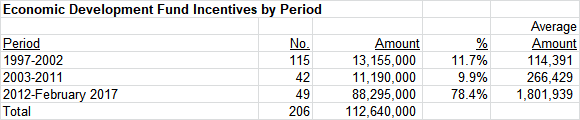

The county’s reliance on corporate welfare for economic development is one of the great untold local stories of the last few years. Business incentives, usually contained in grants convertible to loans when job targets go unmet, are disbursed through the county’s Economic Development Fund (EDF). They are approved in secret under an exemption from the state’s Open Meetings Act. Residents do not learn of the amounts spent or the recipients’ identities until after the agreements are signed. Summary details are available only in annual EDF reports released during the County Council’s budget process. Aggregations of those reports show that the county has approved 49 incentives totaling $88.3 million between 2012 and February 2017, of which 35 incentives worth $79.7 million were used for retention. That’s right, folks – over the last five years, the county agreed to pay almost $80 million to existing employers to stay. Six of those incentives consist of annual disbursements payable over periods ranging from six to fifteen years, thereby continually weighing on the tax base. For the sake of comparison, the county is spending $80 million for libraries and recreation combined this fiscal year. Just this month, the County Executive has proposed a mid-year savings plan of $60 million, including a $25 million cut for MCPS, while corporate welfare remains untouched.

Since 2012, MoCo’s corporate welfare has skyrocketed.

Is this really working?

MoCo should be an economic development leader. We have tremendous advantages, including a large federal presence, a highly educated workforce, good schools, lots of investment in transportation projects (including the Purple Line), substantial wealth in some of our neighborhoods, low crime and virtually no public corruption. Few localities in the nation can say they have all of these things. But instead of being a growth leader in the Washington area, the county’s total employment growth of 3% between 2001 and 2016 ranked 20th of 24 Washington-area jurisdictions measured by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. MoCo’s jobs base and its real per capita personal income have not recovered from the Great Recession. And now our economic problems have contributed to a $120 million budget shortfall. We’re not leaders, we’re laggards. We must do better.

Discovery is headed out the door, but if we want to create the next generation of Discoveries, we are going to need a more creative and disciplined economic development strategy than relying on bribes to retain big employers. We are going to have to save tax hikes for desperate times and not pass them simply because we’d like to spend money. We are going to have to invest more in transportation and education and pay for it by restraining growth in the rest of the budget. We are going to have to do things like ending the liquor monopoly, directing more of our county reserves into community banks where they can finance local job creation, cutting impact taxes near Metro stations to encourage transit-oriented development and raising them elsewhere to pay for it, and getting rid of redundant bureaucracy. (Fun fact: we are the only local jurisdiction that requires two different independent agencies to sign off on every record plat, which drives developers banana-cakes.) And after passing numerous employment laws, we should give employers time to adapt to them rather than immediately introduce more mandates. If we implement this kind of agenda, maybe we could attract and retain businesses without handing out tens of millions of dollars in corporate welfare.

Economic development is tough. It’s about more than one big employer. It takes time. It takes multiple components. Most of all, it takes discipline. If our next generation of elected leaders learns these lessons from Discovery’s departure, we will come back stronger than ever. If not, Discovery won’t be the last high-profile employer to say adiós.