By Adam Pagnucco.

In Part Two, we detailed how MoCo has experienced an exodus of taxpayer income since 1993. But MoCo is not alone: many large jurisdictions in the Washington region have suffered from taxpayer flight over the last decade.

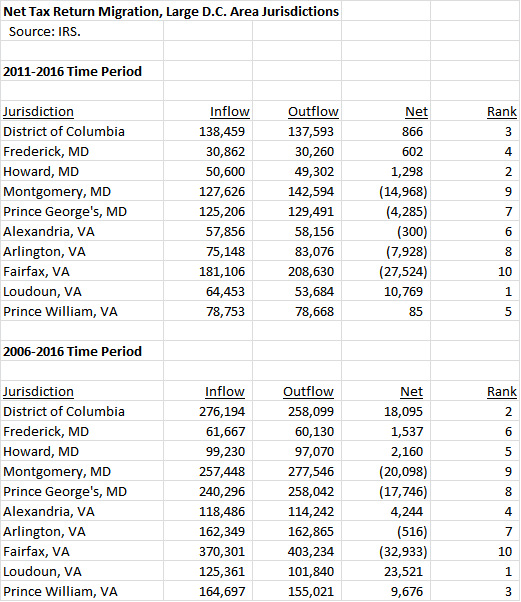

Below is a chart showing the net change in tax returns for the ten largest jurisdictions in the region. We show net change for two time periods: the last five years (2011-2016), which include the recovery from the Great Recession, and the last ten years (2006-2016), which include the pre-recession peak, the recession itself and the recovery afterwards. MoCo ranks nine out of ten in both periods with only Fairfax faring worse. Loudoun is the only jurisdiction showing significant in-migration in the last five years while D.C. was comparable to Loudoun over the last ten years.

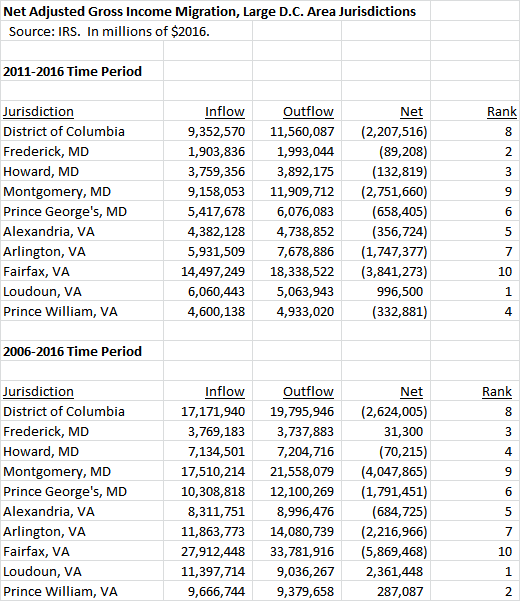

Next, we show the net change in adjusted gross income (AGI), measured in 2016 dollars, over the two periods. Once again, MoCo is the second-worst jurisdiction in the region with only Fairfax trailing. Notably, only Loudoun had a net inflow in the last five years and Loudoun, Prince William and Frederick had net inflows in the last ten years.

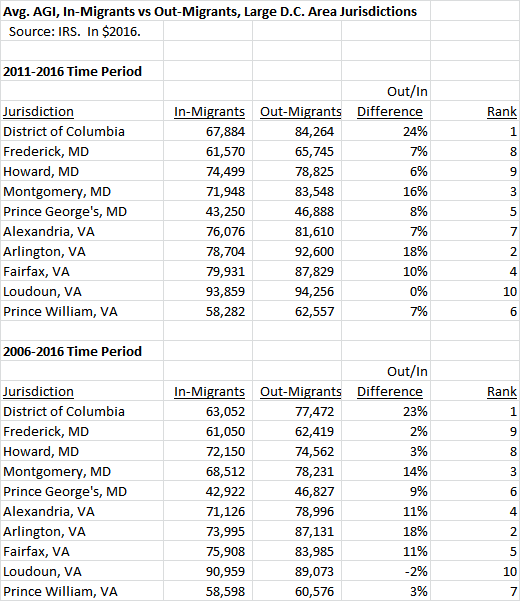

Finally, we show the average AGI of in-migrants vs the average AGI of out-migrants over the two periods. In every jurisdiction except Loudoun (during the 2006-2016 period), in-migrant AGI was lower than out-migrant AGI. MoCo’s gap was the third largest.

This is a bad picture for MoCo and not a very good one for the region as a whole. What is going on here?

First, as has been previously noted by George Mason Professor Stephen Fuller, the entire Washington region’s economy has slowed down since the Great Recession. That is reflected in the deterioration of the numbers above between the last five years and the last ten years. The “new normal” has not been kind to anyone in this area and that includes MoCo.

Second, Fairfax has been affected by taxpayer income losses even more than MoCo. Like MoCo, Fairfax is a huge county with huge bills to pay and nightmarish traffic congestion. But Fairfax also shares a long land border with Loudoun, which has grown dramatically in past decades and is currently the nation’s wealthiest county. Of the $5.9 billion that Fairfax lost to taxpayer flight in the last decade, $2.5 billion went to Loudoun.

Third, in addition to the number of taxpayers leaving on net, MoCo’s problem is the big gap in income between those coming in and those leaving. One would expect to see such a gap in places like D.C. and Arlington, the two jurisdictions with the biggest income gaps shown above. That’s because both places attract lots of young people who work in and near downtown D.C. and then move out when they earn more and have kids. That explanation does not work well for MoCo, which has a much lower percentage of young people in its population than D.C. or Arlington. And yet MoCo’s gap, which is third in the region, has been significantly bigger than the gaps in Fairfax and Howard, two jurisdictions of similar wealth, in the last five years.

We have seen how MoCo compares to its large neighbors in tax migration overall. But what about direct inflow and outflow relationships? To whom does MoCo lose income? And from whom does MoCo gain income? We will begin examining that in Part Four.