By Adam Pagnucco.

Compared to traditional elections, ranked choice voting (RCV) produces different outcomes only two percent of the time. That’s because most elections in which RCV is an option don’t actually use ranked choice because they have an unopposed candidate, an insufficient number of candidates to trigger ranked choice or a candidate who crossed the winning threshold (like an absolute majority) in the first round.

Here are a few other things to consider about RCV.

Details Matter

Different jurisdictions using RCV have wildly different rules for how they use it. What are the thresholds for eliminating candidates? In which elections – generals, primaries, specials – are they used? How is RCV applied to races with multiple seats? St. Paul, Minnesota claims to have saved money by using ranked choice because it eliminated primaries. With RCV, are primaries needed?

Transparency is Important

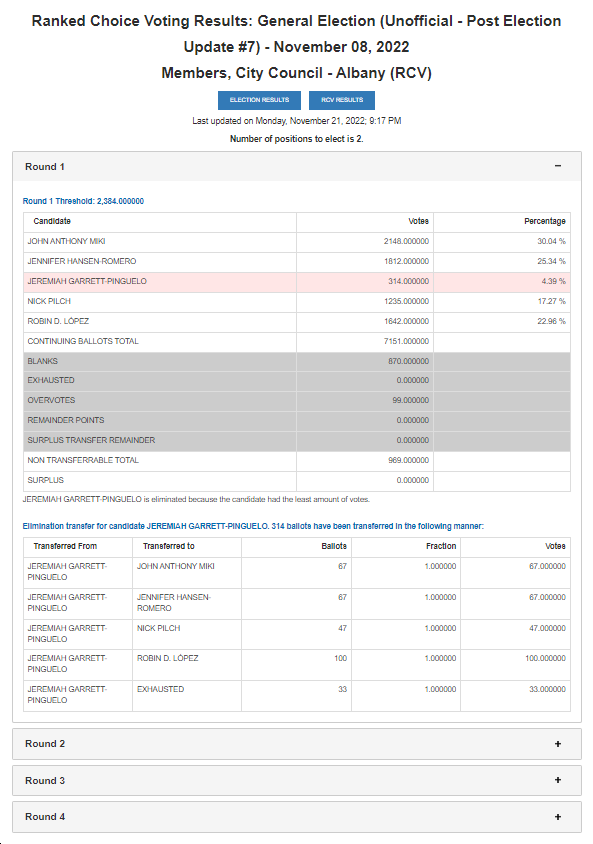

If they are to have confidence in RCV, voters have to understand what happens to the votes for losing candidates in successive rounds. Alaska’s example from Part One is a straightforward example, but elections with lots of rounds are challenging to present. Consider the following result from the 2022 municipal election in Albany, California. This is just one round of four. How can the important criteria of transparency and understandability best be balanced?

Ballot Counting in RCV Can Take Awhile

22 elections in my dataset, or 13% of the elections in which ranked choice was triggered, went for 10 rounds of counting or more. The leader was the 2013 Mayor’s race in Minneapolis, which had 35 filed candidates and went for 34 rounds. Despite all of the counting, the first round leader (Betsy Hodges) never relinquished her lead and was elected. The second-place candidate (Mark Andrew) also never relinquished his position throughout the entire count.

It’s worth noting that the 2018 Montgomery County Council At-Large Democratic primary had 33 candidates. If RCV was in effect back then, how long would it have taken to tabulate those ballots and declare winners?

What About Recounts?

I know of one RCV race that went to a recount: the 2021 Minneapolis Ward 2 City Council election. That race had five filed candidates and went for three rounds, producing a 19-vote margin for the first round winner. (The candidates who finished first and second in the first round retained their positions in the last round.) After a recount, the winner did not change but the margin was cut to 14 votes. 9,777 votes were counted in the final round and the recount took four days. Now imagine how long a recount might take with more than a hundred thousand votes (typical of MoCo executive and council at-large races) and a long list of candidates.

RCV Needs Guard Rails

Few elections using RCV or not can match the insane 2009 contest for Minneapolis Board of Estimate and Taxation. Among the 261 candidates, these “individuals” each received at least one vote: Abolish This Board, Barack Obama, Batman, Bernie Madoff, Brett Favre, Bugs Bunny, Darth Vader, Donald Duck, If Any, John Q Public, Lady Ga Ga, Lizard People, Mickey Mouse, Mr. M. Mouse, Nay, No Preference, None of Them, Pop-Eye, Spaghetti Monster, Why and “Sorry, I Know None Of These Well Enough To Select Any.” The result of the election, which went through five rounds of counting, confirmed the same two candidates who finished atop the first round of voting. Was it really necessary to check if the voter who selected “Lizard People” had a second choice?

The Final Verdict

Here is the bottom line: because RCV produces the same outcome as traditional elections 98% of the time, there is little reason to support it or oppose it. It is unlikely to produce the glowing change predicted by its advocates. It is equally unlikely to produce the doomsday scenarios predicted by its opponents.

However, because of its complexity, there is reason to question whether RCV increases the cost of elections and/or the time required to count ballots. A fiscal note on a 2021 state bill calling for RCV in Montgomery County estimated that ranked choice would cost the county $2 million to set up in the first year with hundreds of thousands of dollars annually in future years. If county elections resemble Takoma Park RCV elections held since the city adopted the system in 2007 – elections which so far have not produced any different outcomes than traditional voting – it’s reasonable to wonder whether spending this money makes sense. This would be particularly true if the system prolongs vote counting, which already takes way too long in Montgomery County.