By Adam Pagnucco.

Montgomery County voters don’t like property tax hikes. In 1990, 2008 and 2020, county voters approved different versions of a charter amendment limiting increases in property taxes. The current charter limit, approved in November 2020, requires a unanimous vote of the county council to raise the real property tax rate. And yet, County Executive Marc Elrich’s new proposal for a 10 percent property tax hike is not subject to the charter limit, thereby evading the wishes of voters. How is he able to do that?

This column tells the story of how the state effectively nullified county charter limits on property taxes, as well as the role of the man now known as the Hand of the King.

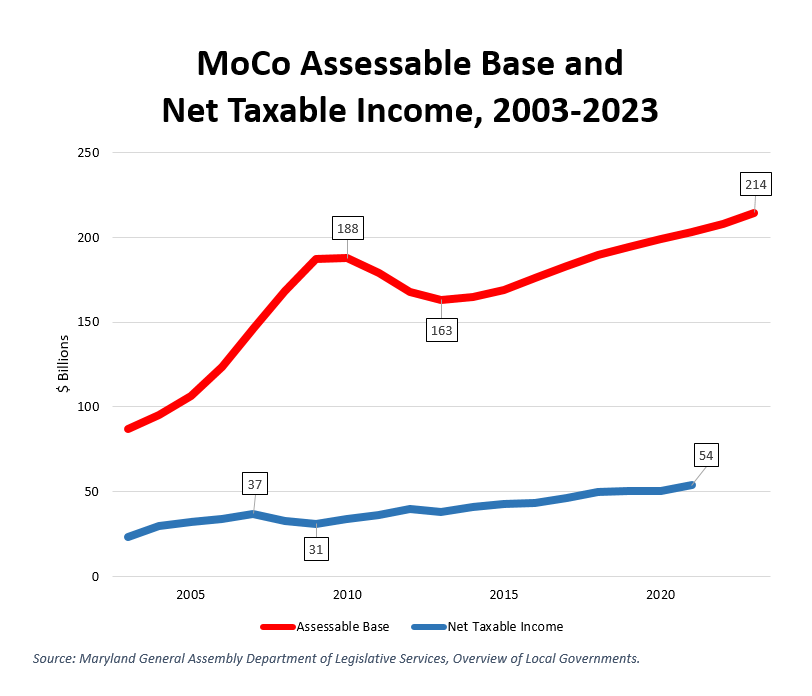

This tale begins, as so many things relevant to the present time do, with the Great Recession. All localities have occasional economic downturns, but what made the Great Recession stand out was its brutal impact on the two main sources of county revenue: the assessable base and net taxable income. The chart below shows these two measures in Montgomery County over the last twenty years.

The Great Recession reversed years of growth in the two pillars of the county’s budget. The assessable base supports property taxes, the county’s top revenue source, and it fell from $188 billion in 2010 to $163 billion in 2013. Net taxable income supports income taxes, the county’s second largest revenue source, and it fell from $37 billion in 2007 to $31 billion in 2009. The disintegration of the county’s economy set off a desperate scramble to protect the county’s bond rating and reserves. County Executive Ike Leggett and the county council of that time implemented a number of emergency measures to save the county, including a doubling of the energy tax, abrogation of collective bargaining agreements, substantial spending cuts and attrition of roughly a thousand positions in county government.

One of the areas the county cut was school funding. The county slashed its local per pupil contribution to MCPS three years in a row, an unprecedented event bitterly resisted by Superintendent Jerry Weast and the MCPS unions. This caught the attention of the General Assembly, which presided over a school funding law known as “maintenance of effort” that withheld increases in state school aid to jurisdictions cutting per pupil contributions without state permission. That did not stop Montgomery County from cutting MCPS funding, and it did not stop other counties facing similar financial difficulties from doing the same. By 2012, the General Assembly had seen enough.

The school funding issue converged with another thorny matter pitting the counties against the state: teacher pensions. For decades, the state had covered the cost of teacher pensions as a way to support public schools. But Senate President Mike Miller argued that since local school boards set pay packages that were used to calculate pensions, local boards and the county governments who funded them should be responsible for paying those pensions. After many years of pushing, Miller finally recruited Governor Martin O’Malley and Speaker Mike Busch to his cause and the three worked to shift teacher pensions to the counties. This also occurred in 2012.

I was working in county government at the time and I helped assemble a statewide effort to stop the shift. We had an unwieldy coalition of county governments, school boards, Republicans and unions – especially MCGEO. It was a surreal experience to attend meetings at the Maryland Association of Counties building with tea party county commissioners on one side of the table and MCGEO President Gino Renne on the other side. Whatever our differences, we understood that a pension shift would cost the counties big time. And the county that had the most at stake was Montgomery County, which had more teachers than any other jurisdiction.

But we had a problem – our own county’s Democratic state legislators, who took orders from Miller, Busch and O’Malley. And of those, no one was more influential than State Senator Rich Madaleno. Rich has many appealing traits – he is brainy, funny, charming, self-deprecating and cultivates everyone around him. His two favorite subjects are his kids and the Caps. He is someone with whom you can disagree and still come away thinking, “What a nice guy!” But his greatest strength is that he understands budgets in ways that few other politicians do. During his time in Annapolis, there may have been two or three people in all of Maryland who knew the state’s budget as well as he did. Rich was so knowledgeable that his colleagues looked to him for guidance on budget matters large and small. And on the teacher pension issue, Rich had thrown in his lot with Mike Miller.

Rich was one of the architects of the 2012 budget deal that proved costly for MoCo. The deal had three components. First, the maintenance of effort law was revised to make it harder for counties to cut local per pupil contributions to schools. In fact, the new version of the law is so strong that if a county tries to cut local per pupil spending without state permission, the state can seize the equivalent amount from the county’s income tax distribution and send it directly to the school district. Second, the counties would now owe part of the cost of teacher pensions to the state. MoCo now pays over $60 million a year to the state for teacher pensions, more than any other county in Maryland. Third, to remedy its budget problems, the state levied an income tax increase that directly targeted MoCo. Montgomery County has one-sixth of the state’s population but it paid 41% of the 2012 income tax hike. A majority of the county’s state legislators supported all three elements of this deal.

As you might imagine, MoCo government leaders of that era were outraged. One argument they made was that the county’s charter limit on property taxes might make it financially impossible to obey the maintenance of effort law and pay for teacher pensions without gutting the rest of county government. So the General Assembly inserted language in the maintenance of effort law allowing counties to circumvent their charter limits to fund school budgets. The language, which is now contained in Md. Education Code Ann. § 5-104(d)(1), reads:

Notwithstanding any provision of a county charter that places a limit on that county’s property tax rate or revenues and subject to paragraph (2) of this subsection, a county governing body may set a property tax rate that is higher than the rate authorized under the county’s charter or collect more property tax revenues than the revenues authorized under the county’s charter for the sole purpose of funding the approved budget of the county [school] board.

Since that time, at least three counties with charter limits on taxes – Anne Arundel, Prince George’s and Talbot – have used this provision to evade their charter limits and pass property tax hikes. Elrich tried to join them in 2020 but the council shot down the idea. Now he is trying again, backed up by one of the architects of the charter limit loophole – former State Senator and current Chief Administrative Officer Rich Madaleno.

Rich has paid no price for the events of 2012. In fact, as the top manager in county government, he is more powerful than ever. There are times when I see certain actions by the executive branch – these tax proposals, the attempted delay of the Capital Crescent Trail and the attempt to single-track the Purple Line – and I wonder if Rich is, at least on some issues, the actual leader of the Elrich administration. (Rich is a long-time Purple Line opponent.) Regardless, his influence is beyond question, and if Elrich does not run for another term, Rich may be the favorite to succeed him.

But that’s a question for the future. Today, the Hand of the King reigns. We shall see if anyone can stop him.