By Adam Pagnucco.

New statistics assembled by county council staff show slight recent drops in violent crime and property crime and a much larger drop in crimes against society. However, both violent and property crime rates remain much higher than before the COVID pandemic.

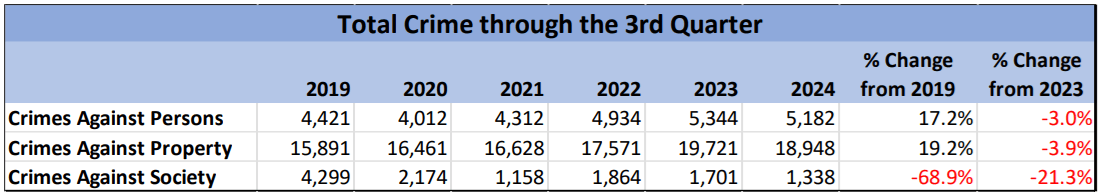

First, let’s look at the overall crime stats from the county council Public Safety Committee packet by public safety analyst Susan Farag. The table below shows crimes by major category – violent, property and society – since 2019 through the third quarter.

Through the third quarter, violent crime has dropped by 3% and property crime has dropped by 4% compared to last year. However, violent crime is up by 17% and property crime is up by 19% compared to 2019, the year before the COVID pandemic. Crimes against society are down substantially over the period.

Why have crimes against society declined so much? Most crimes in that category relate to drugs – distribute/manufacture, possession or other. In 2019 through the third quarter, there were 3,955 crimes in those categories. In the same period in 2024, there were 925 such crimes – a drop of 77%. Since it’s unlikely that drugs are disappearing from the streets, I have previously asked whether police are adequately enforcing laws against drug crimes.

Besides the overall drop in crime, here are a few other stats that struck me.

Firearms related crimes are increasing.

Most of these crimes are either aggravated assaults or robberies. In the first three quarters, they totaled 357 in 2022, 374 in 2023 and 394 in 2024.

Let’s remember that police seize firearms from vehicles and some local politicians (like Council Members Will Jawando and Kristin Mink) want to make vehicle searches more difficult.

Carjackings are way down.

These are the numbers of carjackings through the third quarter.

2019: 15

2020: 19

2021: 43

2022: 55

2023: 73

2024: 41

Yes, carjackings are still much more frequent than during the pandemic, but at least the county is making progress here.

Almost a third of people arrested for crimes live outside the county.

69% of people arrested for crimes in the county live in the county. The next most common locations are Prince George’s County (9%) and the District of Columbia (7%).

This reinforces a point I have heard State’s Attorney John McCarthy make in public: comparing demographics of arrestees and people subject to traffic stops to MoCo’s population demographics is misleading. Substantial numbers of these folks don’t live in the county, and when a sixth (or more) of them come from jurisdictions like Prince George’s and D.C., that will cause a demographic skew in the data. Politicians and advocates should take this into account when using such data.

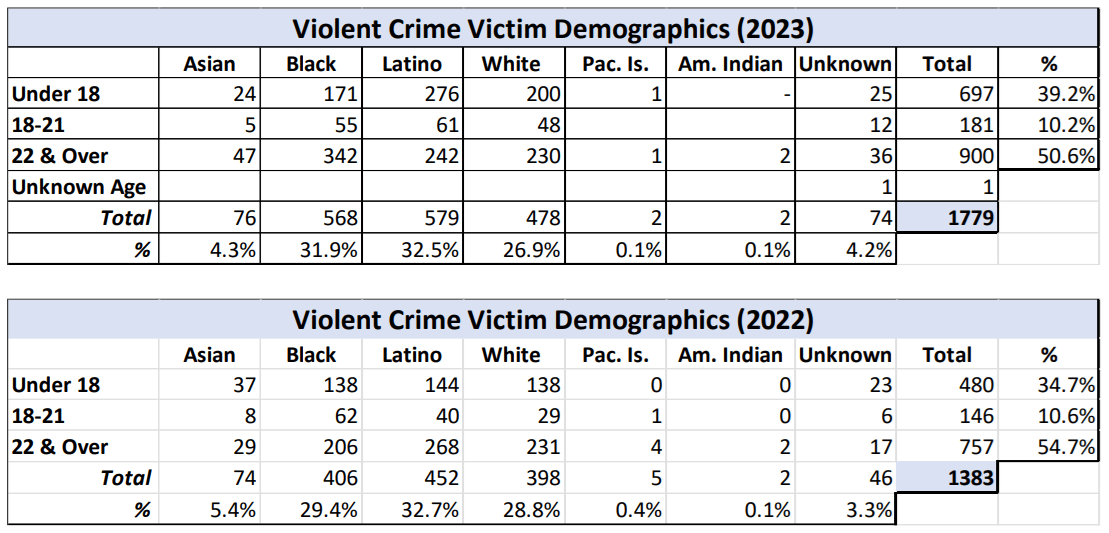

Most violent crime victims are people of color.

More than 60% of violent crime victims in 2022 and 2023 were either Black or Latino. The table below shows the demographic distribution of crime victims.

I have a post in the works that includes much additional data on this issue but let’s state this for now: advocates for defunding police (like Council Member Mink) are not doing Black and Latino residents any favors.

Police staffing shortages are a problem.

I have reported on police staffing shortages before. In March, I described a police staffing bomb in which a change to the county’s pension program could facilitate an exodus of up to a third of the county’s officers. According to the findings below by Susan Farag, the council’s public safety analyst, shortages are already causing problems.

*****

Staffing Shortages impact the ability to prevent and suppress crime. Police cannot control call volume or the severity of those calls. When the Committee was last briefed on Police staffing, there was a 14% sworn vacancy rate and an 18% professional staff vacancy rate. The Department advises that shortfalls have had a cascading effect on its ability to suppress crime. The Department’s primary obligation is to respond to calls for service. When officers have free time, they can proactively engage in crime suppression efforts. Since there are fewer officers available, there is less time for proactive crime suppression and community engagement. To combat this, the Department has used overtime to fill vacant patrol shifts. The Department has also worked with its labor partners to allow non-patrol officers to work overtime on patrol. These stopgap measures have helped staff vacant patrol shifts, but the Department advises this is not a long-term sustainable strategy. MCPD indicates that sustained overtime can lead to officer fatigue, which can then lead to health issues. And over the long term, forced overtime can reduce officer job satisfaction and effectiveness, which can lead to both departure from the workforce and unsatisfactory performance.

Short staffing also reduces the Department’s ability to temporarily assign officers to various initiatives and projects that improve community safety. It also hampers the Department’s ability to send officers to additional training.

*****

If this is occurring now, what happens after the staffing bomb explodes?

It’s welcome news that crime is down over last year, even if it’s just a little bit. But the county has more work to do to deal with its police staffing problems and get crime back down to pre-pandemic levels. This issue is sure to be on the minds of voters in the next round of county elections.