By Adam Pagnucco.

It’s one of the oldest stories in government. Suppose a government gets into financial trouble and can no longer pay its bills. What’s it going to do? It could raise taxes. It could cut spending. It could make some other government pay the bills, assuming it has the power to do so. That last tactic is especially attractive because then someone else would have to raise taxes and/or cut spending and, of course, take the heat for doing so.

It’s called shift and shaft. I witnessed a master class in this when I worked at the Montgomery County Council.

Back then, the Great Recession devastated state and county budgets all over the nation. Maryland Governor Martin O’Malley did everything he could to protect the state’s AAA bond rating through an all-of-the-above strategy – tax hikes, cuts and cost shifts to the counties and municipalities. First came cuts to highway user revenues, which is state transportation money shared with local governments to pay for transportation expenses, along with community college and police funding. Then came proposals to cut K-12, program open space money and library aid. That was followed by a partial shift of teacher pension payments, which had once been fully borne by the state, onto the counties. (That shift now costs Montgomery County government more than $77 million a year.) MoCo was definitely victimized by these shifts, but it was hardly an innocent victim because it cut tax duplication payments to its municipalities. That set off years of arguments between county leaders and the many mayors and town councils in the county. Shift and shaft on down the line indeed.

Now it’s happening again. Governor Wes Moore is confronting a hulking structural deficit and – just like O’Malley – he is responding with cuts and tax hikes. (Meanwhile, Virginia has a $3.2 billion surplus and Governor Glenn Youngkin is proposing tax cuts.) And just like O’Malley, Moore is proposing cost shifts onto the counties.

A fiscal briefing by the state’s Department of Legislative Services outlines the shifts. It comments:

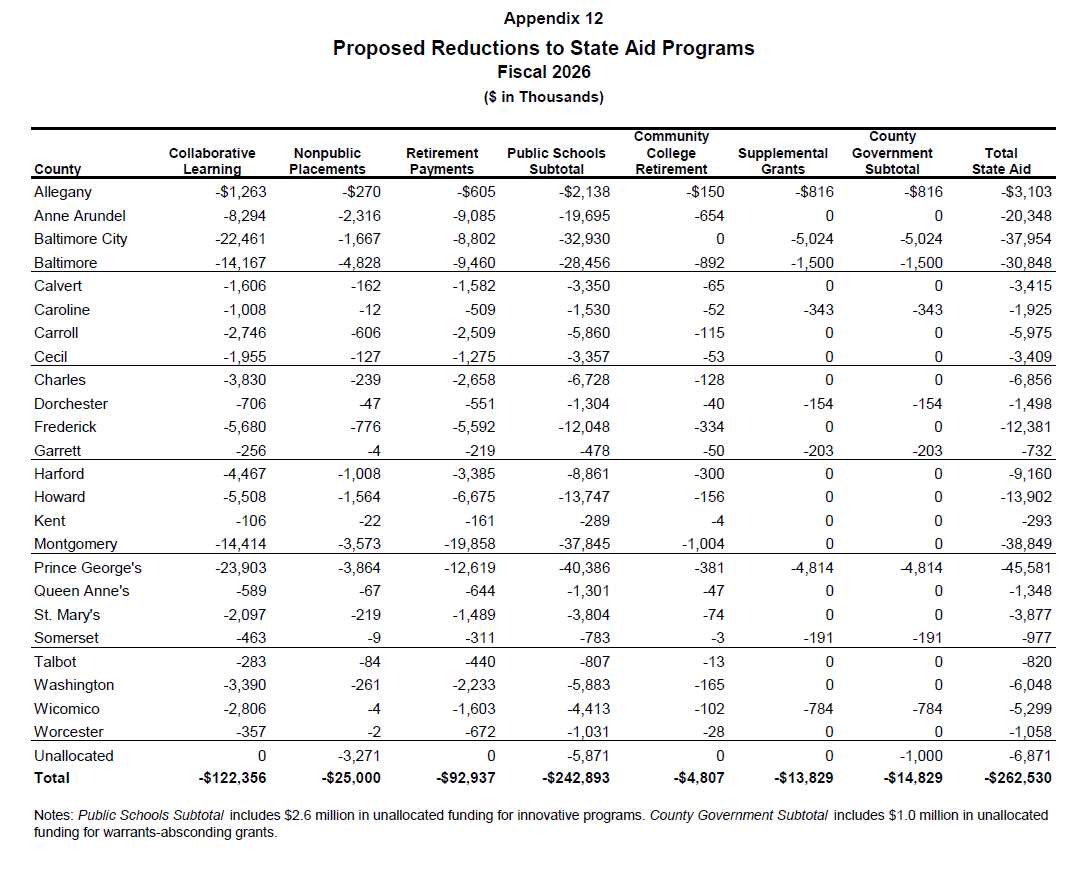

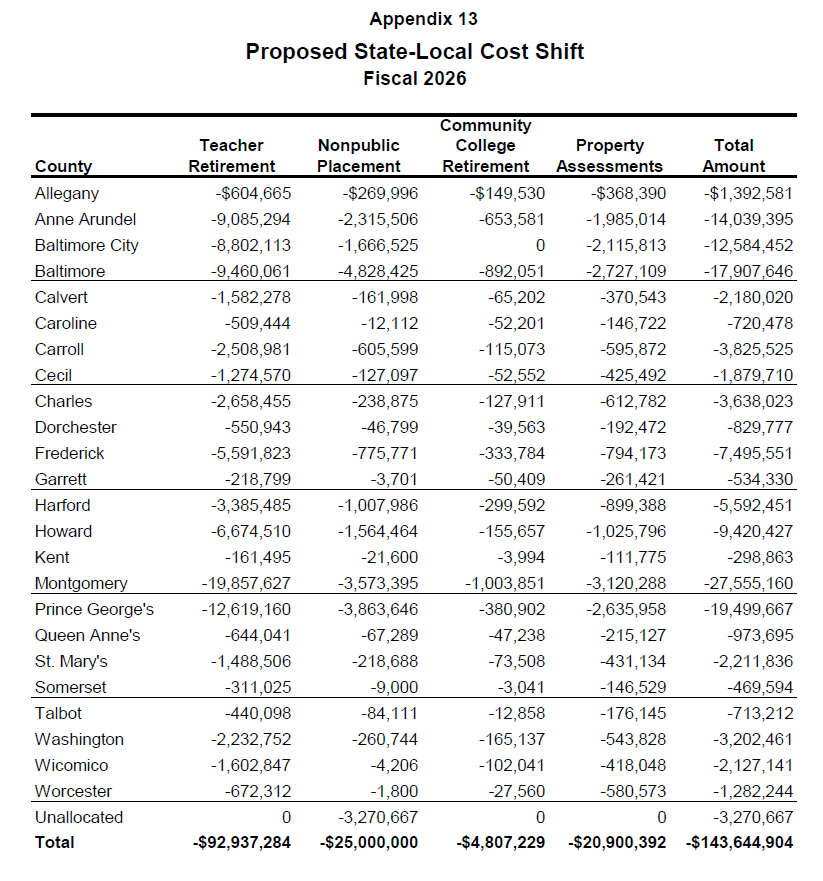

The budget plan shifts $144 million of costs to local governments by increasing the local share of the cost of property valuations ($20.9 million), requiring locals to pay a larger share of teachers’ retirement costs ($97.7 million), and increasing the local contribution for nonpublic placements ($25.0 million). Local governments will also receive $124 million less aid than expected to fund teacher collaboration time (but the mandate is also relieved) and $15 million less than fiscal 2025 for other mandates.

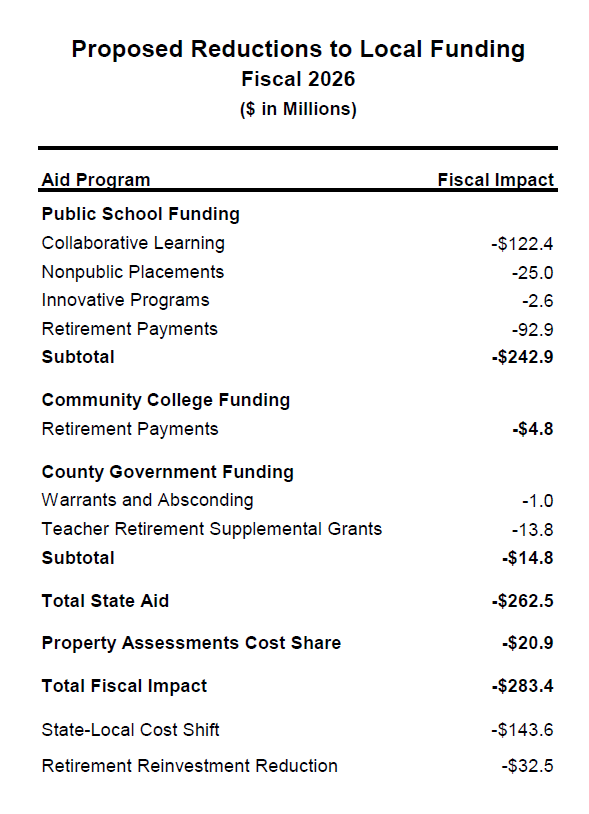

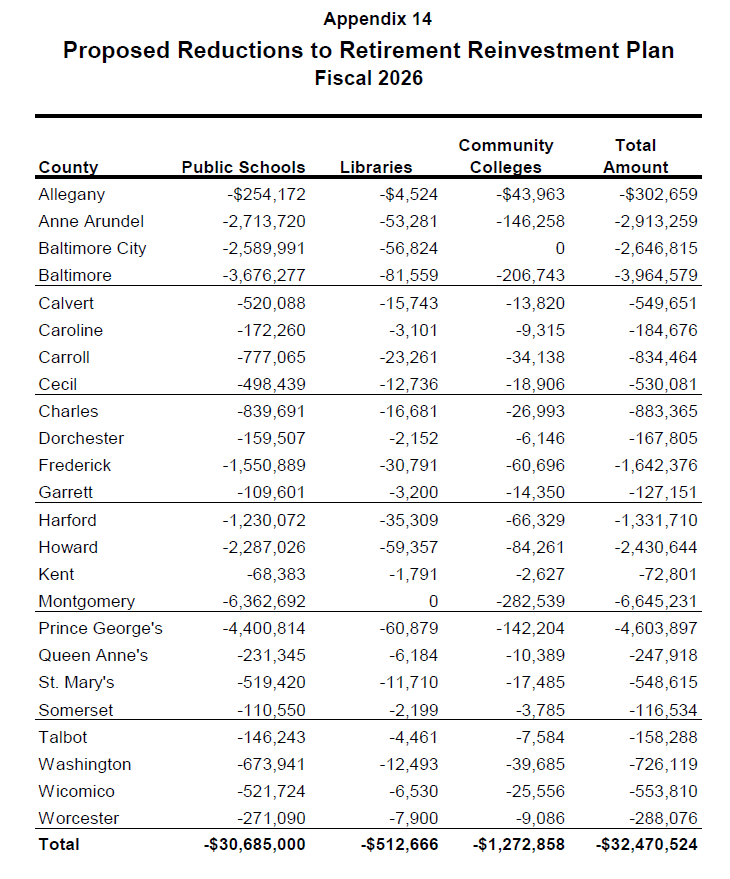

There is more than that. The page below summarizes the full scope of cost shifts and local funding reductions.

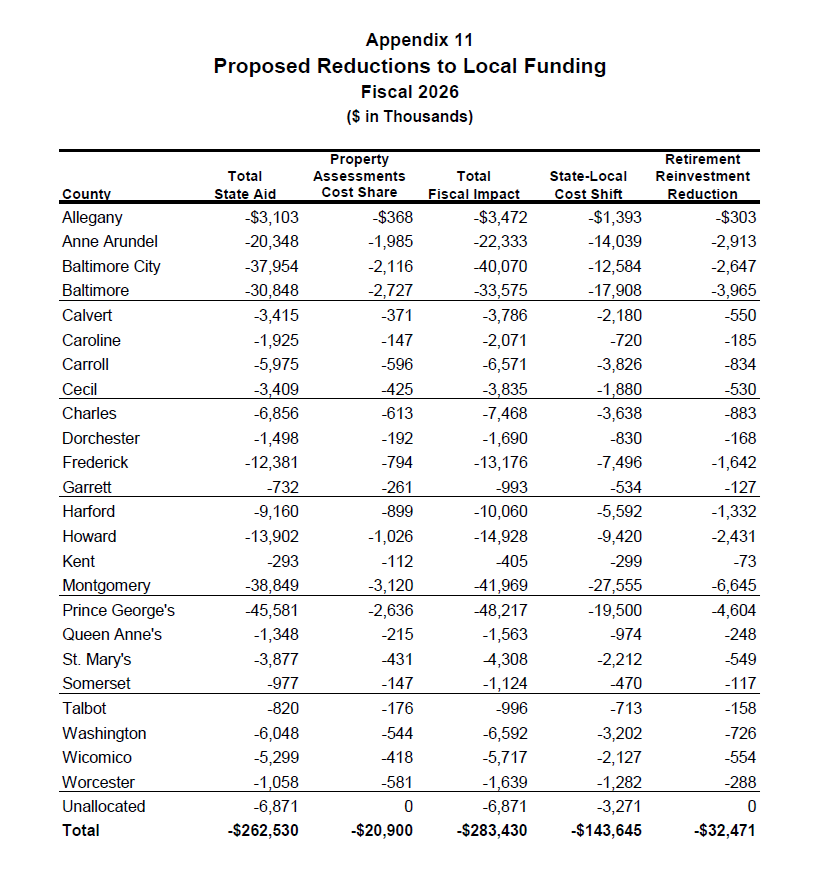

What’s it mean for you? The next four pages outline the shifts (and state aid reductions) by county. MoCo bears one of the biggest liabilities with $39 million in state aid reductions, $3 million due for increased property assessment costs, $28 million in cost shifting and nearly $7 million for retirement costs. Note how most of this money applies to public schools, which is by far the single largest category of state aid to local governments.

The governor’s fiscal plan has been widely portrayed in the press as progressive since it establishes higher rate income tax brackets for high income people and includes a four-year 1% surcharge on capital gains in excess of $350,000. But the total picture is more complicated. For example, his proposal to eliminate itemized deductions will clobber middle-class people with large home mortgage deductions. And if the counties react to the above cost shifts with property tax hikes – the most potent revenue raising tool they have – those increases will affect everyone, including renters.

But hey, the logic of shift and shaft is that it’s not the state’s problem. It’s the problem of county executives and county legislators, and possibly of municipal elected officials if the counties do their own cost shifts. And you know where the shaft is ultimately headed?

You guessed it. The taxpayers.