By Adam Pagnucco.

Montgomery County is the home of Maryland progressivism. It was the first county in the state to ban smoking in restaurants, enact a living wage law, pass a bag fee, ban private use of pesticides, create a local Earned Income Tax Credit and protect transgender residents from discrimination. It has the biggest county budget of any jurisdiction and has the largest Health and Human Services budget BY FAR. Every single state and county-level elected official is a Democrat and almost all of them are strong progressives. So this must all be supported by an overwhelmingly liberal voting base, right?

Not exactly.

MoCo’s political system is underwritten by three things. First, it has closed primaries that are limited to party members. Unaffiliated voters can only vote for non-partisan offices (like school board seats) in primaries. Second, because the county is so heavily tied to the federal government, the Republican Party is tainted by its association with the tea party, right-wing demagogues, government shutdowns, debt limit crises and the sequester. This is a huge burden on the county’s GOP. Third, turnout in the primaries is low and falling. A grand total of 42,692 Democrats voted in every one of the last three gubernatorial primaries (2006, 2010 and 2014), which determine the election of the County Executive, County Council, State Senators and Delegates. That’s just four percent of the population. These folks get swamped by election-time mail and email and the county leaders owe their election to them.

These three factors have together produced a closed political system that is accessible only to Democrats, and very liberal Democrats at that. But the general electorate is much more diverse. Over the last three gubernatorial cycles, non-Democrats accounted for roughly 40% of the county’s general election turnout. And the Democrats are not necessarily all liberals. Council Member Phil Andrews ran for County Executive last year on an unabashed anti-tax, anti-union platform. In the summer of 2013, he was polling in the mid-teens among Democrats. In the 2014 Democratic primary, he received 22% of the vote. The fact that more than a fifth of primary Democrats embraced an anti-tax, anti-union candidate should give progressives pause.

But the real evidence for the sentiments of the voters comes from how they vote on ballot questions and charter amendments. These questions are decided in the general elections, not the primaries, and voters outside the Democratic four percent get to play. Consider the last three important county-level questions.

The Ficker Amendment, 2008

Former basketball heckler and perennial right-wing candidate Robin Ficker placed a charter amendment on the ballot that required all nine County Council Members to approve any property tax increase that would exceed the rate of inflation. Similar amendments had failed in the past. The County Executive, the entire County Council and a large progressive coalition spearheaded by labor opposed it. But the same general electorate that gave 72% of its vote to Barack Obama for President also approved the Ficker Amendment by a 51-49 margin.

The Ambulance Fee, 2010

The ambulance fee, which was intended to be paid by insurance companies to supplement the county’s Fire and Rescue budget, was a top priority of the County Executive and the county employee unions and it was passed by the Democratic County Council. It was opposed by the Volunteer Fire Fighters, Council Member Phil Andrews and the Republican Party and was petitioned to the ballot. The reasons for opposition differed; the volunteers worried that the fee would deter people in need from calling ambulances, while others simply opposed a new government fee. The Executive and the unions campaigned hard to pass it. The general electorate rejected the fee by a 54-46 margin.

Police Effects Bargaining, 2012

The politics of this one were a bit murky. The Democratic County Council unanimously passed a bill repealing the right of the police union to bargain over the effects of management decisions and the Executive supported it. Both the Democratic and Republican parties also supported the legislation. But labor vehemently opposed it and responded by picketing county Democratic Party events and eventually taking over part of its Central Committee. This was a big test for labor’s power in the county and the police union and its allies went all out to defeat the legislation. The general electorate upheld it by a 58-42 margin.

In every case, when general election voters were asked to weigh in, they chose what was arguably the less progressive position. And in every case, they went against the position of the county government employee unions.

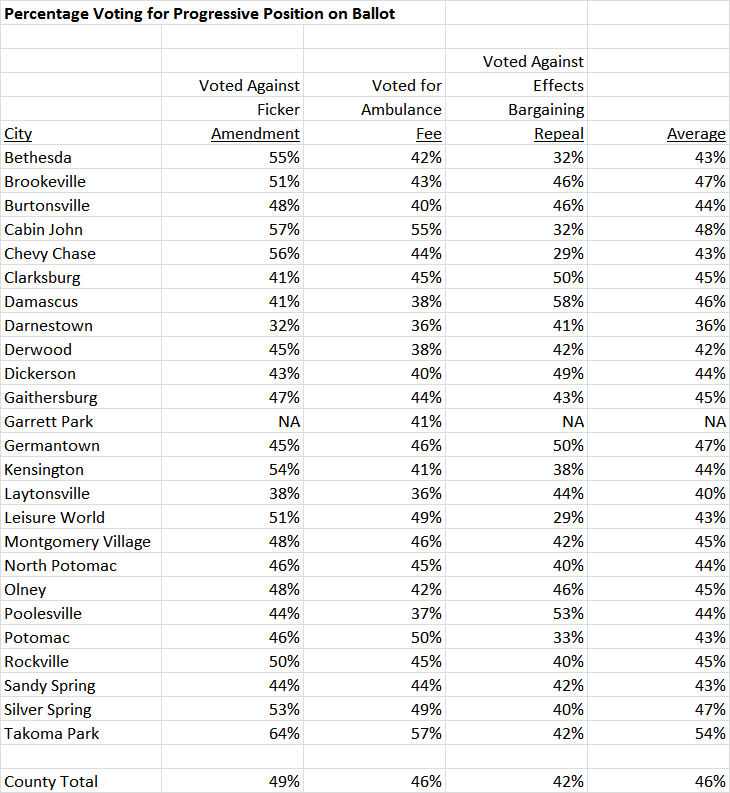

The county is not a monolith. It’s a big jurisdiction with more than a million people and its various sub-components have different political leanings. For example, Takoma Park is famous for its liberalism, but Damascus leans towards the GOP. I totaled up the precinct results of all three ballot questions for each city and town in the county to determine which ones went for the more progressive positions (no on the Ficker Amendment and the police legislation, yes on the ambulance fee) and which ones did not. Here are the results.

Not a single part of the county adopted the more progressive position all three times. Only two areas – Cabin John and Takoma Park – sided with the more progressive position twice (opposing the Ficker Amendment and supporting the ambulance fee). Ten areas – Burtonsville, Darnestown, Derwood, Dickerson, Gaithersburg, Laytonsville, Montgomery Village, North Potomac, Olney and Sandy Spring – voted against the progressive position all three times. The referendum on effects bargaining was influenced by the fact that many police officers live in Upcounty areas like Clarksburg, Damascus, Germantown and Poolesville. Many presumably liberal areas in Downcounty favored reducing the bargaining rights of the police union. Bethesda, Cabin John, Chevy Chase, Leisure World and Potomac went against labor by two-to-one or more. Even Takoma Park voted against labor by 58-42%. Here’s an interesting fact: in these three instances, the only time the general electorate agreed with the Democratic County Executive and a majority of the Democratic County Council was when they wanted to reduce public employee bargaining rights. Is that truly a liberal voter base?

So the politics of county voters are considerably more diverse than their progressive elected leaders. What does that mean? It’s highly unlikely that the Democrats will be removed from power. The county’s Republicans are too weak, too underfunded and in many instances too conservative to pick up more than a seat or two (if that). And there is no other organized political movement to take on the Democrats. The real danger is that the business community, conservatives and single-issue groups will seize the voter tools available to them – charter amendments and ballot questions – and begin overturning progressive legislation and limiting the authority of county government on a strategic basis. Given the past history of the general electorate and depending on the issue, they just might succeed.