By Adam Pagnucco.

This year marked the fifth cycle of county races I have studied and I have never seen anything like what happened with Brandy Brooks.

In 2018, Brooks ran for council at-large and was one of the breakout candidates of the cycle. Running from the left, she received endorsements from MCEA, MCGEO, Casa in Action, SEIU Local 32BJ, Progressive Maryland, the local AFL-CIO and others; qualified for matching funds in public financing; and ran informally with MCPS teacher Chris Wilhelm as “Team Progressive.” She wound up finishing seventh of 33 candidates and did particularly well in Montgomery Village, Silver Spring (both Downtown and East County), Wheaton, Takoma Park, Burtonsville and Glenmont/Norbeck, all areas with lots of Black, brown and/or progressive voters. After the race, she stayed involved and ran unsuccessfully for a planning board appointment.

When Brooks declared for a council at-large seat again, she raised money in public financing at a lightning pace. That was followed by a rush of progressive endorsements, after which she looked like the strongest council at-large candidate to join the three incumbents on the dais. Then she blew herself up in April in one of the strangest scandals in MoCo political history, which was later chronicled in excruciating detail in the Intercept. Several endorsers dropped her, including MCEA, Casa in Action, Jews United for Justice Campaign Fund and the Democratic Socialists, and both MCEA and Casa switched their endorsements to her opponents. Other groups who might have been expected to endorse her but instead avoided her included SEIU Local 500, SEIU Local 32BJ, the AFL-CIO, Progressive Maryland and MCGEO.

The result of all this was one of the biggest collapses in the history of MoCo politics. Brooks went from being one of the favorites to finishing seventh of eight candidates. She finished in the top four in only 8 of 256 voting precincts. The only local areas in which she did NOT finish next to last were Clarksburg, Dickerson and Germantown (where she finished fifth) and Burtonsville, Glenmont/Norbeck, Silver Spring East County and Takoma Park (where she finished sixth). (See my methodology post for definitions.)

Most observers blamed the scandal for the meltdown. It certainly caused her to lose important endorsements and probably deterred others. But there is another reason for the outcome, one that may have prevented her from winning even in the absence of the scandal: imprudent campaign financial management.

In graphic terms, a campaign financial plan looks like a long, grinding climb up a hill followed by jumping off a cliff. There are two reasons for this: fundraising takes a long time and the biggest expenses, especially mail, digital and TV (if applicable), occur near the end of the campaign. Therefore, campaigns must save money in the beginning so they can spend a lot at the end. This means controlling early expenses – especially staff costs.

A good example of this is Hans Riemer’s 2018 council at-large campaign, which finished first of 33 candidates in the primary. The chart below shows Riemer’s cumulative net receipts – money in minus money out – for 18 months in the cycle. From March 2017 through January 2018, Riemer was raising money and minimizing expenses. The spikes in his net receipts were due to distributions of county matching funds since he was in public financing. Riemer’s cash peaked in the late winter, and then – BANG! – his money was out the door after April to pay for mail and other expenses. After election day, he had less than $20,000 in his account, but he had won the primary so his mission was accomplished. This is textbook campaign finance management.

Now let’s go to this year’s cycle and compare Brandy Brooks to the top two finishers, Evan Glass and Will Jawando. Brooks raised $300,550 in total, good for fifth in the field. In the January 12, 2022 campaign finance reports, Brooks showed a gross raise of $230,132, which was then best in the field as Tom Hucker had not yet entered the race. All of this shows that Brooks was an able fundraiser. Glass had a total raise for the cycle of $373,154, second to Hucker, and Jawando was third with $343,297. In gross raise, Brooks was not that far off from Jawando.

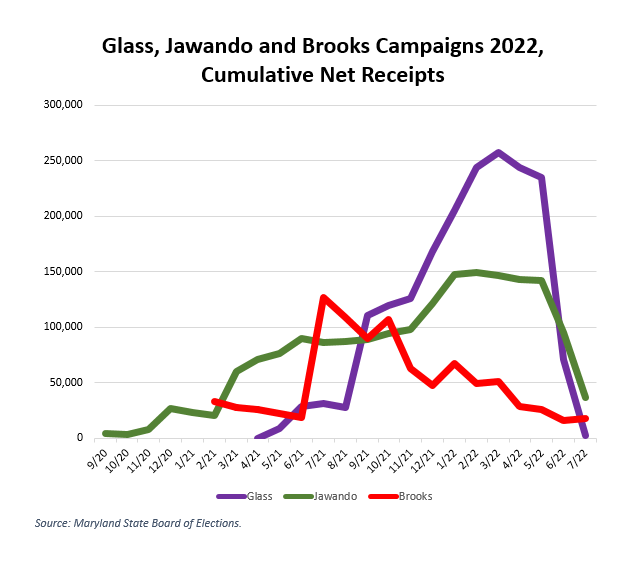

The chart below shows cumulative net receipts by month for Brooks, Glass and Jawando over the cycle. The curves for Glass and Jawando look like Riemer’s 2018 curve. Each of them saved money through the early spring and then spent large sums, principally on mail, in the last couple months. That is how campaigns are supposed to be run. Brooks peaked in July 2021 – a year before the election – and then often spent money faster than it came in. How could she be competitive at the end?

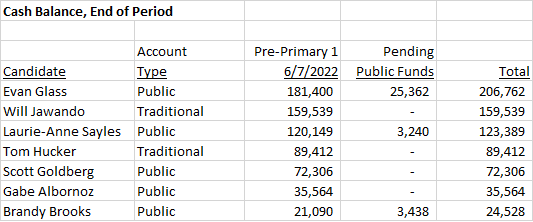

The table below shows cash on hand and pending public funds on June 7, 2022, right at crunch time for the election. Glass and Jawando were flush with cash, ready to rain money on the mail houses. Laurie-Anne Sayles also had six digits in the bank. Brooks had $25k, with more than 90% of her fundraising at that point already gone. Scandal or not, endorsements or not, she was done.

So what happened to the money? Political campaigns, at least those at the county council level, have three main categories of spending: mail (including postage), staff (including consulting fees), and digital (including phone, text and video).

Mail is invariably the largest category, usually accounting for between a third and half of council campaign expenditures. Brooks spent nothing on direct mail and just $7,289 on postage, which accounted for 2.4% of her expenditures.

Staff usually accounts for 20-40% of council campaign expenditures. Brooks spent $180,337 on wages, benefits, consultant fees and payroll management, or 60% of her expenditures. None of her opponents were in that range.

Brooks’s staff spending squeezed out her mail budget and may have cost her the race even without her scandal. This should be a cautionary tale for all future Montgomery County candidates.