By Adam Pagnucco.

Recently, former Council Member Hans Riemer published a guest column in Maryland Matters claiming that the county council had made “historic progress on housing.” There is no question that the past council passed some helpful measures. But data on housing construction shows no sign of actual progress – yet.

The list of legislative, planning and budgetary initiatives cited by Riemer are real. They include the passage of Thrive 2050 and many master plans, more public money for affordable housing, tax abatements for housing at Metro stations and the abolition of school-crowding moratoriums on housing construction. This agenda should result in more housing construction.

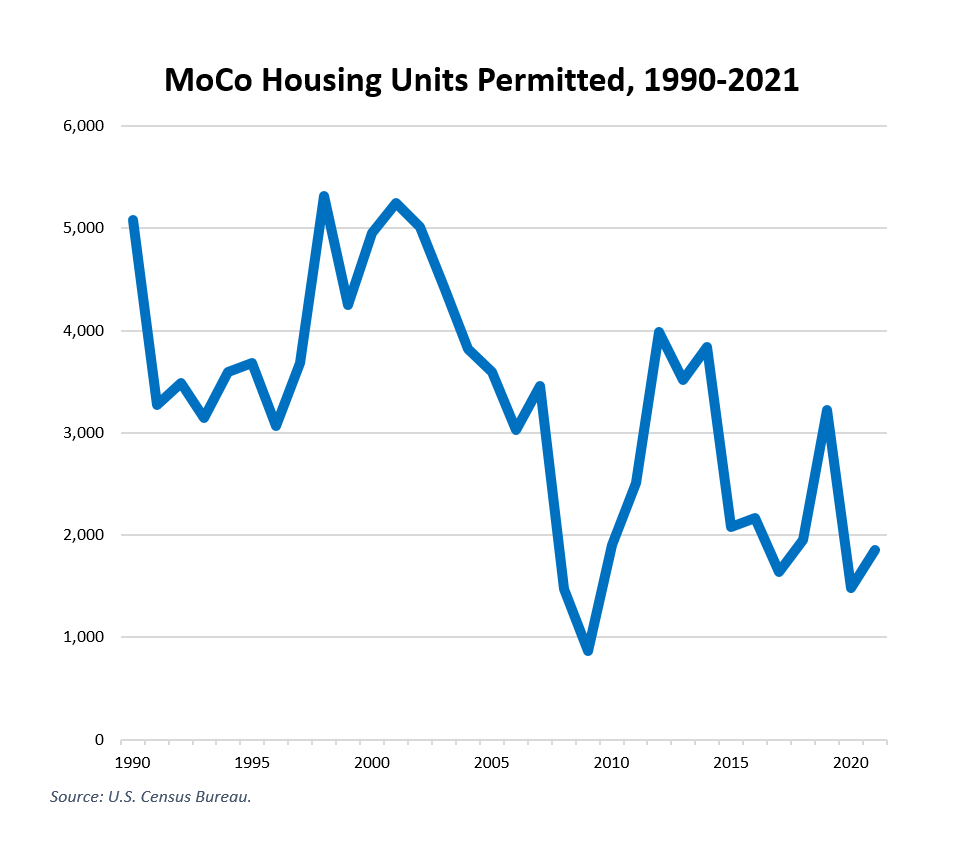

But so far it has not. The chart below shows housing units permitted in Montgomery County from 1990 through 2021. From 1990 through 2007, the county permitted an average of 4,006 units per year. Since then, it has permitted an average of 2,315 units per year. The two-year period of 2020 and 2021, in which 3,343 units were permitted, is the worst period in the series other than the Great Recession years of 2008-2010.

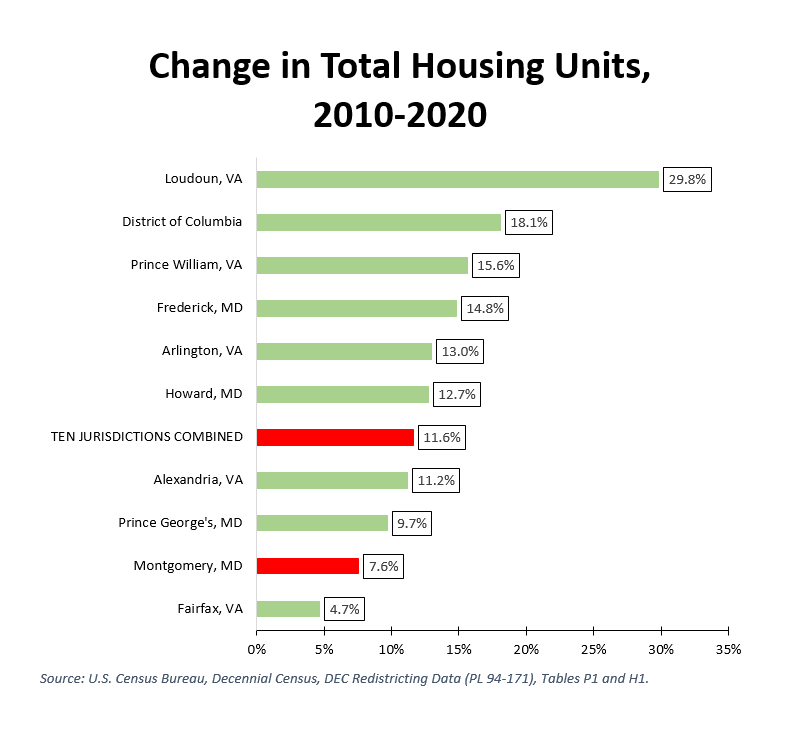

Housing construction is down across the region from the go-go years of the 1990s and the early 2000s. But even then, Montgomery County’s performance on housing supply is worse than most of its peers. The chart below uses decennial census data to show the increase in housing stock in the ten largest jurisdictions in the D.C. region between 2010 and 2020. Over that period, MoCo was the second-worst performer in the region, leading only Fairfax County.

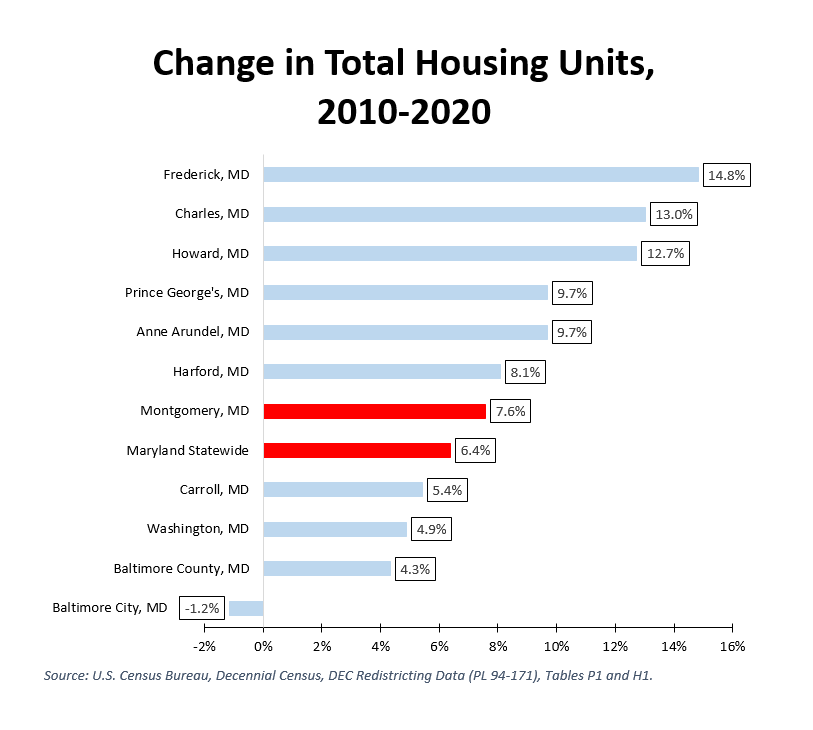

The chart below shows the same data in comparing Montgomery County to other large jurisdictions in Maryland. MoCo’s housing stock increased faster than the state average, which was pulled down by abysmal performance in Baltimore City. But we lagged most other large counties in the state, especially Frederick, Charles and Howard. We also lagged Prince George’s County.

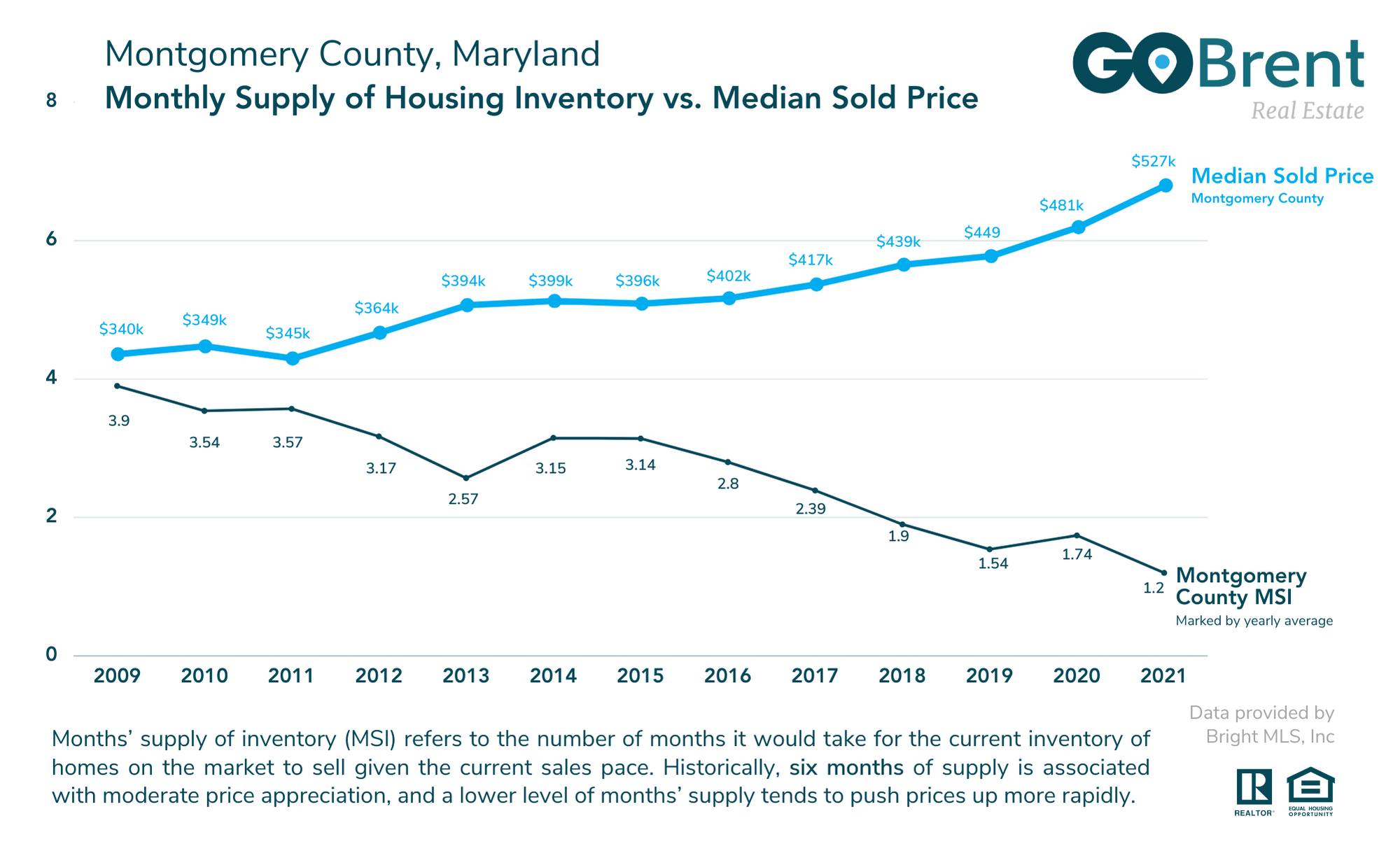

The result of this failure to build housing is real estate broker Liz Brent’s chart on housing for sale and median sale prices, which is reprinted below. Inventory of homes for sale has been declining over the last decade, contributing to rising median home prices. We are not the only jurisdiction to suffer from this phenomenon, but so far, our housing policies have not allowed us to break out of it.

Why are we not aggressively building housing? We should be building a lot more of it given the long list of master plans we have passed over the last decade allowing more density, not to mention the county’s zoning rewrite of 2014. My sources in the real estate industry point to a number of problems including the county’s failure to build infrastructure called for in its master plans; its failure to create jobs, which makes new housing less attractive for prospective owners, tenants and financiers; its occasionally lengthy development review procedures; its difficulty in attracting young people due to the presence of more amenities in D.C. and Arlington; problems obtaining financing (which affect the entire region and beyond) and problems at WSSC, which one source described as “a mess.”

But the two words I hear from the development industry describing our county the most are “uncertainty” and “risk.” They do not trust the county’s leadership to avoid intervening in the economics of their projects and investments. They cite multiple laws to regulate employment of building service employees (one of them lead-sponsored by Riemer), a new law on radon testing, a new law on building energy performance standards, multiple temporary rent control ordinances and the brand-new all-electric building law that delegates writing of regulations to County Executive Marc Elrich, arguably the biggest skeptic of new housing in the region. They took notice when Elrich said two years ago that the county did not need developers to build housing. And they are closely watching the county’s potential passage of permanent rent control.

The industry’s view is that the county is simultaneously taking measures to limit their revenues and increase their costs, thereby increasing the risk level of their projects. Outside of Bethesda, where high revenues per square foot may justify higher risk, there is an increasing reluctance to proceed with projects elsewhere in the county unless they draw public subsidies. They ask, “Why should I bear more risk if I can get an equal or better return elsewhere for less risk?”

You may agree with them or not, but housing providers have options to build projects in many other jurisdictions across the region that share Montgomery County’s strengths as a market. If this view becomes more entrenched, then all of the plans and bills we pass will be irrelevant. The industry will simply avoid us. If we care about housing, we cannot let that happen.

And so the totality of our story on housing is a contradiction. We say we want more housing and we pass numerous legislative, planning and budgetary measures to get it. But our repeated interventions in the economics of development create uncertainty that deters actual construction. The new council has to resolve this contradiction in a favorable way. Otherwise, we will continue to struggle and real progress on housing will be elusive.