By Adam Pagnucco.

Unless your goal is to stop construction of new housing, rent control of the kind practiced in Takoma Park is not the answer to Montgomery County’s housing challenges. So what is the answer? It’s time to look at the nature of some of the county’s biggest housing problems, which include the following.

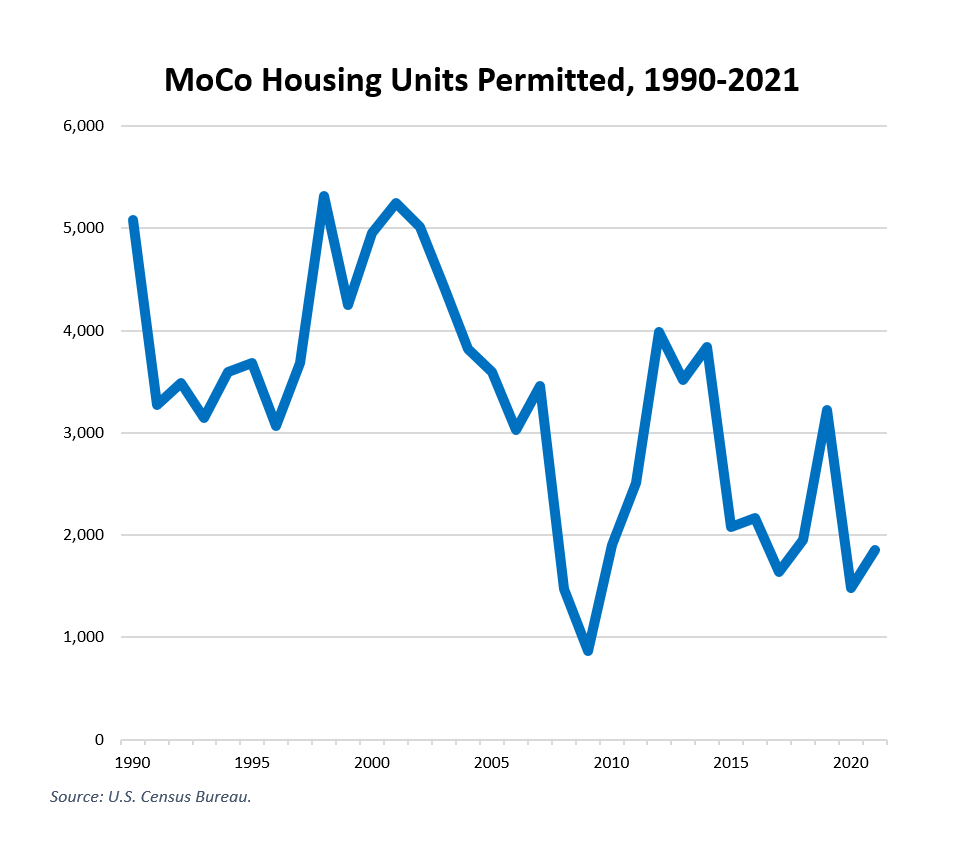

We are building less housing than we used to.

The chart below shows housing units permitted in MoCo from 1990 to 2021. From 1990 through 2007, we permitted an average 4,006 units per year. We now struggle to produce even half of those units annually.

It’s not just us. The Washington-Arlington-Alexandria metro area regularly permitted over 35,000 units per year in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The region now permits 25,000-27,000 units a year. Slowing construction is a regional issue that handicaps many local jurisdictions here.

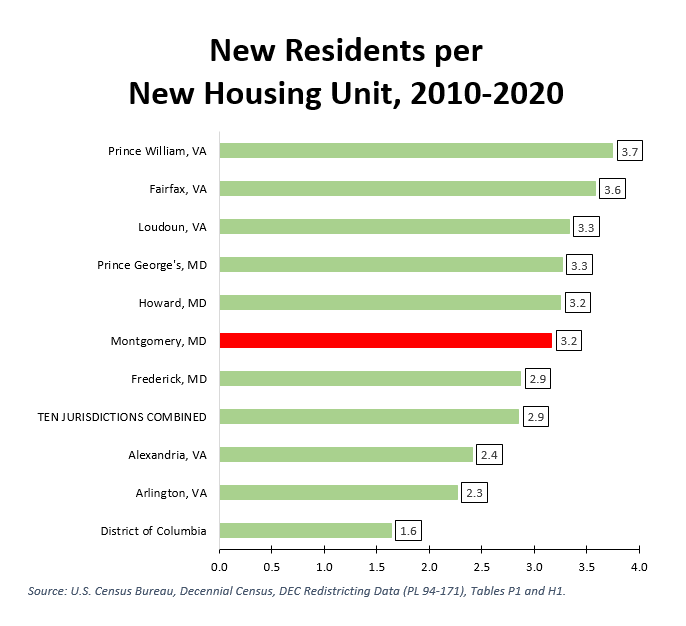

We are failing to build enough housing to keep up with population growth.

On average, the Washington metro area has 2.6 people per housing unit. So if a new unit were built for every 2.6 new residents, supply and demand should be balanced. That’s not the case in MoCo. According to the decennial census, MoCo added 90,284 residents between 2010 and 2020 while adding 28,518 housing units. That’s an increase of 3.2 residents for each new unit – not enough to keep up with demand. The effect of that imbalance is that residents compete against each other to bid up the price of housing, resulting in both home price increases and rent hikes.

Again, it’s not just us. The chart below shows the number of new residents per new unit for the ten largest jurisdictions in the region between 2010 and 2020. If a new unit is needed for every 2.6 new residents, then only D.C., Arlington and Alexandria are keeping pace with their population growth. The other jurisdictions are exacerbating the region’s housing shortage.

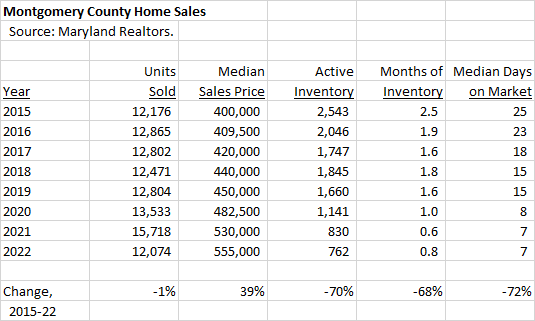

The inventory of housing available for sale has been falling relative to demand.

The table below shows key stats from the Maryland Association of Realtors for MoCo’s home sales market from 2015 through 2022. The number of units sold has increased through 2021 but then dropped last year. The active inventory of homes available for sale has dropped sharply. So has the number of months of inventory available and the median days on market. The result has been soaring sales prices. Once again, supply is an issue.

What does this have to do with rents? Because it’s harder to find housing to buy at affordable prices, potential homeowners are more likely to be pushed into the rental market, thereby driving up rents. Markets for rental housing and owner-occupied housing are linked, illustrating a central truth – the county needs more housing of all kinds, owner-occupied as well as rentals.

And what happens if you move? Good luck with that. The realtors’ data shows similar trends in the rest of the state. Once again, it’s a regional issue.

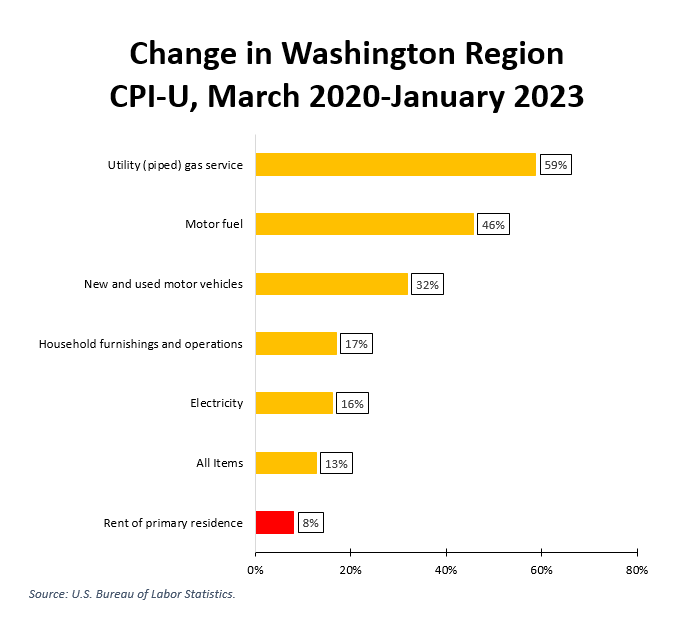

Rental housing is suffering from cost-push inflation.

The pandemic, the war in Ukraine and related supply issues have caused inflation to ignite across the global economy. The Washington region’s real estate sector is no exception. The chart below shows the increase in the region’s CPI-U for a number of items relevant to the operation of real estate since March 2020, when the pandemic first hit. Natural gas, motor fuel, electricity, vehicle costs and household furnishings – all operating costs for landlords – are up substantially while rents have risen by 8% in nearly three years.

Regional rents were no doubt affected by temporary rent controls in D.C. and Montgomery County as well as widespread prohibitions on evictions. But with their operating costs spiking after a prolonged de facto limit on rent increases, it’s predictable that landlords would pass at least some of them on to tenants after eating them for more than two years. This factor will continue to be an issue as long as inflation persists in the world economy.

MoCo’s slow job growth may be impacting developer decisions to build housing.

One of the most-read posts in the history of Seventh State was this one on the lack of development in White Flint. The area was master planned for tons of new housing and other development a decade ago, but only some of it (chiefly around Pike and Rose) materialized. In interviews with the county’s planning department, White Flint developers cited slow job growth as a big reason why they had not proceeded with new housing projects. Among other things, the planners’ report stated:

All developers interviewed cited Montgomery County’s limited job growth as a fundamental challenge to continued construction in the Pike District. Low levels of new jobs limit the number of new families seeking to occupy units in the county (household formation), decreasing demand for new development.

That was two years ago and only applied to one area in the county, although one once thought to be a prime building location. Is this issue affecting housing construction in the rest of the county?

What do the above factors have in common? Aside from recent inflationary pressures, they relate to the supply side of the housing market. We are not building enough housing to keep up with demand. Neither is most of the rest of the region. That failure puts upward pressure on both home prices and rents.

The county council recognizes the need for new housing and has done several things to promote it, including liberalizing restrictions on accessory dwelling units, ending the county’s housing moratoriums, cutting impact taxes, passing tax abatements for development near Metro stations, passing Thrive 2050 and approving numerous new master plans. The council did so in many cases over the opposition of the county executive. Some of these steps have been taken in the last couple years and so have not had time to affect the pipeline of housing, although cumulatively they should eventually have at least some effect – providing of course that rent control is not installed.

In contrast, the evidence from Takoma Park and St. Paul, Minnesota is that rent control – particularly when applied to new construction – kills the expansion of housing supply among its many other negative impacts. Its adoption would make the county’s housing shortage far worse and nullify every measure the council has so far implemented to grow our housing base.

The choice of whether to impose rent control is one of the most important decisions the new county council will make. They can choose a policy with a long record of ruinous failure, abandoned even by Vietnamese Communists. Or they can choose the path of increasing the supply of housing to meet the demand for housing, the only option that can remedy our housing problems over the long run.

The evidence is clear. Now which path will they choose?