By Adam Pagnucco.

If there is a sacred cow in MoCo politics other than public schools, it’s probably the Agricultural Reserve. Its creation was listed by my panel of county historians as one of the five most important events in MoCo since the 1960s. Here is how the county’s planning department describes the Ag Reserve.

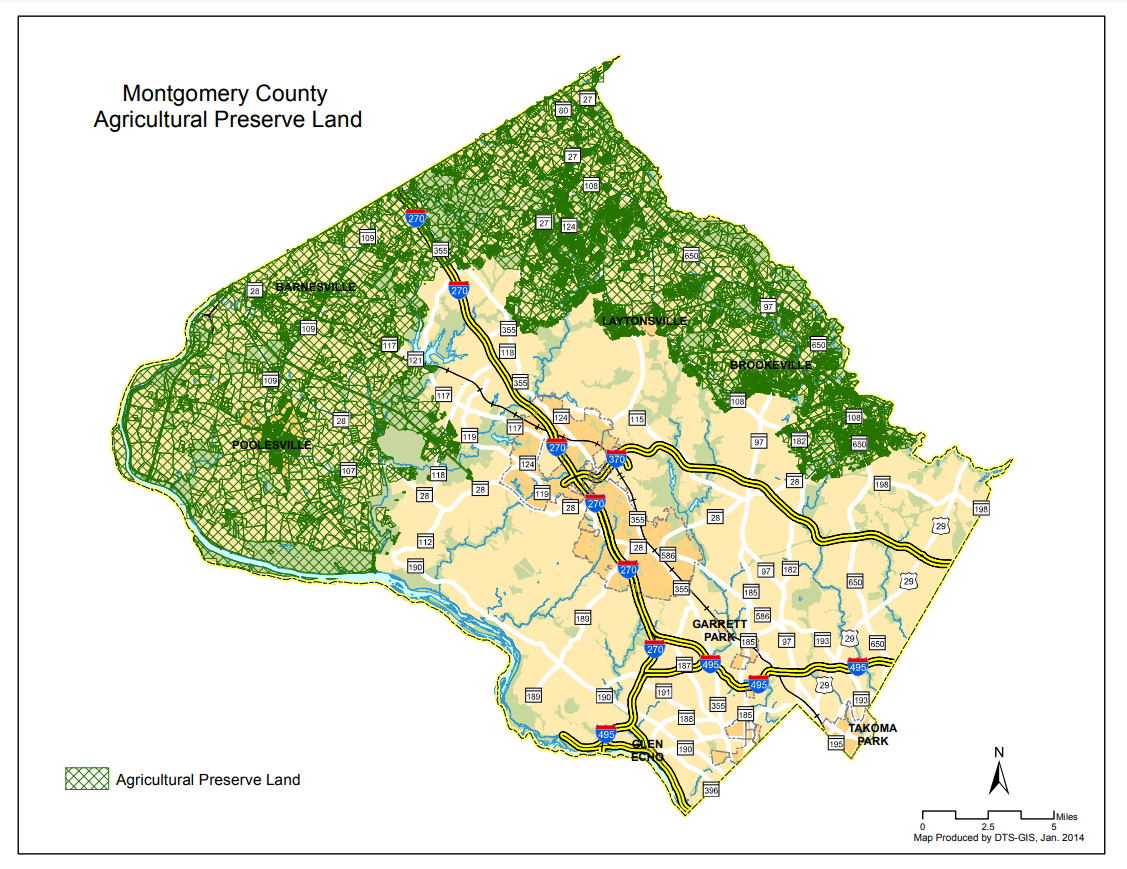

In 1980, the Montgomery County Council made one of the most significant land-use decisions in county history by creating what we call the Agricultural Reserve. Heralded as one of the best examples of land conservation policies in the country, the Agricultural Reserve encompasses 93,000 acres – almost a third of the county’s land resources – along the county’s northern, western, and eastern borders.

The Agricultural Reserve and its accompanying Master Plan and zoning elements were designed to protect farmland and agriculture. Along with a sustained commitment to agriculture through the county’s Office of Agriculture, the combination of tools helps retain more than 500 farms that contribute millions of dollars to Montgomery County’s annual economy. This is a notable achievement in an area so close to the nation’s capital, where development pressure remains perpetual and intense.

Preservation of the Ag Reserve is so ingrained in county politics that while there are occasional debates about its appropriate uses, almost no one publicly questions the virtue of its existence. That is, until now. And those questions are now arising from within the county council building itself.

The triggering event was the introduction of Zoning Text Amendment 23-09, lead-sponsored by Council Member Natali Fani-Gonzalez, which would allow limited incidental outdoor stays on some farms in the Ag Reserve. The outdoor stays must be part of education and tourism activities, cannot be in sleeping quarters with cooking facilities and cannot extend beyond 4 days a week among other restrictions. Fani-Gonzalez views the ordinance as a positive thing for farms and agritourism. Some folks will disagree. Such is the course of legislative debate in MoCo.

Now we come to the county council’s Office of Legislative Oversight (OLO), which issues racial equity and social justice statements on legislation. OLO could have issued a narrowly tailored analysis looking at the racial equity impacts, if any, of the ZTA. Instead, it issued a broad takedown of the history and purpose of the Ag Reserve, claiming that its establishment “cemented racial segregation as many Black rural communities within it had been depopulated and its zoning requirements prohibit the development of new affordable multi-family housing units.” It ultimately concluded that the ZTA “will have little to no impact on existing racial and social inequities in the County.”

I have never seen a critique of the Ag Reserve quite like this, and especially not from an office of county government. And let’s bear in mind that the primary advocacy organization for the Ag Reserve, the Montgomery Countryside Alliance, has been funded with county tax dollars. That’s a sign of how high a priority the county places on having an Ag Reserve.

Following is an extended excerpt from OLO’s racial equity and social justice statement on the ZTA. Is OLO right that the Ag Reserve cements racial segregation? Or did the office go too far in attacking one of the county’s most notable achievements of the last 60 years? Readers, you make the call.

*****

RACIAL INEQUITIES IN THE AGRICULTURE RESERVE AND AGRICULTURE BUSINESSES

Understanding the RESJ impact of ZTA 23-09 requires understanding the local history of racial inequity in land use that has fostered racial disparities in the Agriculture Reserve and agritourism businesses. Indigenous peoples affiliated with the Piscataway Conoy Tribal Nation lived in the area known as Montgomery County when Europeans first colonized the area in the 1600’s. In 1688, the earliest colonial land grants began to carve up Indigenous land into large land tracts that formed the spatial basis for a plantation economy reliant upon enslaved African labor that lasted until the Civil War.

Before the Civil War and Post-Emancipation, Black people accounted for about a third of the County’s population and White people accounted for the remainder. Despite the challenges faced post-Reconstruction, African Americans developed 40 Black settlements across the County. As observed by Nspiregreen in the Draft Plan of Thrive 2050:

After the Civil War, African Americans suffered from all forms of discrimination (social, housing, education, employment, commerce, health, etc.). The resulting alienation led to the creation of self-reliant kinship communities in many parts of Montgomery County in the late 19th century. A significant part of history of racial injustice and discrimination suffered by African Americans includes the formation and subsequent decline (in some cases, destruction) of kinship communities in the early 20th century.

Overtime, these communities suffered from a lack of public investment in infrastructure such as new roads, sewer and water, schools, health clinics, and other public amenities and services needed to be viable places to live. Some communities suffered the devasting impacts of urban renewal policies of the 1960’s. Others faced pressure to sell their houses or farms to developers for housing subdivisions. These communities declined because an accumulation of racially motivated actions paired with social, political, and economic circumstances. Very few of these communities that survived in some way include Ken-Gar in Kensington, Laytonsville in Silver Spring, River Road in Bethesda, Scotland in Potomac, Stewartown in Gaithersburg, and Tobytown in Travilah.

The decline in Black settlements in the early 20th century occurred due to White suburbanization of the County. Between 1900 and 1960, as the County shifted from rural to suburban, the population grew 11-fold from 30,451 to 340,928 residents. With exclusionary zoning, redlining, racial covenants, and racial steering, almost all the population growth in the County occurred exclusively among White households. Between 1940 and 1960 the White population increased more than four-fold from 74,986 to 327,663 residents while the Black population only increased from 8,926 to 13,265 residents. As such, the Black share of County constituents diminished from a third to only three percent.

Overall, Black people were systemically excluded from benefiting from the County’s exponential growth and increasing property values resulting from suburbanization. The legacy of discriminatory policies and land use decisions led to the decline in the Black share of the County’s population and reinforced racial segregation. Within this context the Agriculture Reserve was enacted in 1980 and cemented racial segregation as many Black rural communities within it had been depopulated and its zoning requirements prohibit the development of new affordable multi-family housing units. As a result, few Black people benefited as farmers and agrotourism business owners in the Agriculture Reserve, despite Black people historically accounting for a third of the County’s population before suburbanization.

Data on farm operators and producers shows that Black, Indigenous and Other People of Color (BIPOC) are underrepresented as farm producers and potential agritourism operators in the Agriculture Reserve. Approximately 70 percent of the 93,000-acre Agriculture Reserve is used for farm operations. In 2017, there were 558 farms in the County with a total of 1,026 farm producers.

Among Montgomery County farm producers, 93 percent were White, 3 percent were Latinx, 3 percent were multiracial, 2 percent were Black, 2 percent were Asian and less than 1 percent were Indigenous. Yet, White people currently account for 42 percent of the County’s population, Latinx people account for 20 percent, Black people account for 19 percent, and Asian people account for 15 percent. Thus, White people are over-represented among farm producers and BIPOC are under-represented among farm producers compared to their relative shares of the County’s population.