By Adam Pagnucco.

Part One outlined the basic financial characteristics of WAMU. Part Two explained how corporate underwriting, WAMU’s second largest revenue source, collapsed after 2019. This was partially replaced by increased contributions of goods and services by WAMU’s owner, American University (AU). Part Three looked at WAMU’s efforts to control costs. Today, let’s look at the balance between revenues and expenses.

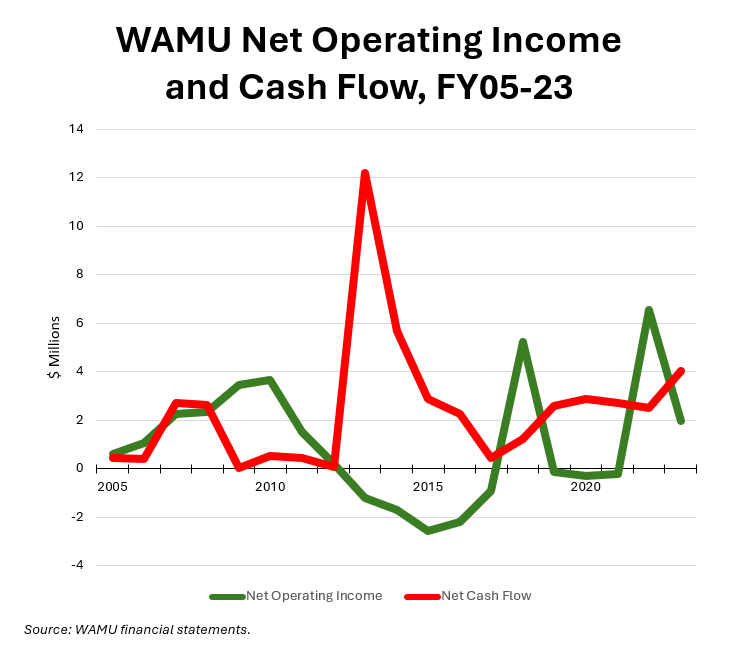

The chart below shows two measures of financial performance – net operating income (operating revenues minus expenses) and net cash flow – from FY05 through FY23.

Net cash flow has been positive for all 19 years in the series. Any organization – especially a media organization – would be happy with that.

Net operating income is more complicated. It was positive from FY05 through FY12. That’s impressive since the later part of this period included the Great Recession. But then it turned negative in eight of the next nine years. It may not be a coincidence that WAMU signed a lease with AU in 2012 and took out a loan from AU the next year. Those two items together impose over $2 million a year in costs on WAMU.

However, WAMU rebounded after COVID, reporting $6.6 million in net operating income in FY22 and $2 million in FY23. The FY22 result is the best in the series. It comes with a caveat – it is partially due to WAMU’s booking of a forgiven federal $2.6 million Paycheck Protection Program loan as grant revenue. Still, FY22 and FY23 were good years and do not indicate urgent weakness that demanded layoffs. Clearly, something else was going on.

When looking at WAMU’s finances, we should never forget this statement that appears near the top of every financial report: “WAMU is dependent for its continued operations on the financial support of the University.” AU subsidizes WAMU in three ways that are discussed in its reports: donated goods and services, a zero-interest loan and allocated endowment funding. Of the three, donated goods and services may be the largest.

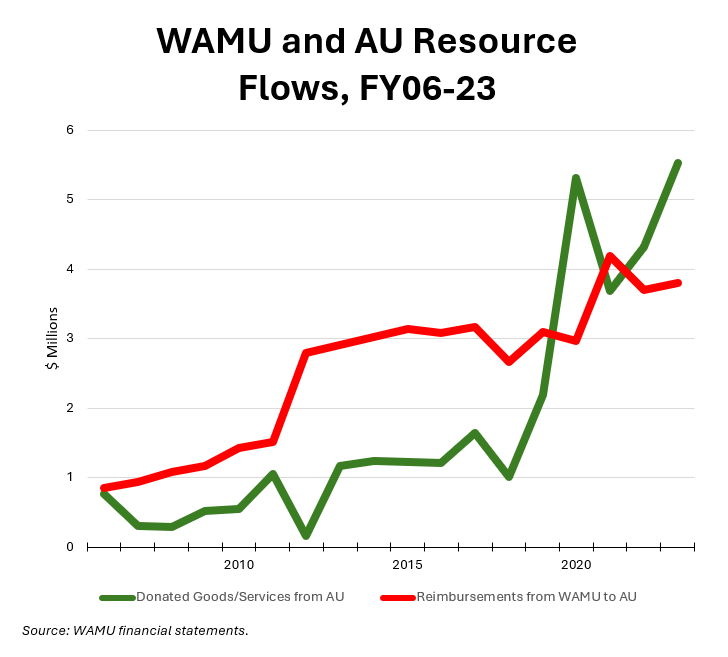

In Part Two, we saw that AU’s donations of goods and services were rising in both absolute terms and as a percentage of WAMU’s revenue. The financial reports show that some of these donations are reimbursed by WAMU but the two amounts are not equal. The chart below shows donations from AU and reimbursements from WAMU to AU since FY06.

The relationship between donations from AU and reimbursements to AU has changed over time. From FY06 through FY19, reimbursements exceeded donations in every year. That means AU had a net positive resource flow from WAMU during this period. However, in three of the last four years, reimbursements fell short of donations. AU was now putting in more resources than it received in return. That no doubt contributed to WAMU’s positive financial results in FY22 and FY23.

The above conforms to what we learned in Part Two: WAMU has been steadily increasing its dependence on AU over time. Why does that matter? AU is facing a shortfall this year of more than $30 million as reported by its student newspaper in October and February. In December, AU hired a consultant that has been known to recommend cuts at other universities. WAMU is a small part of AU’s empire and could easily be seen by any consultant as tangential to the university’s missions of obtaining research funding and educating students. A smaller WAMU could be expected to consume less support from AU, thereby freeing up those resources for other activities.

And so that raises a question. Is WAMU management’s promise to focus on audio, which has been called into question by its current and former staff, just spin covering for simple cost cutting? If so, there is reason to be skeptical that this will work.

Let’s recall that WAMU’s two largest revenue streams are contributions from individuals and organizations and corporate underwriting. Both have declined in recent years with underwriting falling by nearly half since FY19. How will individuals and organizations react to a smaller, less localized WAMU? Contributors may feel like they are getting less value in return for their support. As for corporate underwriters, at least some may see their payments as tantamount to advertising. If they believe a diminished WAMU will have a smaller audience, they may cut back their underwriting even more than they have. WAMU’s cost cutting may therefore endanger its largest revenue sources over the long term, possibly prompting even more cuts – if that’s even possible without closing the station.

WAMU must show its supporters that its new strategy to “deepen engagement with Washingtonians” will actually work, both journalistically and financially. If it can’t, one wonders if the most recent round of layoffs will be the last.