By Adam Pagnucco.

Last week, the county council passed an FY26 operating budget with robust spending increases and no tax hikes. How did they do it? In part, they relied on an accounting maneuver involving a fund used to pay retiree health care benefits called OPEB (other post-employment benefits). What is OPEB? And why does the county set aside money to pay for it?

The story of the county’s OPEB funds begins before the Great Recession. In those days, state and local governments paid the costs of retiree health care benefits on a pay-as-you-go basis. The costs were growing rapidly and started to burden government budgets. So in 2008, the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) told state and local governments that they had to begin accounting for OPEB and prefunding it in the same way that they do for pension benefits. Each government would have to publish how much it saved, how much it owed on an actuarial basis and its OPEB funding ratio in its comprehensive annual financial reports. These stats could be viewed by the public and – ominously – the credit ratings agencies.

MoCo had a plan to ramp up OPEB prefunding, but the Great Recession hit and the county couldn’t contribute to OPEB for a couple years. Originally, each of the county’s four major agencies (county government, MCPS, the college and Park and Planning) had separate OPEB funds that they each controlled. During the recession, the county government placed all of them except for Park and Planning into a consolidated trust. Currently, the county makes two kinds of OPEB expenditures on behalf of the agencies: payments to meet current retiree health care expenses and prefunding payments intended to build up the fund balances.

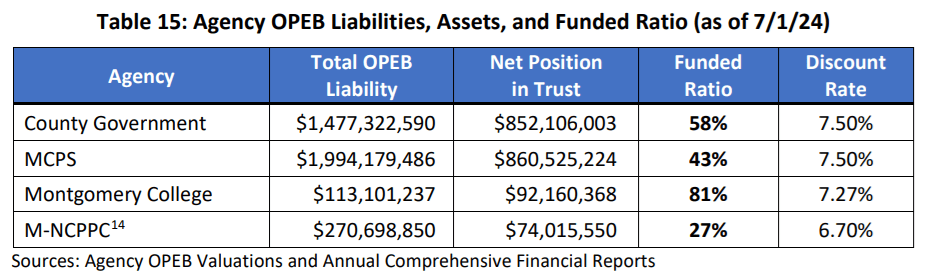

Starting from zero, the county has made a lot of progress on its funding ratios for OPEB. A recent council staff memo shows those ratios as of 7/1/24.

Pension funds are regarded as generally healthy if they are at least 80% funded. The college’s funding ratio hits that level but the other agencies do not. To be fair to MoCo, OPEB funding ratios are all over the place in other jurisdictions. The State of Maryland has a horrible 4.3% OPEB funding ratio. The District of Columbia has a 108.2% OPEB funding ratio.

Combining the four agency funds, the county has built a total fund balance of nearly $1.9 billion. One thing I occasionally hear from the executive branch and some outside groups seeking county money is: why do we need to fence off that much cash? County Executive Marc Elrich would like to tap it and has proposed doing so in the past. But the council often resists it.

Two years ago, I interviewed Council Members Andrew Friedson and Kate Stewart about the budget and other matters in a public forum. (Stewart is this year’s council president). Here is what Stewart said about OPEB at that time.

*****

And we’re looking at – Andrew mentioned OPEB, the benefits that we provide to our retirees. There’s a lot of conversation, again from across the street, on how that should be used and whether or not that is a source of funding that we could actually take money out of. I think it’s safe to say that both of us here feel really strongly that is not something that we should be taking money out of to fund ongoing expenses in our government. Those are really important funds and we’re working right now on updating the policy, the county policy for OPEB to make sure that it is sustainable. Because there are promises that we made to people who worked for our government and to our retirees and we have to keep those promises as we have to be responsible. That is top of line for me as we’re looking forward.

*****

Nevertheless, the county has diverted OPEB prefunding money more than once. After a $90 million diversion in 2019 (against which Friedson cast the sole dissenting vote), Moody’s called the maneuver a “credit negative.” Moody’s wrote:

*****

On April 30, Montgomery County, MD (Aaa stable) lowered its contribution toward prefunding employee retiree healthcare benefits in order maintain progress toward its fiscal 2020 reserve target, the second consecutive year it has done so. The reduction in prefunding for retiree healthcare, also known as other post-employment benefits (OPEBs), is credit negative because the county will accumulate assets more slowly and thus carry higher unfunded liabilities. At the same time, the county’s past build-up of OPEB assets has provided it with budget flexibility to lower contributions in favor of hitting reserve targets. This flexibility would not be available if the county had no OPEB assets and was instead paying for these benefits directly from its budget, an approach called “pay-as-you-go” funding.

*****

Despite the displeasure from Moody’s, the agency did not downgrade the county’s bonds.

What happened this year? The council did not want to go much below MCPS’s operating budget request but it also did not want to raise taxes as the county executive recommended. Instead, the council diverted $50 million of OPEB money (two equal tranches in FY25 and FY25) that had been intended for prefunding and used it to pay MCPS’s current retiree health benefits. This had two virtues. First, the OPEB money is regarded as a one-time payment and thus does not go into the county’s maintenance of effort base. Second, because MCPS could use this prefunding money to pay current benefits, it could use the money it would have used for those benefits for other purposes. The teachers union supported it. The police union opposed it, but later retracted its opposition.

So what’s the problem? I see three of them.

First, because prefunding money was reduced, the county’s MCPS OPEB fund will – as Moody’s stated above – “accumulate assets more slowly and thus carry higher unfunded liabilities.” Combined with the inevitable investment losses caused by President Donald Trump’s stock market crash, this will dirty up the county’s financial statements.

Second, Elrich – who favored using OPEB money for current expenses rather than prefunding even before the council did so – will be encouraged to propose doing so again. Will this year’s temporary fix become a repeated practice?

Third and most importantly, what will the ratings agencies think of this? Moody’s just downgraded the District of Columbia and the State of Maryland. (To be fair to the county council, the Maryland downgrade occurred after its OPEB proposal became public.) MoCo is subject to the same federal government stresses that caused the D.C. and state downgrades, so if the county is perceived on top of that to be playing fast and loose with OPEB, what then? Also worth noting is that while county leaders have demonstrated repeated willingness to raise taxes in the past – a practice usually viewed favorably by ratings agencies – the county has far fewer taxing options than the state. For example, the state does not allow MoCo to levy a general sales tax or a corporate income tax. The county has fewer ways to escape federal devastation than either the state government or D.C. – a fact of which the ratings agencies are no doubt aware.

A loss of MoCo’s bond rating by any of the major credit agencies would be a gigantic event since the county has enjoyed AAA ratings every year since 1973. If county leaders lose our bond rating in part because of their fiscal practices, there will be nowhere to run and nowhere to hide. They will go down as the worst leaders in county history.

Will the county pay a price for this OPEB maneuver? I can’t say since the wild ride of the Trump economy, nationally and locally, is just getting started. But county leaders must buckle down and get serious about spending. If not, dark consequences may await.