By Adam Pagnucco.

As Montgomery County’s state legislators consider a bill that would enable ranked choice voting in the county, they should consider the fact that their Department of Legislative Services estimates that it would cost the state and local governments millions of dollars to implement. What exactly would we get for those millions?

The state legislation would not directly create ranked choice elections but it would enable the county council to design and implement them. It would also enable the council to set up approval voting, a less widely used system that allows voters to vote for multiple candidates without ranking them. It was passed without opposition by the county’s delegates but it still must make it past the county’s senators as well as the General Assembly.

The bill’s fiscal note contains cost estimates for both ranked choice voting and approval voting for the state as well as the county. For the state, the fiscal note estimates that ranked choice voting would cost between $242,000 and $293,000 annually from FY24 through FY28. It states that “The bill is not expected to materially affect State finances if an approval voting system is adopted.”

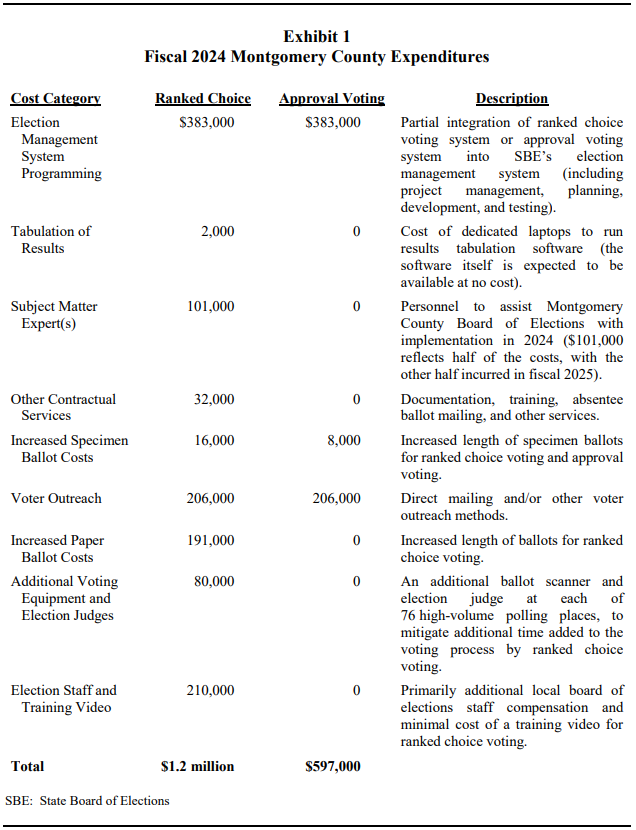

For the county, the fiscal note presents the cost estimates below for FY24.

That’s just the beginning. For future years, the fiscal statement says:

Costs are incurred in future years but at a reduced overall level. For a ranked choice voting system, Montgomery County expenditures increase by approximately $750,000 in fiscal 2025, $704,000 in fiscal 2026, $648,000 in fiscal 2027, and $483,000 in fiscal 2028. For an approval voting system, Montgomery County expenditures increase by approximately $214,000 in fiscal 2025 through 2027 and by $8,000 in fiscal 2028.

One thing that unites supporters and opponents of ranked choice voting is their reliance on speculation. They make many allegations but provide little evidence. Examples include this column in Maryland Matters from supporters and this condemnation by the Montgomery County Republican Party.

Because the debate over ranked choice is so filled with anecdote, ideology and evidence-free assertions, I assembled a database of 1,120 actual ranked choice elections across the United States over the last twenty years and crunched their results in a series I published in January. I found that ranked choice elections produced a different result from traditional elections just two percent of the time. There are two reasons. First, ranked choice is not triggered 85% of the time because there are no opponent(s) or because there are not enough candidates to utilize it. (For example, ranked choice is not needed when two candidates run for one seat.) Second, when ranked choice is utilized, the first-round leader(s) win in the end 85% of the time. As a result, in the dataset’s 1,120 elections, a different winner from the first-round leader emerged under ranked choice just 25 times.

The data indicates that the predictions of sweeping positive change by supporters and doom by opponents are both overblown. If a new methodology produces the same result as an old methodology, it is neither vastly superior nor vastly inferior. In fact, it’s not that different at all.

But as we have seen from the fiscal note above, it does cost millions of dollars over time. And the fiscal note does not address any delays in vote counting that might occur because of ranked choice. Twenty-two elections in my dataset went for 10 rounds of counting or more. One went for 34 rounds and the first round winner never trailed and ultimately won.

The meaningful policy debate here is not whether ranked choice is good or bad. It’s whether the minimal changes it delivers are worth millions of dollars in cost and any possible ballot counting delays. Former Council Member Phil Andrews once advised his colleagues to “guard well” the public treasury and to ask whether public expenditures were “the next best use of scarce tax dollars.”

That is great advice to the General Assembly on this issue.