By Adam Pagnucco.

In my five-part series on teacher salaries and my dissection of MCPS’s fund balance, I have studied the growing surpluses available to MCPS management. But it turns out that MCPS is not alone, and my original source for that is… MCPS.

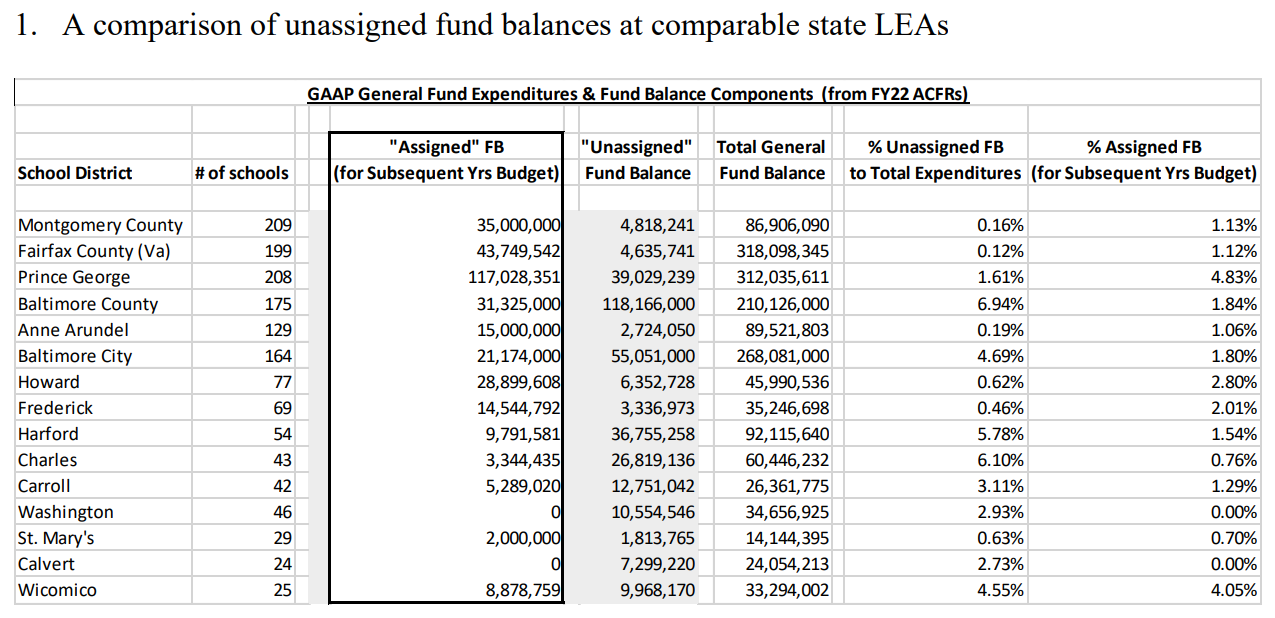

During the recent budget deliberations, the county council’s Education and Culture Committee asked MCPS for the fund balances possessed by other nearby school districts. The table below shows MCPS’s reply. Among the substantial general fund balances reported by neighboring school systems in FY22 were $318 million in Fairfax, $312 million in Prince George’s, $268 million in Baltimore City and $210 million in Baltimore County. These are all much larger than the $87 million reported by MCPS. Harford County, which has a much smaller system than MCPS, reported having $92 million.

Fund balance information can be found in the comprehensive annual financial reports (CAFRs) published by school systems. Since CAFRs are regulated by the Governmental Accounting Standards Board, they are useful standardized information sources.

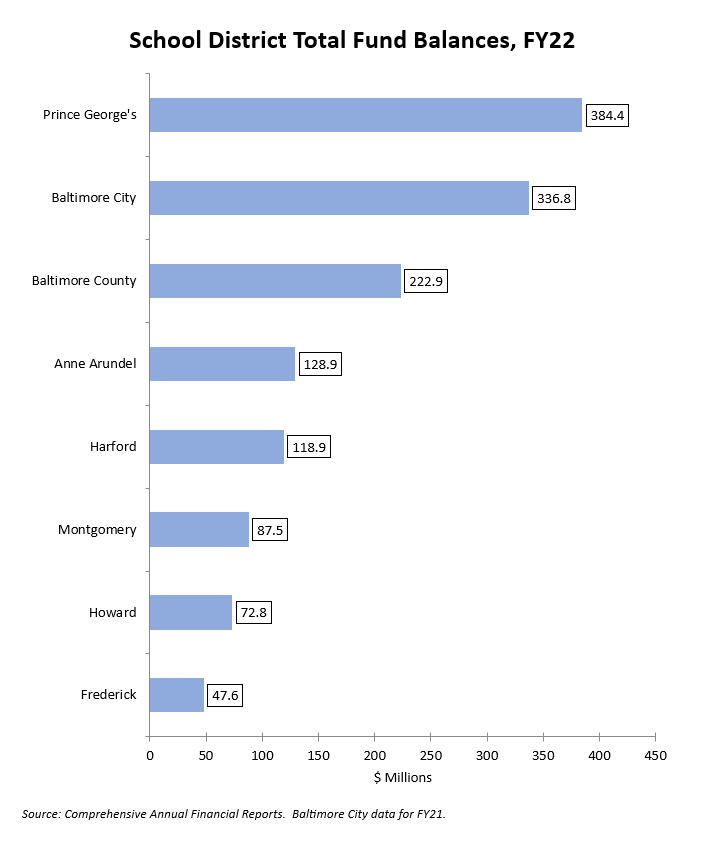

The chart below shows the total fund balances in FY22 for Maryland’s eight largest school systems. These include both general funds and other governmental funds. (Baltimore City’s fund balance is reported for FY21 because its FY22 report has not yet been published as of this writing.)

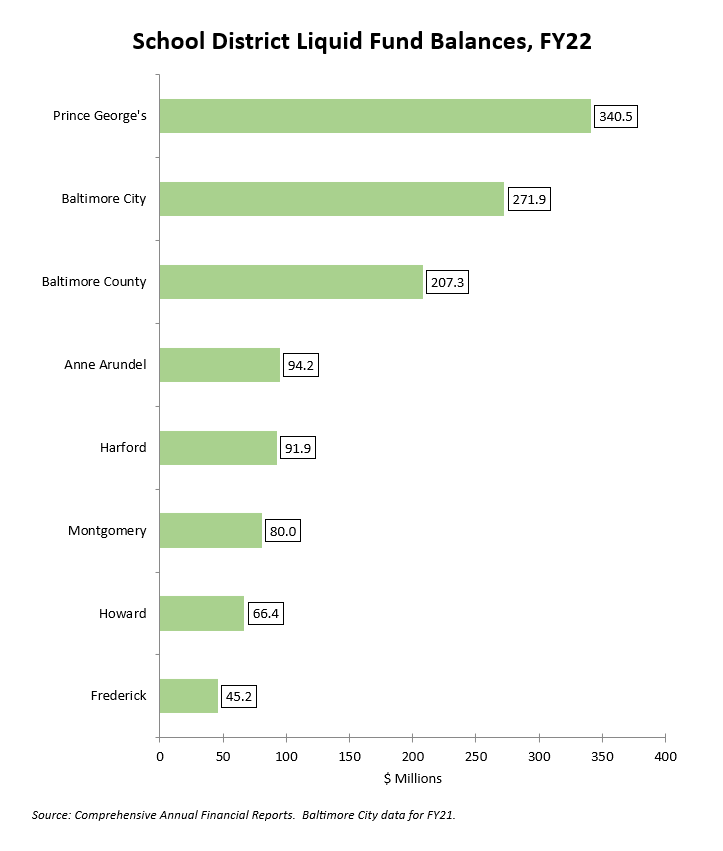

There is a lot of money here but let’s remember that not all of it is liquid. Nonspendable fund balances are mostly inventories and restricted fund balances are dedicated to specific purposes by law or covenant, so they cannot be diverted. The chart below shows “liquid” fund balances, which are defined here as total fund balance minus nonspendable and restricted fund balances.

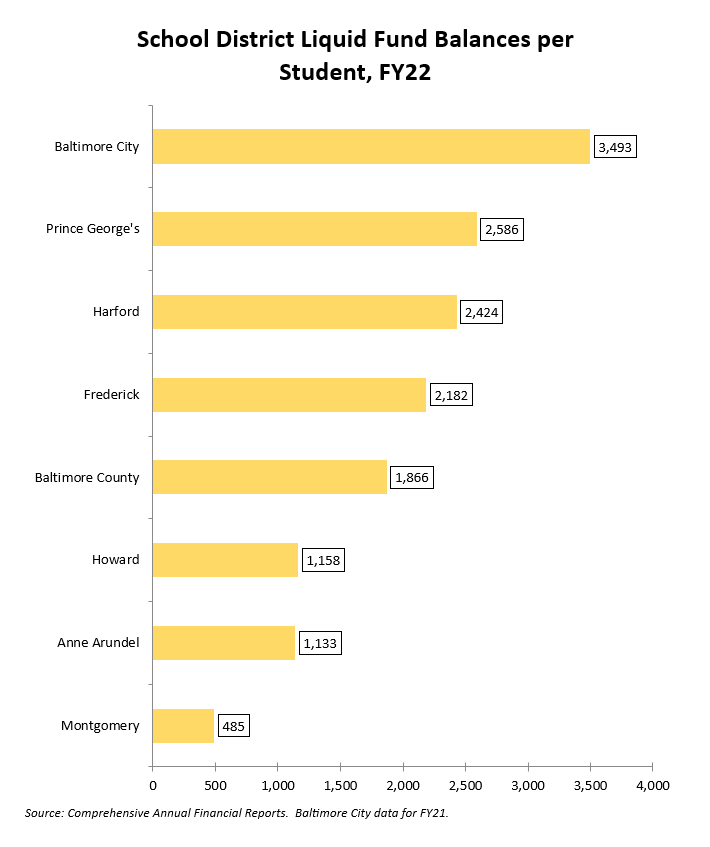

Now let’s look at these liquid fund balances per student using the systems’ most recent enrollments.

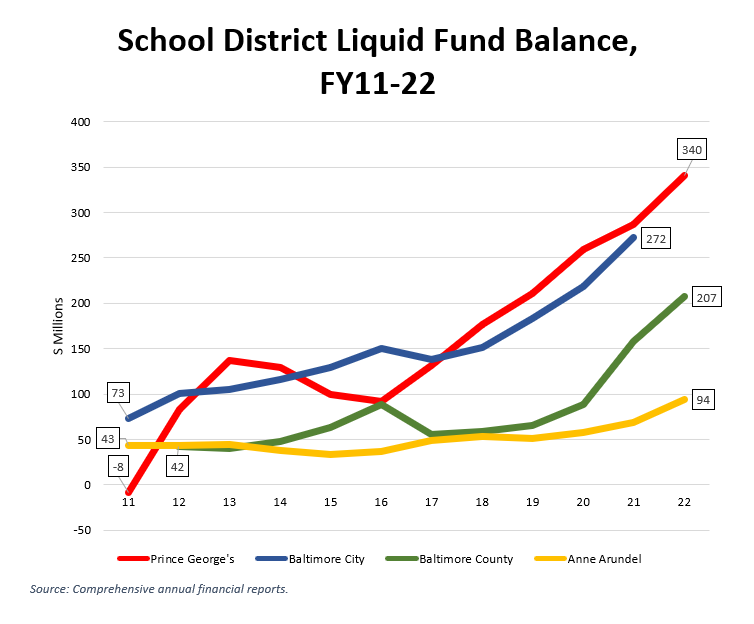

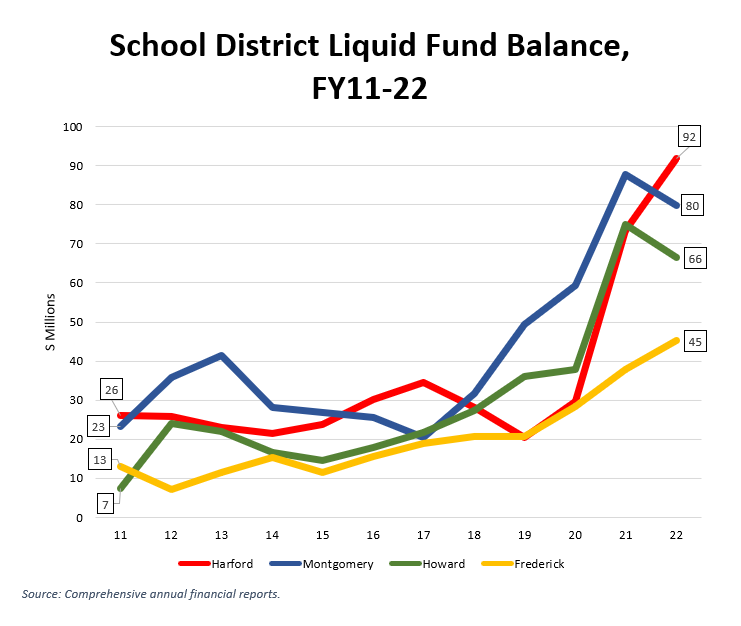

Why are these balances so large? Part of the reason may be because these systems received federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER) money and had not yet disbursed all of it by the end of FY22. That’s understandable. But in fact, many of these school districts have been accumulating growing fund balances for years before the pandemic. That’s less understandable given that all of them have needs and all of them have been receiving increasing budgets to pay for them. The two charts below show the trends in liquid fund balance since FY11, when current category definitions went into effect.

Here is why this is important. The state’s Blueprint program mandates increases in both state and county funding for school systems over the next decade. The leaders of Prince George’s County and Baltimore City are already complaining about their rising mandated contributions. Now it turns out that both of these school districts are sitting on hundreds of millions of dollars. So is Baltimore County. The other districts have tens of millions of dollars in the bank.

One of the big worries in constructing the Blueprint program was that counties would supplant increased state funding and redirect it to other spending. That’s why rising county contributions were mandated. Now it turns out there is a chance that state money could go to the bank instead of the classroom.

The state’s Accountability and Implementation Board must examine this issue. So too must the funders in the General Assembly.