By Adam Pagnucco.

Maryland is a small state but it is an extremely diverse one. Geographically, it extends from the snowy highlands of the west to the crab-filled bay and the ocean in the east. Economically, it contains some of America’s wealthiest communities and some of its poorest. And demographically, its communities range from almost totally White to heavily Black (with large pockets of Latinos and Asians too).

From a political perspective, demographics and county geographies are the most interesting aspects of the state. Let’s start with the counties.

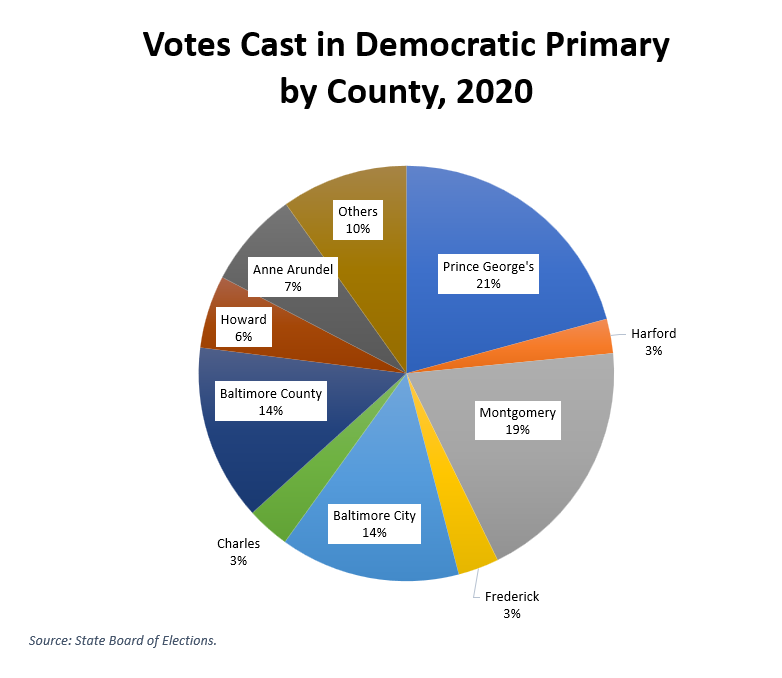

Maryland counties are not equal, at least in terms of population. The state contains two behemoths (Montgomery and Prince George’s counties), three more that are just behind (Baltimore City and Baltimore and Anne Arundel counties), a few mid-size counties (Howard, Frederick, Harford and Charles) and many smaller counties in the east, west and south. Here is how the votes were distributed the last time the state had a Democratic presidential primary in 2020.

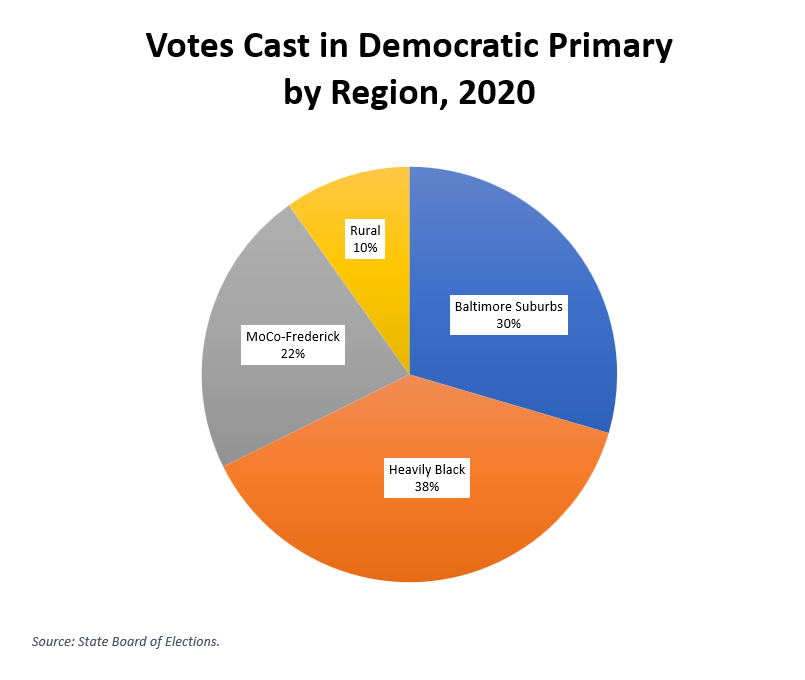

Let’s divvy this up a bit by sorting the counties by region. There are many ways to do this, but in an election featuring two Black candidates (Alsobrooks and Jawando), race must be recognized. The first category will be three heavily Black jurisdictions: Baltimore City and Prince George’s and Charles counties. Next there are the rural jurisdictions (Allegany, Calvert, Caroline, Carroll, Cecil, Dorchester, Garrett, Kent, Queen Anne’s, St. Mary’s, Somerset, Talbot, Wicomico, Worcester and Washington counties), the Baltimore suburbs (Anne Arundel, Baltimore, Harford and Howard counties) and Montgomery/Frederick. Why am I lumping in Frederick with Montgomery? Frederick increasingly resembles Montgomery, has started to trend blue, is not a Baltimore suburb and is not universally rural. Mike Hough may not like it, but we’re grouping it with MoCo in this analysis because there is nowhere else to put it.

Here is how 2020 Democratic primary votes were distributed by region.

Now we can start to divine the paths of the three major U.S. Senate candidates.

Alsobrooks and Jawando need to consolidate their support in the heavily Black jurisdictions. Whoever does that could start with a third or more of the vote. Alsobrooks has an edge here because of her holding office in Prince George’s County for the last dozen years. Next, they need to win a lot of votes from the Baltimore suburbs to go along with pieces of MoCo and maybe Frederick.

Trone will start with the rural areas but they only have 10% of the votes. He needs to add Frederick (which is in his U.S. House district), win MoCo by a lot and get a majority in the Baltimore suburbs. Baltimore TV stations will do quite well in this cycle!

With this order of battle, you can clearly see the collision course between Alsobrooks and Jawando. If Baltimore City and Charles split between them and Jawando can peel off some progressives in Prince George’s County, Alsobrooks will struggle to win – especially when tens of millions of dollars from Trone’s pocket start to dominate TV sets, mailboxes and cellphones.

I could end the series here, but there are more facts that matter. Next, we will learn what happened the last time a Black woman ran for a U.S. Senate seat in Maryland by studying the 2016 campaign of an old Alsobrooks rival: former Congresswoman Donna Edwards.