By Adam Pagnucco.

Part One examined Superintendent Thomas Taylor’s rationale for his huge capital budget ask. Part Two quantified huge in historical terms. Part Three looked at the details of Taylor’s budget. Now let’s look at how to pay for it – assuming we want to pay for it.

First, a note on the Capital Improvements Program (CIP), the county government’s six-year capital budget that includes MCPS. It’s COMPLICATED.

The operating budget is a linear thing, with each annual budget succeeding the prior one. It has three major revenue sources – property taxes, income taxes and intergovernmental aid – that together account for more than 80% of the county’s receipts. If you want to understand what drives county operating spending, just look at compensation, which accounts for nearly three-quarters of it. Easy, yeah?

The capital budget is more like a jigsaw puzzle. It is jam-packed with dozens of revenue streams, many of which are dedicated to specific project types and/or agencies. Some of them are quite volatile. All of the revenues have to be forecasted in each of six years – not just one like the operating budget – and they have to be matched against eligible projects which again must be allocated across six years. When I worked at the county council, the staffer who coordinated all of this was Glenn Orlin, a decades-long veteran of county government and a true mathematical genius. I had no idea how he kept it all straight, but he did.

That said, funding for MCPS capital projects is relatively straightforward. There are five major revenue sources for them, none of which MCPS controls. (This is great for Taylor – all he has to do is ask, while it’s the job of the county executive and county council to figure out how to pay for it!) Let’s go over each of the five, starting with the percentage of MCPS capital funding it covered in the FY25-30 CIP.

General Obligation (G.O.) Bonds

28% of MCPS’s FY25-30 capital budget

This is the biggest single source of funding in the county’s capital budget, accounting for 29% of the whole budget and 28% of MCPS’s part of it. G.O. bonds are issued by the county to bond markets and are guaranteed by the full faith and credit of the county government. Since the 1970s, these bonds have earned the highest ratings from every Wall Street credit agency, allowing the county to get the best interest rates of any debtor. If there is a sacred cow in county government, the G.O. bond rating is it.

While revenue from G.O. bonds goes into the capital budget, debt service used to pay them off comes from the operating budget. So over time, the use of G.O. bonds for construction projects will eat up operating money that could otherwise go to schools, public safety, social services and basically everything the county does – especially compensation. That creates caution in their use.

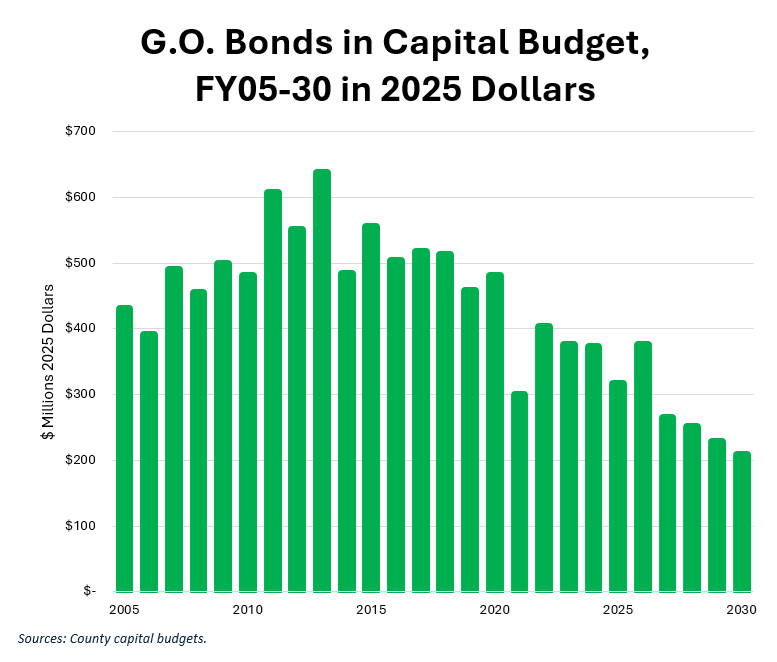

The chart below shows annual use of G.O. bonds in the capital budget in real 2025 dollars. (See Part Two for the methodology of this chart’s construction.)

In real dollars (and also nominal dollars), the use of G.O. bonds peaked in the aftermath of the Great Recession and has mostly fallen since. The increase after the recession was due to the county exploiting rock-bottom interest rates and using construction as a tool to stimulate the economy. However, this practice caused debt service payments to double between 2005 and 2019, causing big headaches for the operating budget. One of the major achievements of County Executive Marc Elrich and the last two county councils has been to curb the growth of debt service by restraining G.O. bond issuances. They may be loath to abandon this practice as renewed growth in debt service will threaten money for union collective bargaining agreements.

The other constraint on the issuance of G.O. Bonds lies in county law. Sec. 20-55 through Sec. 20-58 lays out affordability guidelines for bonds tied to the county’s economy and debt levels. This staff memo lays out the process for how these guidelines are used to set annual G.O. bond issuances. While this process is an internal feature of county government, it exists to prevent wild use of debt from damaging the county’s bond rating, thereby causing higher interest payments. This is a sacred cow that is hardier than most.

Taylor criticized the affordability guidelines in his presentation, saying “County Spending Affordability Guidelines (SAG) sets yearly GO Bond spending caps for all MoCo agencies. Currently SAG at $1.8B or $300M annually, which is not able to meet all county needs. Not even close.” He should be careful what he wishes for, because if the county significantly increases its bond issuances, the resulting spike in debt service will eventually compete with his operating budget requests.

My guess is that the county may mildly increase its use of G.O. bonds for capital projects, but not by any amount that would come close to funding Taylor’s request. And he made this clear – his current huge request is the first of many.

State Aid

24% of MCPS’s FY25-30 capital budget

The state has a large school construction funding program administered by the Interagency Commission on School Construction. The program is largely formula driven, with counties receiving funds for eligible projects determined by set percentages. For example, the state covers 67% of Prince George’s eligible project funding and 91% of Baltimore City project funding. Eligible MoCo projects can get 50% funding from the state, which is tied for the lowest percentage in Maryland. Why are we the lowest? State wealth formulas are responsible, and they regularly drive state aid (especially school money) out of our taxpayers’ pockets to other parts of Maryland.

If Taylor wants more state aid, I guess he could argue that our needs are more acute than other jurisdictions and therefore our aid share should increase. (Good luck making that case in Annapolis, which believes we are filthy rich!) Or he could argue that total school construction funding should increase and we should get our fair share of it. There are two problems with that: a possible recession and huge operating money obligations under the state’s Blueprint program for public schools.

See why this is unlikely to happen in a big way?

Look folks, the state does not bail out MoCo. It’s the other way around. MoCo taxpayers regularly bail out the state, just like we did with this year’s income tax increase, and the Lords of Annapolis will make sure that we do it again. Real money will have to come from elsewhere.

We will find out where next.