By Adam Pagnucco.

Council Member Will Jawando is running for county executive in the county’s public financing program, which requires candidates to rely on contributions from individuals of $500 or less. In a recent statement, Jawando said, “We don’t need to rely on big money or special interests to build a winning campaign. We’re powered by people, and we’re ready to fight for them every day.”

And yet, Jawando’s U.S. Senate campaign account paid $115,000 to an organization that later endorsed him for executive. And that organization has a history of running independent efforts to elect Maryland candidates it supports.

Is this ethical? Is it legal?

The organization in question is the Working Families Party (WFP), a progressive group founded in New York in 1998. The group sometimes runs candidates on its own party line and other times endorses Democrats. Among the candidates it has supported are U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders (for president), New York Attorney General Letitia James, Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson, former New York City Mayor Bill DeBlasio and incoming New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani.

The group has twice launched independent expenditure committees to help Maryland candidates. In 2018, the Working Families Party National IE Committee spent $121,000 to help Democratic gubernatorial candidate Ben Jealous in his unsuccessful challenge against Governor Larry Hogan. And in 2024-25, the Working Families Party PAC spent $10,136 to help elect Prince George’s County Executive Aisha Braveboy and two Prince George’s County school board members. The latter committee reported $1.26 million in contributions, indicating that it had the capacity to do more. It remains an active committee according to the Maryland State Board of Elections at this writing.

Prior to running for county executive, Jawando ran for U.S. Senate in a primary featuring Prince George’s County Executive Angela Alsobrooks and Congressman David Trone. He dropped out of the race in October 2023 and reported a cash balance of $163,531 at the end of that year. Jawando used some of that money to found his Will of the People federal PAC, which supported Democratic candidates around the country in the 2024 elections. His U.S. Senate account still had money after the elections ended.

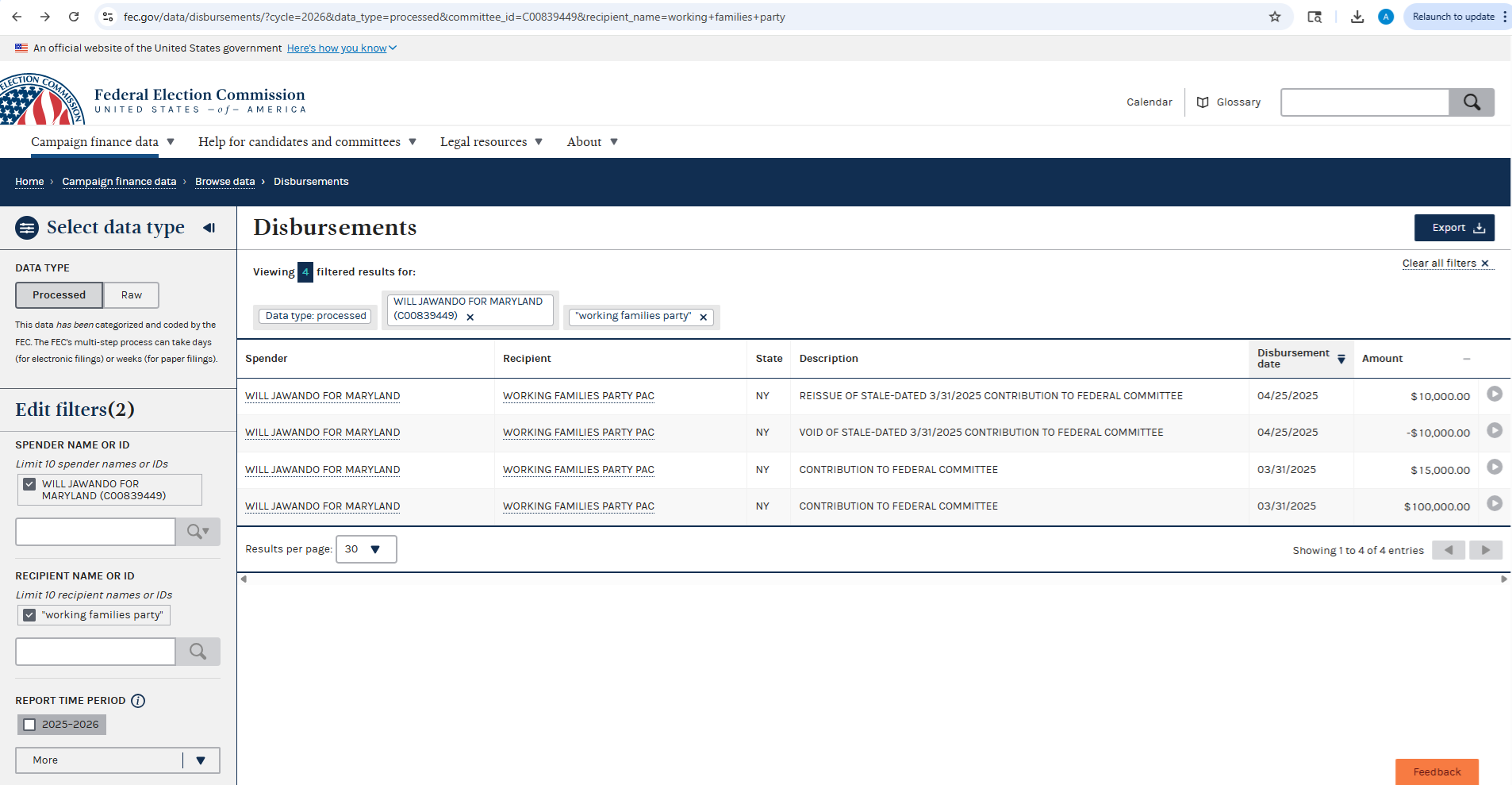

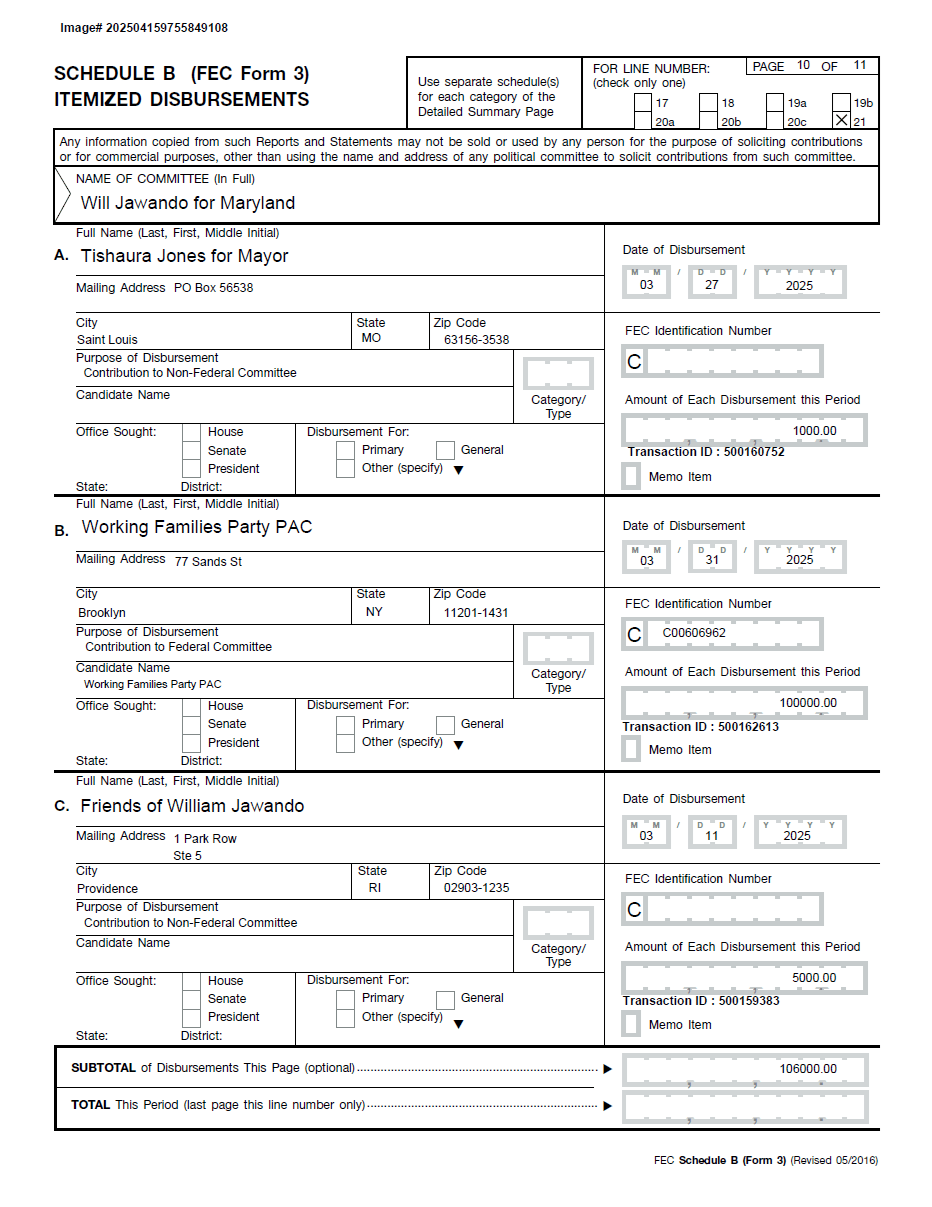

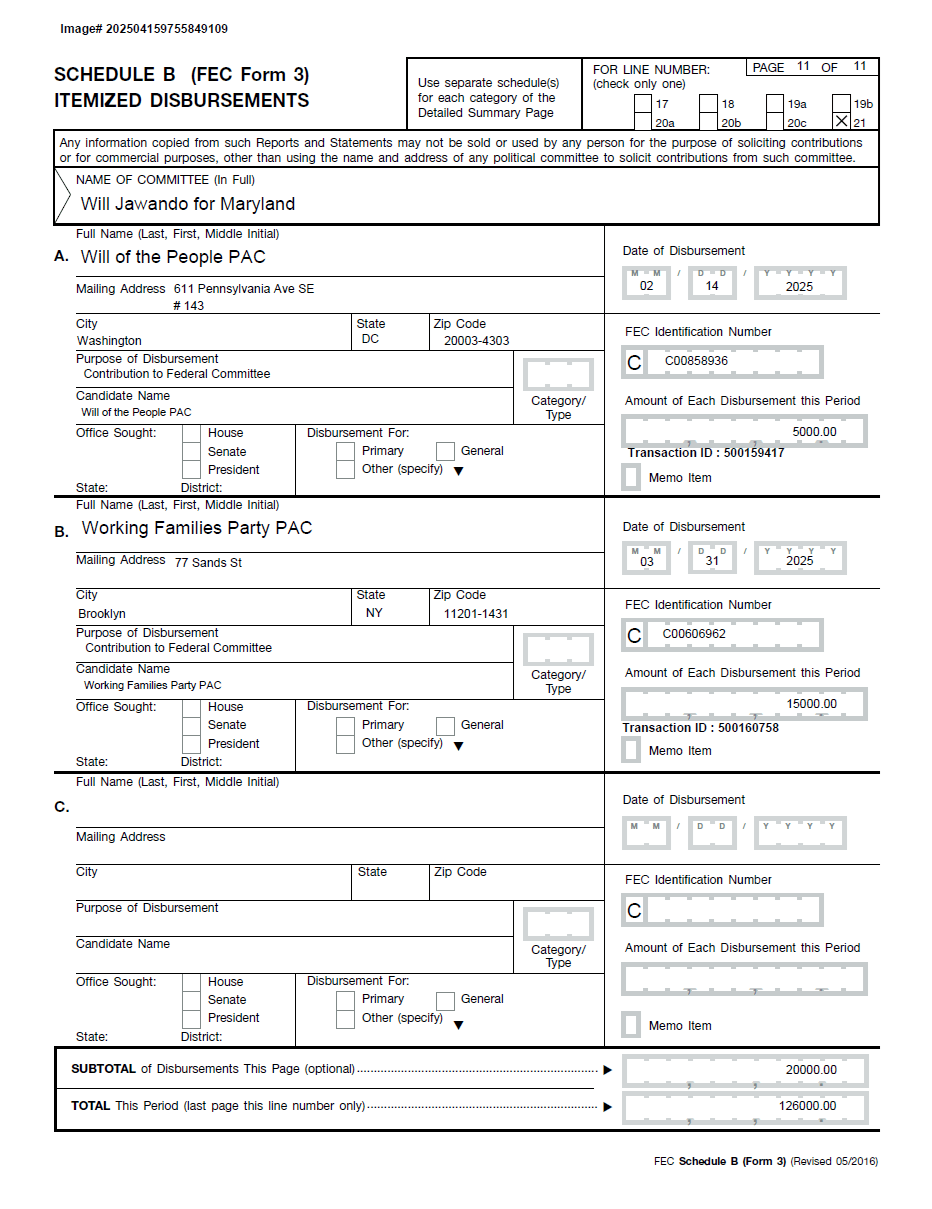

On July 15, 2025, Jawando terminated his U.S. Senate account. Prior to its closing, Jawando used it to send contributions of $100,000 and $15,000 to the Working Families Party PAC on March 31. The images below also show contributions to his federal PAC and to his traditional state-level account (which he never closed) of $5,000 each.

In early September, WFP endorsed Jawando in a joint event with Progressive Maryland.

Again, is this ethical? Is it legal?

Let’s deal with legality first. I don’t believe that the contribution by itself violates federal or state election law. I know of no federal statute or policy that prohibits candidates, including inactive ones, from contributing campaign money to political parties. I bet this happens every single day. And state law does not cover transactions between federal accounts; it only addresses transactions involving state accounts.

However, there may be a potential legal issue if WFP uses Jawando’s contribution to finance an independent expenditure committee on his behalf in next year’s election. Md. Election Law Code Ann. § 1-101 defines an independent expenditure on behalf of a candidate as follows:

“Independent expenditure” means a gift, transfer, disbursement, or promise of money or a thing of value by a person expressly advocating the success or defeat of a clearly identified candidate or ballot issue if the gift, transfer, disbursement, or promise of money or a thing of value is not made in coordination, cooperation, consultation, understanding, agreement, or concert with, or at the request or suggestion of, a candidate, a campaign finance entity of a candidate, an agent of a candidate, or a ballot issue committee.

The key here is “coordination,” a prohibited act between a candidate committee and an independent expenditure committee under state law. If Jawando’s contribution to WFP followed by WFP making independent expenditures on his behalf constitutes coordination, he may have an issue under state law.

Furthermore, if the above scenario materializes, one has to ask whether Jawando’s contribution to WFP constitutes an in-kind contribution to his publicly financed county executive campaign. At the very least, that is outside the intent of the county’s public campaign financing law.

I have worked for political campaigns in the past. If I were on Team Jawando (and I’m not working for any candidate in this cycle), I would be adamantly opposed to conduct of the above kind. It seems likely to attract complaint(s) to the State Board of Elections by opponents and/or adversaries that would cause unnecessary headaches. (Lord knows there are enough necessary headaches in elections.)

Finally, what about ethics? That’s in the eye of the beholder. I worked at the county council in 2014 when Council Member Phil Andrews authored the public campaign financing law. I don’t recall anyone contemplating a scenario in which a publicly financed candidate had access to federal money that could be used in the ways described above. At a bare minimum, it contradicts the spirit of the county’s law as well as Jawando’s stated refutation of “big money or special interests.”

I asked Jawando’s campaign for comment on this issue on Monday night. I have not received a response as of this writing.

Let’s set aside for the moment any possible legal issues arising from the transactions described above. If Jawando wants to brandish the holy sacrament of public financing, he would do well to heed it in intent and appearance as well as technicality.

Update: On the night of November 5 (after this post was published), I received the following comment from Jawando’s campaign.

*****

When Will shut down his Federal account, he donated the remaining funds to a grassroots movement fighting for the same priorities he’s championed throughout his career: affordable rents, living wages, and great schools.

This movement challenges the outsized influence of billionaires and corporate developers who protect the status quo for themselves while blocking meaningful action to help working families.

Will is proud to have the endorsement of the Working Families Party and to fight for a Montgomery County that provides opportunity to the many, not just the few.