By Adam Pagnucco.

A person listed as a campaign coordinator by Council Member Will Jawando’s county executive campaign, which uses the county’s public financing program, was paid with money from his now-terminated U.S. Senate account and his federal PAC.

This raises issues of law and ethics.

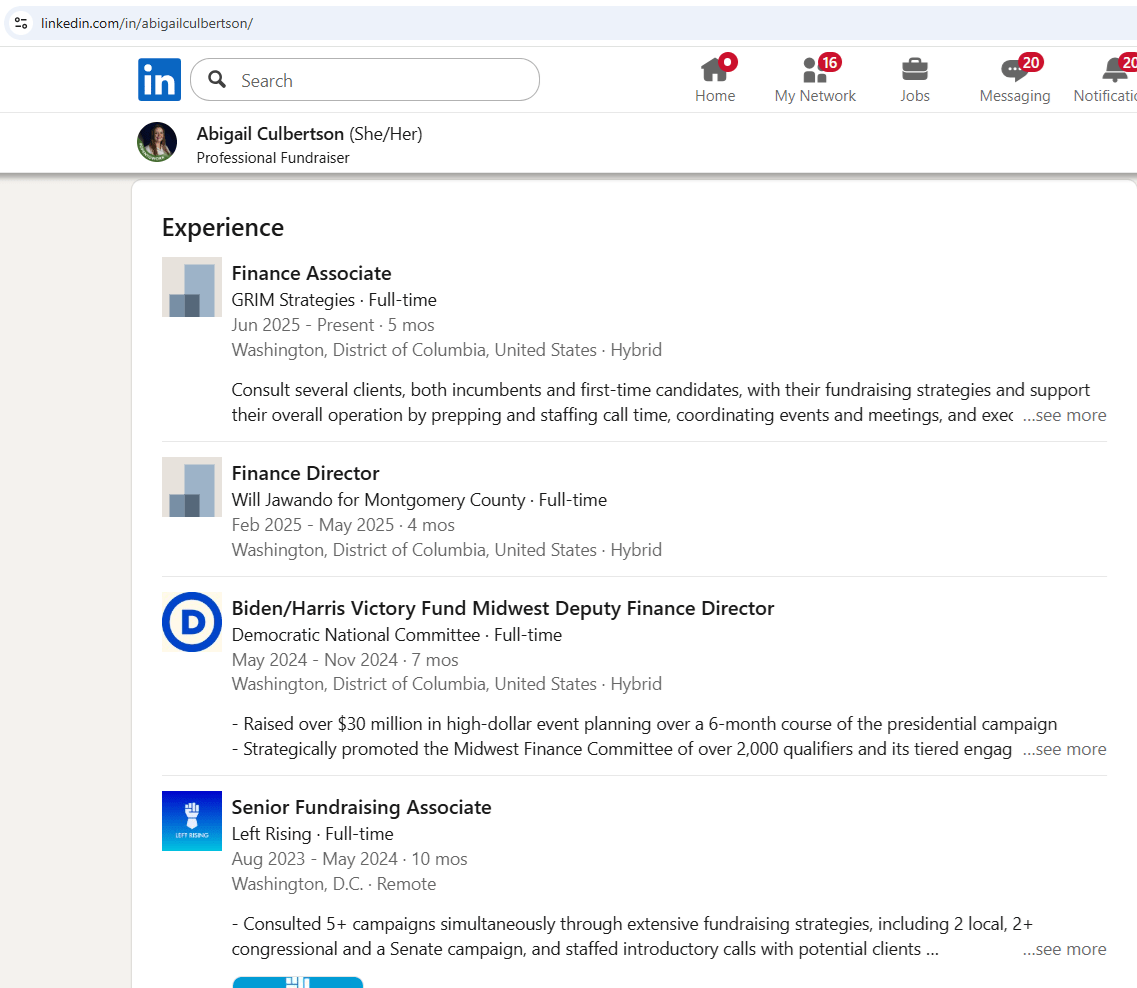

The person in question is Abigail Culbertson, a fundraiser based in Washington, DC. Her Linkedin profile describes her as “Finance Director” for Will Jawando for Montgomery County from February through May 2025.

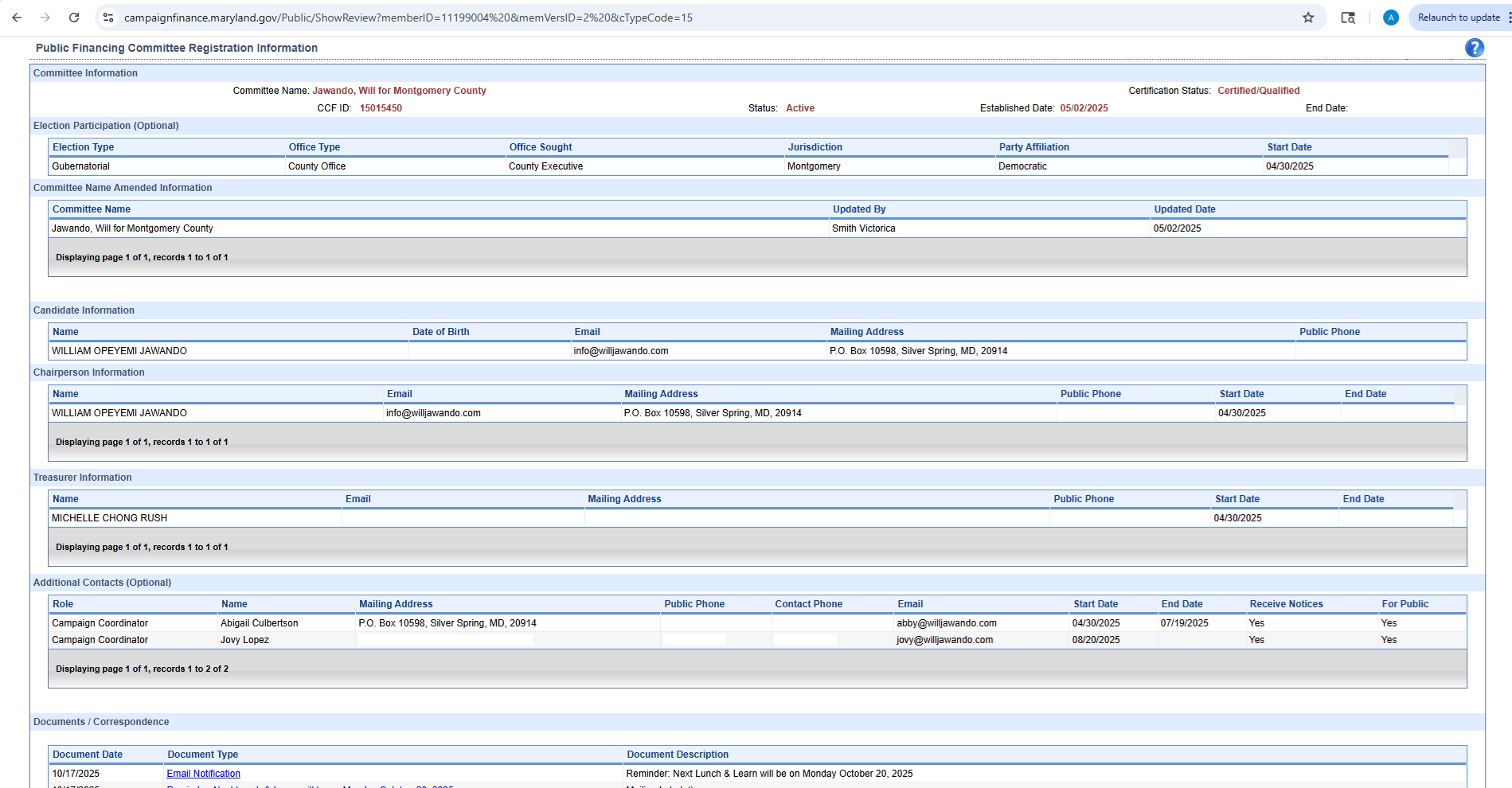

Jawando’s publicly financed campaign account, Will Jawando for Montgomery County, lists Culbertson as a campaign coordinator from April 30 through July 19. The screenshot below redacts birth dates, phone numbers and addresses other than P.O. boxes.

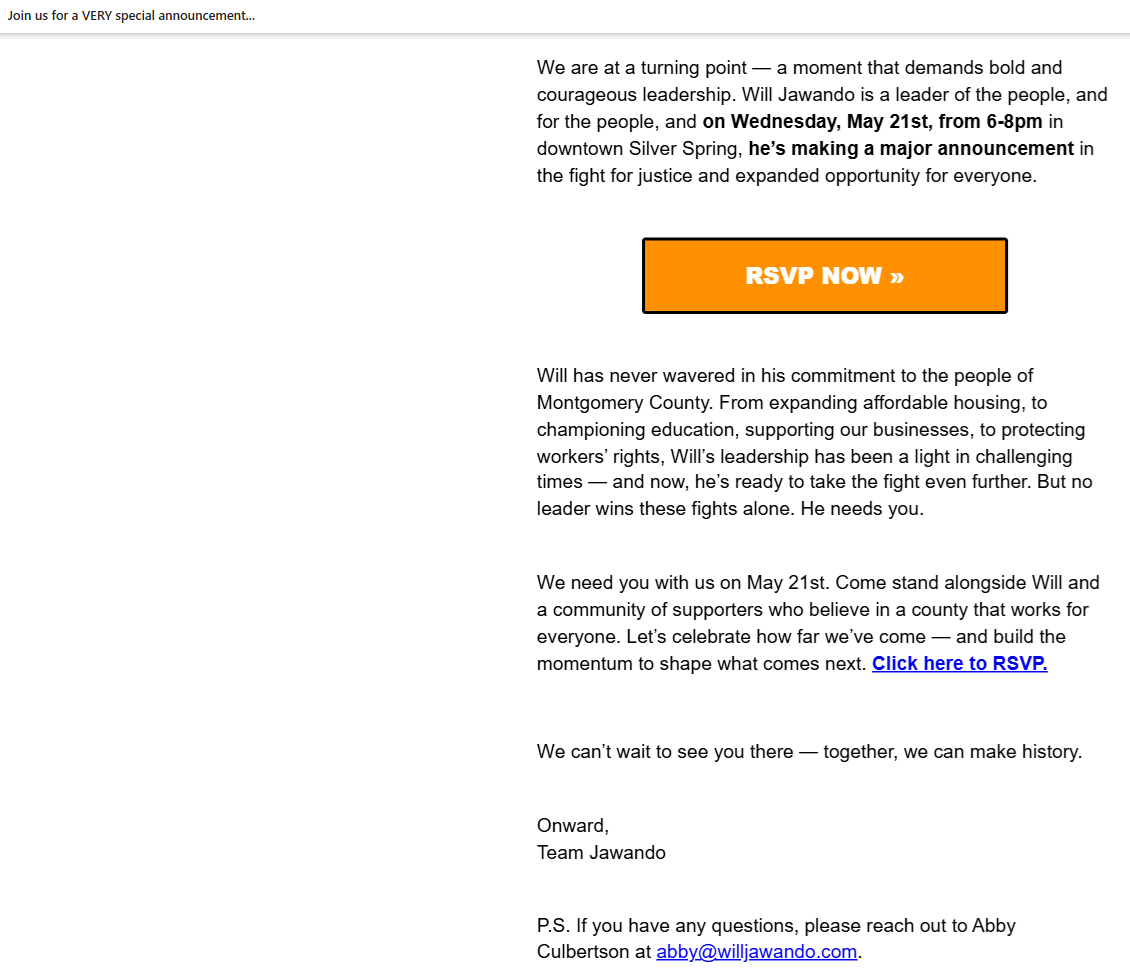

Culbertson later appeared in the flyer and email for Jawando’s county executive kickoff on May 21, confirming her association with the executive campaign.

The event flyer for Jawando’s kickoff lists Culbertson’s campaign email address. The email for the kickoff lists both her full name and campaign email address.

Expenditure records from the publicly financed account do not show Culbertson being paid for her work. Her successor as campaign coordinator, Johvet Lopez, has been paid regularly from that account.

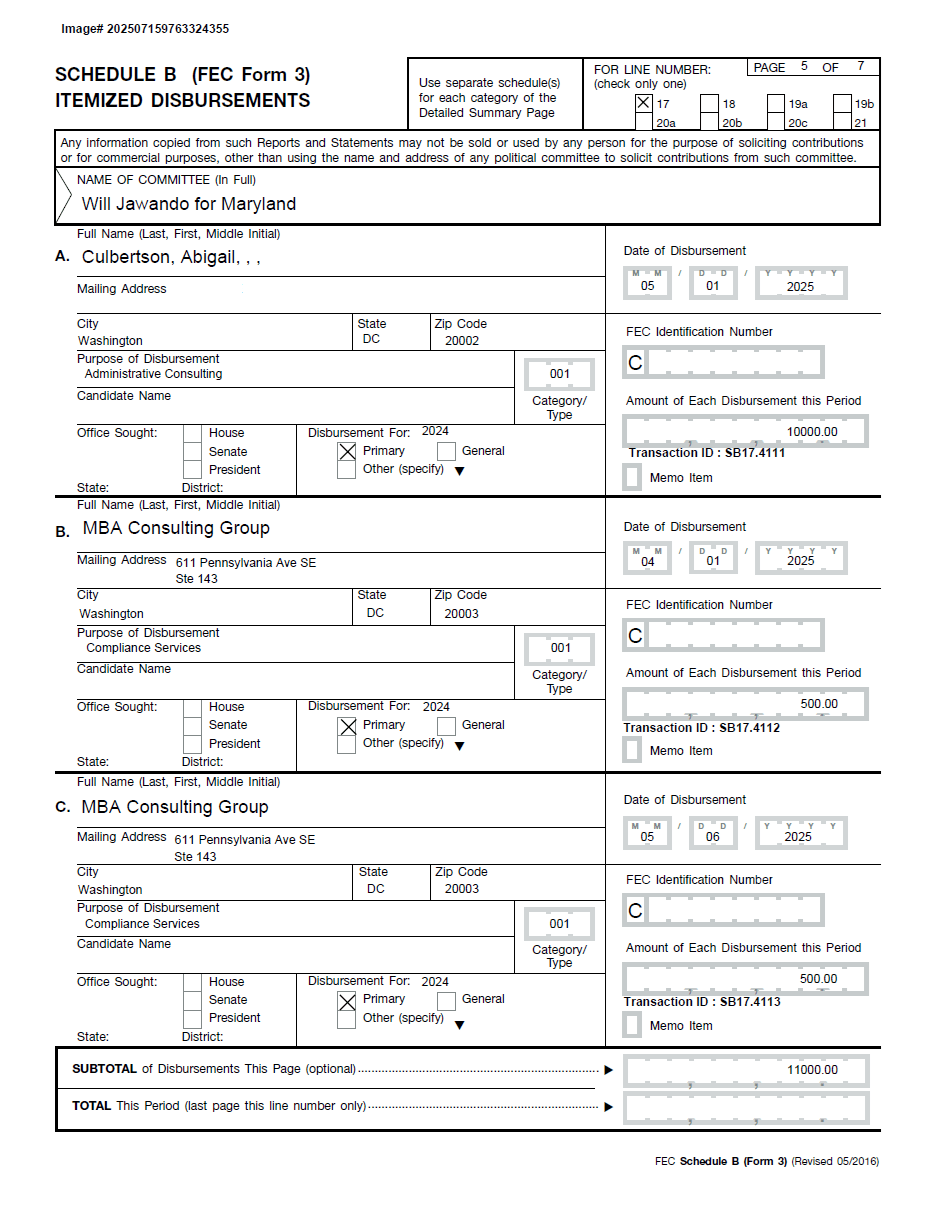

However, Culbertson was paid by two of Jawando’s federal accounts.

On May 1, Culbertson was paid $10,000 for “administrative consulting” by Jawando’s U.S. Senate account on May 1, the day before his publicly financed county executive account was established. Jawando ended his U.S. Senate campaign in October 2023. What administrative consulting was necessary for a defunct campaign as of May 1, 2025?

The screenshot below shows the payment with Culbertson’s home address redacted.

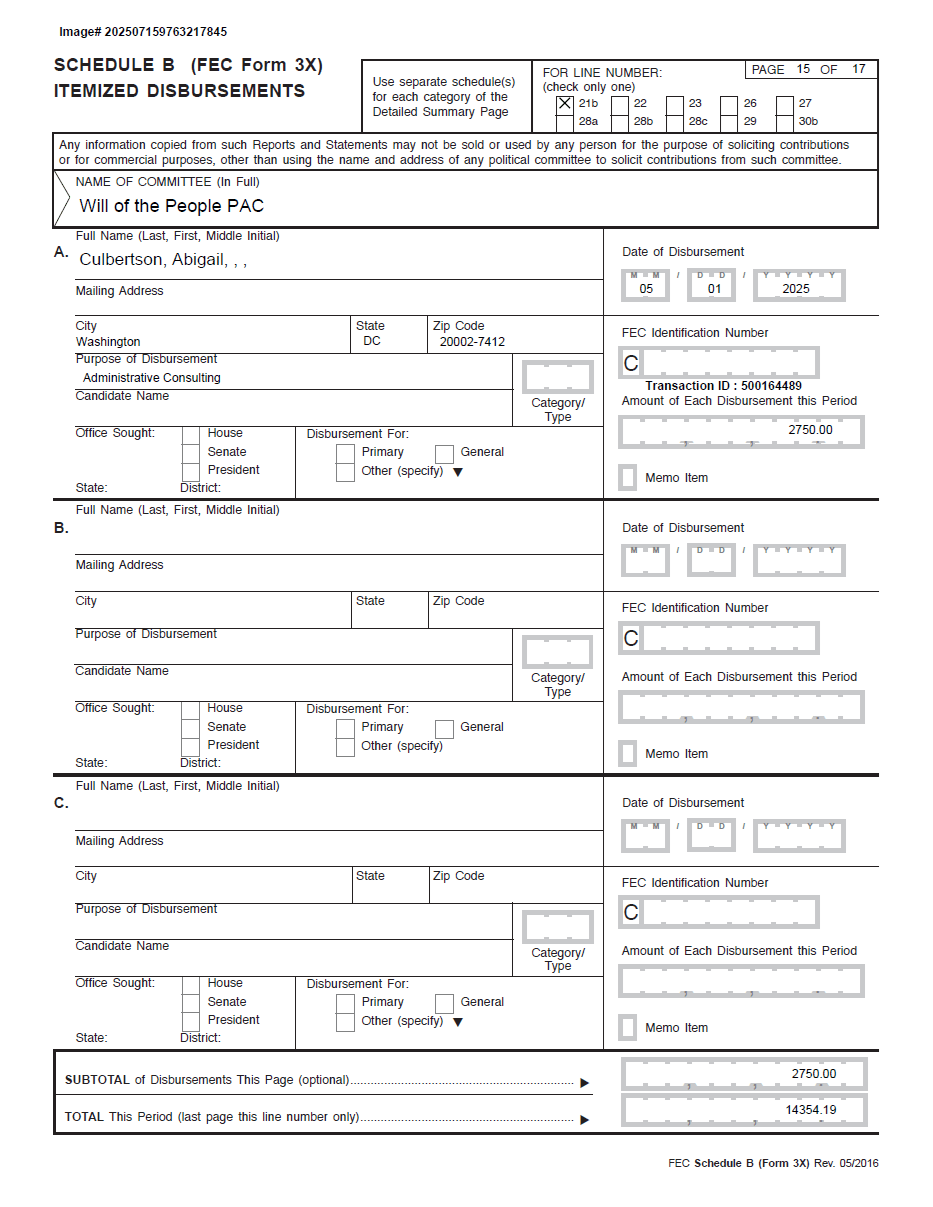

That’s not all. Jawando’s Will of the People PAC paid Culbertson an additional $2,750 for “administrative consulting” on May 1, the same day as the payment from the U.S. Senate account and – again – the day before his publicly financed county executive account was established. When Jawando established this federal PAC in December 2023, he wrote that it was “dedicated to electing a new generation of leaders who will reject the zero-sum politics of today and take real action to build an economy that works for all, protect our community from attacks on our fundamental rights, support our children’s education, and finally fix our broken healthcare system.”

The screenshot below shows the payment with Culbertson’s home address redacted.

Those were the only two payments to Culbertson listed by those two federal accounts.

This is the second issue connected to Jawando’s federal campaign accounts following his use of $115,000 in federal money to contribute to an organization that later endorsed his executive campaign.

Let’s examine election law. The State Board of Elections’ Summary Guide for Montgomery County’s Public Election Fund lists the following as an “impermissible contribution” to a publicly financed account: “A private contribution from any group or organization, including a political action committee, a corporation, labor organization or a State or local central committee of a political party.”

If Jawando’s federal PAC paid Culbertson to work on his county executive campaign and if that payment is found to be an in-kind contribution, that would be a violation of the public financing law. Furthermore, if the language pertaining to “any group or organization” applies to Jawando’s U.S. Senate account, any in-kind contribution from that account to the publicly financed account would also be a violation.

Furthermore, the summary guide states that in-kind contributions to a publicly financed account “cannot have a value that exceeds $500.00.” If the payments by the PAC and the U.S. Senate account are found to be in-kind contributions, both of them have values exceeding $500 and would therefore be in violation of the law.

The summary guide does allow some prepayments. The guide states:

*****

Assets that the candidate has paid for and received prior to filing their notice of intent to participate in the Program can be used but only in a limited capacity. Otherwise, pre-purchasing by a non-public financing committee for campaign materials or items is prohibited.

Example 1: On March 1, 2025, Candidate A contracts with a bus manufacturer to build a custom campaign bus and pays $100,000 in full for the bus to be built and delivered on July 1, 2025. On April 1, 2025, Candidate A files a notice of intent to participate in the Public Election Fund with the State Board. On July 1, 2025, upon receipt of the pre-paid campaign bus, Candidate A would be in violation of the Public Election Fund regulations which prohibit the advanced purchase of goods and services with ineligible contributions received outside of the Program.

Example 2: On March 1, 2025, Candidate B contracts with a web developer to create a campaign website for the cost of $10,000 and pays in full at the time. On March 21, 2025, the website is completed with an ongoing monthly fee of $99, which began on March 21, 2025. On April 21, 2025, Candidate B files their notice of intent to participate in the Public Election Fund with the State Board. Upon filing this notice of intent, Candidate B now pays the monthly website fee of $99 from the candidate’s publicly funded campaign account. This is considered to be an allowable expense. The candidate does not have pay for a new campaign website.

*****

Note that the above language applies to assets and not months of labor as was apparently the case for Culbertson.

I asked Jawando’s campaign for comment on Culbertson’s pay arrangements on Monday evening. As of Wednesday night at 11:30 PM, I have not heard back.

Here’s my take. Regardless of any legal issues that may arise from the conduct described above, let’s remember why we have public financing for campaigns. It was established to allow candidates to reject large contributions and money from corporations, unions and PACs and still be able to run financially competitive campaigns with public support. Taxpayers paid out $4.1 million in the 2018 primary, $1.1 million in the 2018 general, $3.5 million in the 2022 primary and $195,592 in the 2022 general to finance public matching funds.

That’s a ton of money and we will be paying more during this cycle. If we are going to pay all of these millions, we have a right to expect that recipient candidates will obey both the letter and the spirit of the public financing law. That means no games, no PAC money, no moving federal money around and the like.

Candidates who disagree should not receive taxpayer money for their campaigns.

And the conduct described above deserves scrutiny by the State Board of Elections.