By Adam Pagnucco.

From a historical perspective, the most remarkable thing about the passage of Thrive 2050 was not its contents, the pushback against it or its possible impact on the county but rather the fact that it passed unanimously. That as much as anything attests to the evolution of MoCo politics from an old political order to a new one. And while factional swings are often cyclical, this new one could be with us for a while.

For decades, MoCo politics was dominated by two factions within the Democratic Party: pro-growth and slow growth. Land use was the fault line between the two. Pro-growthers saw the county’s central challenge as economic development, which for them was synonymous with real estate development. Their solution to the problems spawned by development – traffic and school crowding – was to plow tax revenues into schools and transportation. Their problem was that tax revenues could not keep up with infrastructure needs even with numerous tax hikes, and county voters eventually tired of taxes. Slow growthers saw economic growth as a problem, not a benefit. They decried the effects of traffic and school crowding on existing residents and saw little need for new ones. However, they had no remedy for the budget headaches caused by weak economic competitiveness.

Given that framework, local politicians established themselves at various points on the growth spectrum. In the early and mid-2000s, the pro-growth faction’s leaders were County Executive Doug Duncan and Council Members Steve Silverman, Mike Subin, Nancy Floreen, George Leventhal and Mike Knapp. They were backed up by the county Chamber of Commerce’s aggressive CEO, Rich Parsons, and the Washington Post editorial board. The slow growth faction’s leaders were Council Members Blair Ewing and Marilyn Praisner and council candidate Marc Elrich, backed up by a strong county civic federation and grassroots groups like Neighborspac. Ike Leggett, always a step ahead of everyone else, bobbed and weaved in the middle. The 2002 election was a war between Duncan’s End Gridlock slate and Ewing’s group, culminating in a crushing – although temporary – pro-growth win.

In that environment, it would have been impossible to imagine something like Thrive 2050, with its promulgation of new housing across the county, passing unanimously. Ewing, Praisner and their allies would have done everything possible to kill it or, if they couldn’t get the votes, weaken it into irrelevance before approving its shattered skeleton. Elrich would have whipped the civic community into a frenzy over it and tried to ride it to an election victory. Indeed, nothing as sweeping as Thrive was even proposed because everyone knew such a thing would have ended in conflagration.

So why is today different?

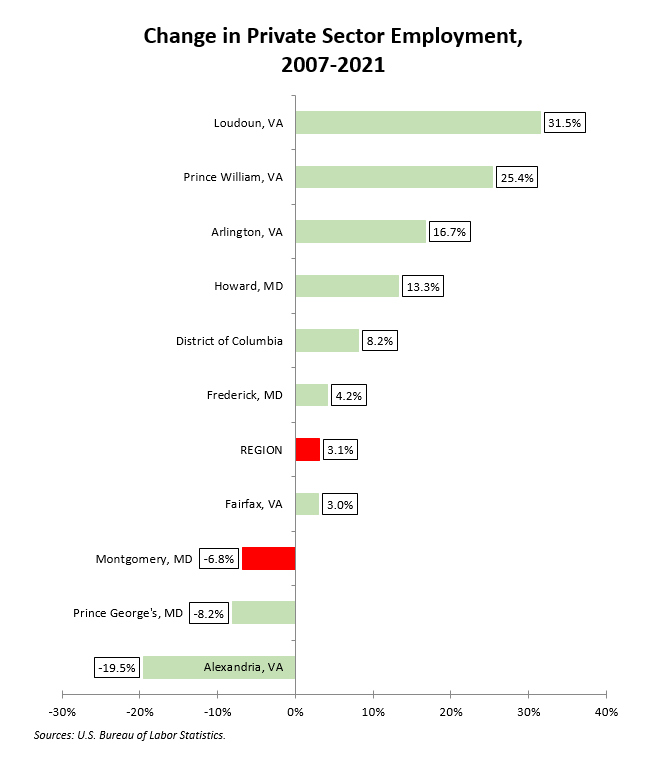

The county’s circumstances have changed greatly over the last 20 years. After strong growth in the early 2000s, the county crashed in the Great Recession – trends shared by the rest of the region. But unlike most of the rest of the region, MoCo’s private sector never fully recovered afterwards. The county was no longer economically competitive with D.C. and Northern Virginia. In a shift that took way too long to make, virtually all of the county’s leaders began to express concern about economic development, something that prior generations of leaders largely took for granted. Even Elrich, one of the loudest slow growthers in county history, now says he favors job growth (although he is still skeptical of the real estate development required to enable it). The pro-growthers won the rhetorical argument, but from a policy perspective, no county leaders have solved the challenge of making the county more competitive.

In the place of land use, a new split arose – this one fed by national politics. The council developed a strong progressive wing that began to pass national progressive priorities locally – a higher minimum wage, sick and safe leave, a racial equity law with a bureaucracy to implement it, public financing for elections, various measures to crack down on police, new protections for tenants and janitors, guaranteed income payments and even rent control (if only temporarily). In reaction, more moderate voices quietly attempted to trim back some of these priorities for fear of getting too far out of line with the rest of the region, not to mention too far ahead of the voters.

Both sides – and I hesitate to call them “sides” because the boundaries are fluid and sometimes situational – have embraced the smart growth community’s view of land use, particularly on housing. One wonders whether the unanimous passage of Thrive 2050 has ended the ability of land use disputes to decide elections. Few candidates in this past election other than Elrich even bothered to run against Thrive, something that would have been inconceivable in Blair Ewing’s heyday.

Instead of positioning themselves on a land use spectrum, today’s politicians position themselves on a spectrum between the center left and the far left. Will Jawando, armed with his recently published memoir and a willingness to push the left’s priorities as far as he can take them, may be the most prominent leader of the progressive wing. Jawando’s competition includes Evan Glass, who is almost as progressive as Jawando but not quite as full-throated about it, and new Council Member Kristin Mink, who might be even further left than Jawando. Andrew Friedson, armed with strong support in the county’s wealthiest communities, an overflowing war chest and a legislative cunning that belies his youth, is the unquestioned leader of the center left. Gabe Albornoz is trying to play Leggett’s former role of moving around in the progressive middle. And then there’s Elrich, the last king of the slow growthers, still possessing the power of the executive but isolated from the play at the council, where the county’s future will be decided. Waiting in the wings are the interest groups, ever eager to extract their pounds of flesh regardless of where the county is headed.

The old political order ended with a whimper in the ashes of the Great Recession. How will this new order play out as MoCo enters the next chapter in its history?