By Adam Pagnucco.

Let’s resume evaluating Elrich’s pushback on the council over its recently passed FY24 budget.

On school spending

Elrich took two tracks on school spending.

First, he remarked that in real inflation-adjusted dollars, the county’s local per pupil contribution to schools is lower than it was before the Great Recession. He is right about that. I made that argument myself seven years ago. The reason for that is that the county went to war with Annapolis over cutting schools during the recession that ultimately culminated in important changes to state law, including the current loophole allowing tax hikes to bypass charter limits. I told that story in The Hand of the King.

But while Elrich is correct, this argument is incomplete because it does not address how MCPS spends its money. I wrote a five-part series on teacher salaries that found that MCPS never spends its full appropriation of instructional salaries, that it regularly diverts them to other categories of spending and that it has been building a large fund balance. Later, I dissected its fund balance to reveal that it has tens of millions of dollars in liquid assets.

It’s time for the school board, the executive, the council, the state – someone, anyone! – to do a deeper dive on how MCPS spends public money. How much of its billions of dollars in annual spending actually winds up in the classroom? Can the school district do a better job? These questions desperately need answers and it’s unacceptable for significant tax hikes to be unaccompanied by scrutiny of how that money gets spent.

Second, Elrich asserts that Montgomery County is not a regional leader in school spending. His sources and methodology on enrollment and per pupil spending have no citations so I don’t know where his numbers come from. To fact check them, I went to the state agency that collects annual data on school finances: the Maryland State Department of Education (MSDE). Let’s look at three key measures of school finances for all 24 of Maryland’s school districts.

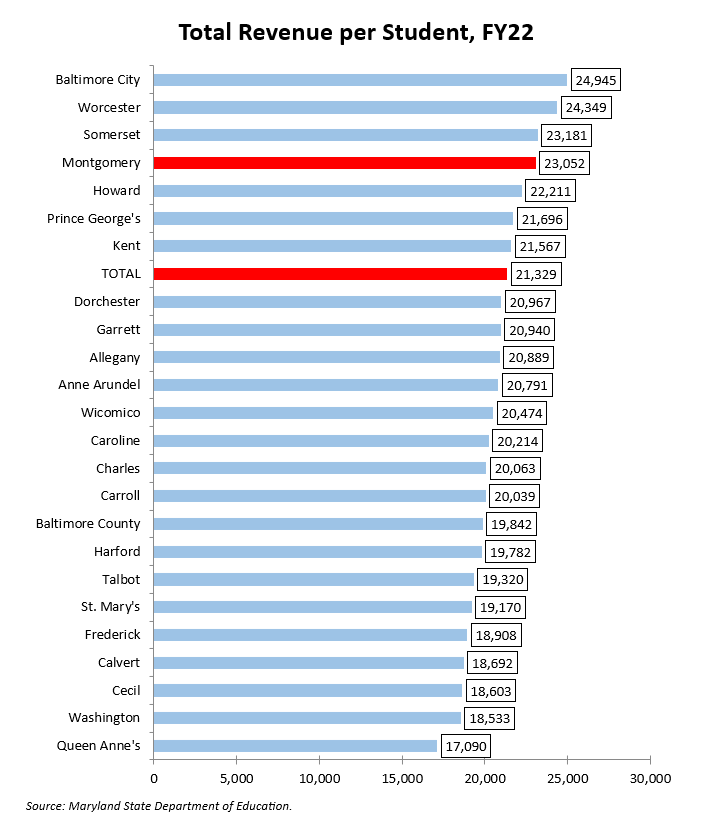

First up is total revenue per student. This includes local money, state and federal money, grants and internally generated revenues (like fees). This also includes current expenses, school construction, debt service and food service, making it a much broader measure than the operating budget by itself. The chart below shows this data point for all of the state’s school districts in FY22.

Montgomery County ranks fourth. Worcester County, which along with Talbot, Howard and Montgomery is one of the wealthiest counties in the state, ranks second. Baltimore City and Somerset County, two of the poorest jurisdictions in Maryland, rank first and third respectively because of disproportionately large infusions of state aid.

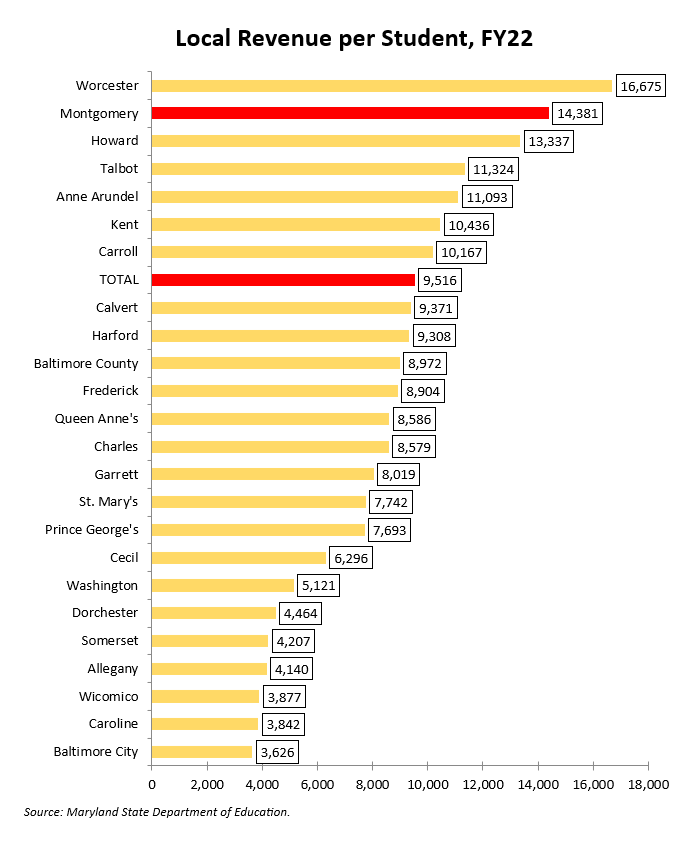

Now let’s look at local revenue per student. This includes local appropriations used for current expenses, school construction, debt service and food service. Counties don’t control state and federal aid, but they do control their local appropriations subject to state floors.

On this measure, Montgomery County is second. Only Worcester County, which enjoys a wealthy property base in Ocean City, ranks higher.

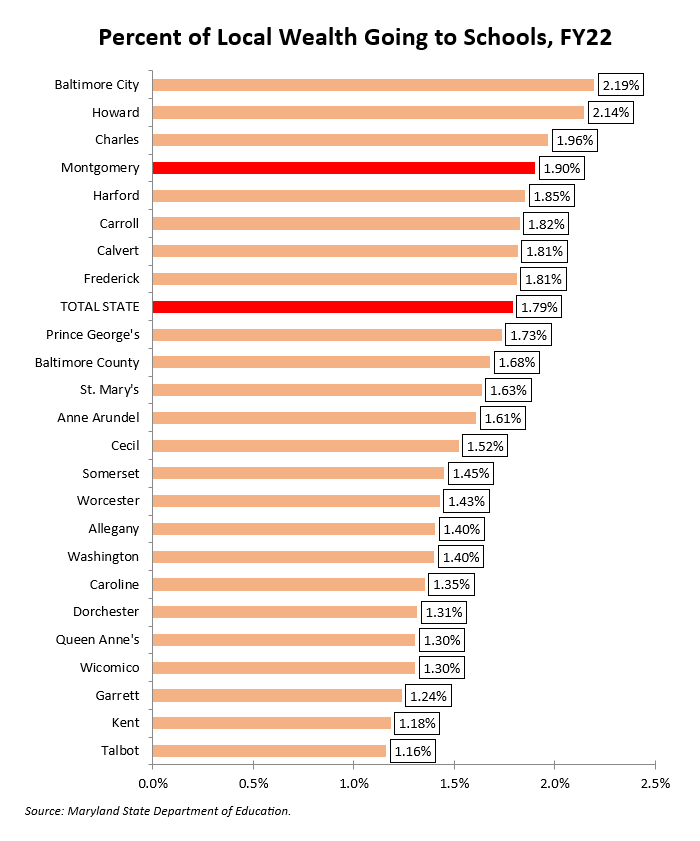

Finally, let’s look at the percentage of local wealth the counties spend on schools. The state defines local wealth as “taxable income, real and public utility property assessments for state purposes and 50% of personal property assessments for county purposes.” This measure takes into account how counties spend on schools relative to the resources possessed by their economies.

Here, Montgomery County is fourth. Baltimore City is number one, meaning that while they may have a struggling local economy, what the city can spend actually goes to schools.

So what does all of this mean? Montgomery County compares well to most of the rest of the state on school funding. Perhaps that’s not good enough. Perhaps we should strive to be number one on all of these measures. We and Howard County are the only two jurisdictions that have a real shot to do that. But to achieve such a goal, we need to restrain spending growth in the rest of our county government to do it without repeated tax hikes. Restructuring government, which this executive has not done, is the key to getting there.

Property taxes are higher in Northern Virginia

This is one of Elrich’s favorite points and he has made it repeatedly over the years. He wrote:

Fairfax collects a lot more money from their property tax – over $3 billion while we collect about $1.9 billion. They collect more than a billion dollars more than us and they are not much bigger than we are. Plus, they’ve just lowered their property tax rate to 1.09 cents, which is still higher than what ours would have been with the 10-cent increase I proposed. My proposal would have brought us to almost 1.08 cents. The Council’s rate will be at 1.03 cents, significantly lower than Fairfax newly lowered rate…

If increasing the property tax is deemed too burdensome for residents, then we need to look elsewhere. Repeatedly, I have shown that our commercial properties are undertaxed as compared to DC and Northern Virginia.

Both commercial property owners and homeowners are paying higher property taxes in Northern Virginia. At the same time, there are people who say that people don’t want to come to Montgomery County because of high taxes. The reality is different.

He is right – Fairfax County does have higher property tax rates than we do, although they have cut their rate three years in a row. Loudoun and Prince William counties have lower rates. But comparing property taxes by looking at rates can be deceptive. We have a $692 income tax offset credit for homeowners that drops our effective tax rate. After all of these credits are calculated, I wouldn’t be surprised if Elrich is correct about this in the end.

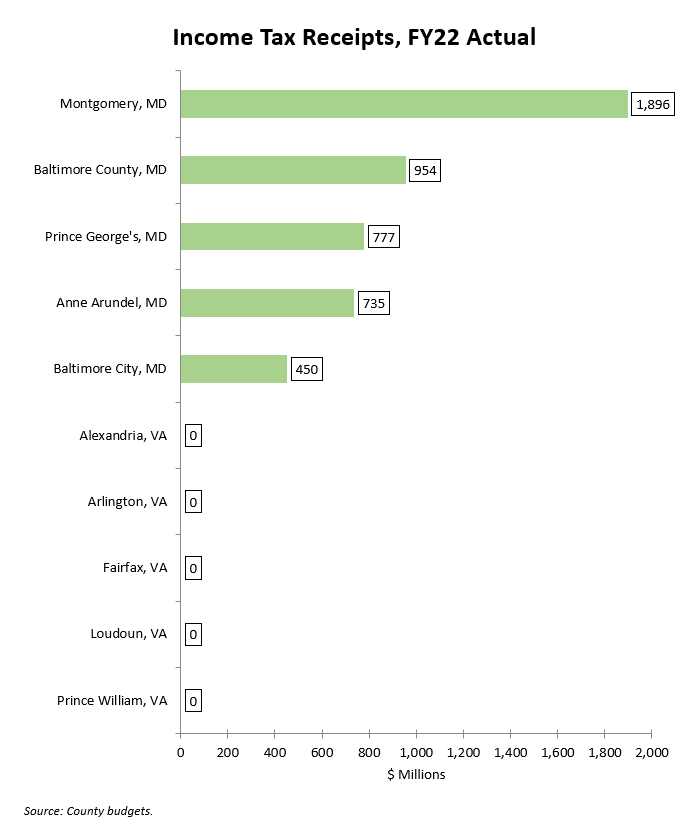

But here is what Elrich is not telling you: the reason why many Virginia localities have higher property taxes than we do is that they are unable to levy income taxes. So OF COURSE they need to charge more in property taxes. The chart below shows income tax receipts in FY22 for the five largest local jurisdictions in Maryland and the five largest local jurisdictions in Northern Virginia.

See that $1.9 billion in income taxes that MoCo gets? That’s $1.9 billion that Fairfax can’t touch. And it’s $1.9 billion that Elrich doesn’t mention.

New rule – whenever anyone says that property taxes in Virginia are higher, I will remind them that Virginia counties don’t have income taxes.

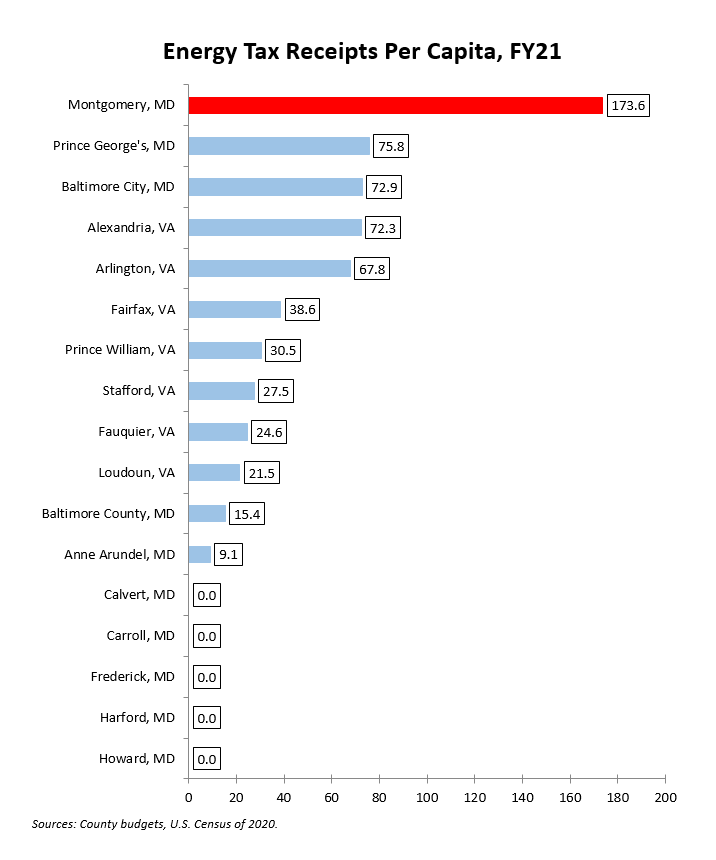

And here is one more thing: Montgomery County charges FAR more in energy taxes per capita than any other jurisdiction in the region. Check out the chart below.

So overall, Elrich is sometimes right, sometimes not right and often omits critical context in his pushback against the council. I have to admit, I love a good fight and part of me admired Elrich’s defense of himself and his administration. Give him credit – he never backs down against his critics.

But I am mystified that the council gave him 98% of the spending he wanted and he still chose to attack. I am sure that the council will not forget this as they move on to future issues, many of which will feature renewed conflict with their county executive.