By Adam Pagnucco.

On Monday, the county council’s Public Safety Committee voted 2-1 to oppose Council Member Will Jawando’s bill prohibiting consent searches by police. That’s not what bill advocates were hoping for, but they may have scored a consolation prize. How should we now assess the years-long effort to limit police power in Montgomery County?

First some background on the bill. Jawando introduced a far-ranging bill to limit police traffic stops in February 2023, but Attorney General Anthony Brown issued an opinion holding that most of it was preempted by state law. Jawando responded by introducing a new bill in February of this year with a non-preempted component prohibiting police consent searches which he calls the Freedom to Leave Act. This bill was considered by the public safety committee on Monday.

Jawando’s weak position was apparent in two ways. First, his bill has no co-sponsors. Second, he proposed a series of amendments in the committee packet that weakened the bill. One amendment replaced the bill’s prohibition on consent searches – its core provision – with a requirement that “reasonable suspicion” be present before a search. Legislators holding strong hands seldom, if ever, preemptively weaken their own bills prior to their consideration by colleagues.

Jawando, who is not a committee member, attended the session to defend his bill, but it was subjected to withering opposition by panelists from the county’s law enforcement community. Police Chief Marc Yamada argued that consent searches “are a valuable tool for us to use to accomplish our mission.” He extensively discussed the role of vehicles in transporting guns and drugs around the county, specifically mentioning fentanyl, and mentioned that the county employs a retired circuit court judge to train officers on constitutional requirements for consent searches. Looking for guns and drugs in vehicles is a top priority for police, and they are reluctant to give up any tool – including consent searches – that would help them accomplish those tasks.

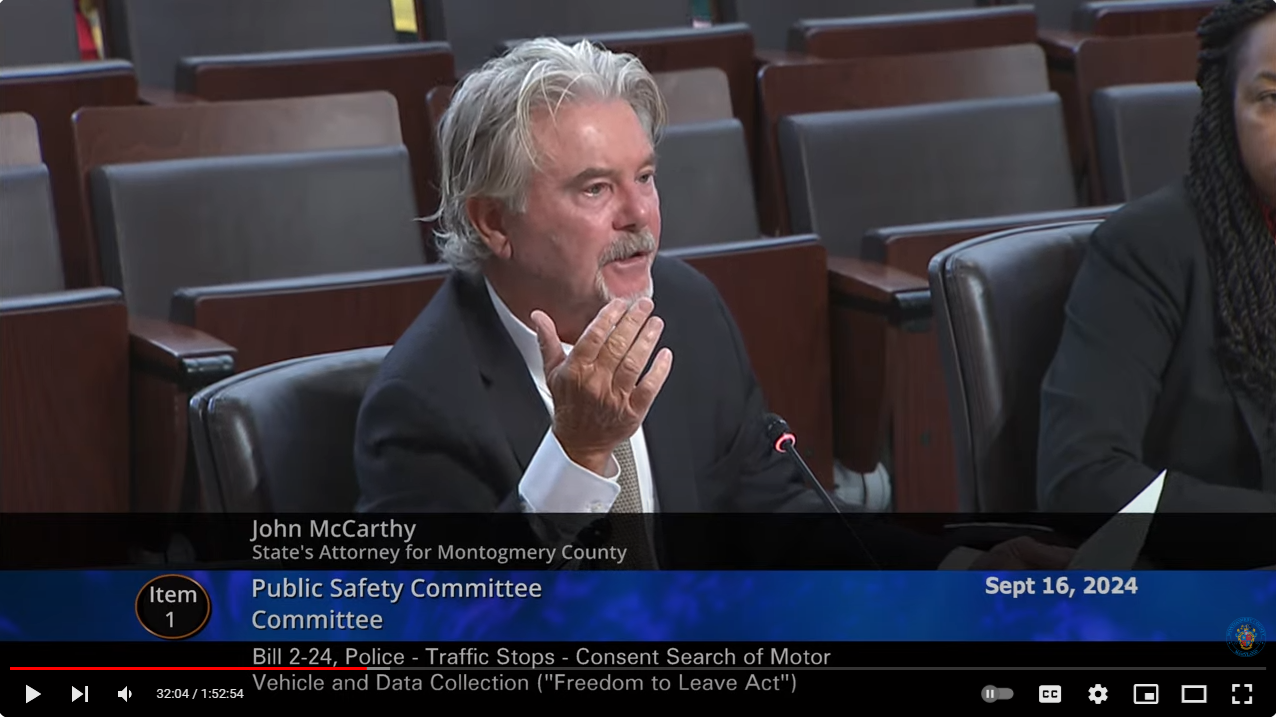

But the most effective opponent of Jawando’s bill was State’s Attorney John McCarthy. (Prosecutors are generally known for their debate skills.) Unlike Yamada and his police officers, McCarthy is an independent elected official and depends neither on the county executive nor the county council for his job. That freed him up to eviscerate the bill.

McCarthy began with this statement:

One of the things that we seem to be – that is lost in this conversation is the fact that we have video of all this. I mean, I’m looking – I look at what the bill requires the officer must now collect in terms of data… Why did we invest millions of dollars into recording exactly what’s happening here and then not only does it answer I think almost every single one of these questions, it’s already memorialized by video already by what we have done here and the investment we have made as a community.

State’s Attorney John McCarthy, the county’s prosecutor.

Under questioning by Council Member Dawn Luedtke, McCarthy confirmed that body camera video could be used by defense attorneys and reviewed by judges if it showed misconduct by officers using consent searches. Montgomery County Police Department (MCPD) representatives said that the county had been using body camera videos for a decade. So if video can be used to prevent abuses, what problem is Jawando’s bill trying to solve?

McCarthy added that he has eleven new people “just looking at body camera every day, we are so overwhelmed with it. And I will tell you consistently I get the feedback about the professionalism of the men and women that work as police officers in this county.” McCarthy also asserted that consent searches have “never” been the topic of complaints filed against the police, an allegation that got pushback from Jawando and Council Member Kristin Mink.

Mink defended the bill as requiring that the county do “better” than the standards established by the U.S. Constitution. Mink took on McCarthy’s contention that consent searches were not the subject of formal complaints by contending that the public needed to be better educated about how to file complaints against the police as well as more comfortable in doing so. This is what she said:

The concerns and complaints that we heard at the public hearing were very moving. So I want to make sure that it’s clear that there are concerns and complaints out there. So if we’re missing them through our formal complaint system, I think that’s reflective of maybe more – you know, we need to find more ways to inform and educate the public about how to register complaints formally or to make people comfortable to do so or let them know, what their rights and risks are – all those sorts of things – but I think it’s important that we, you know, that we acknowledge that we know that those concerns and complaints are out there. And that’s part of what is calling on us to do better at this moment.

Council Member Kristin Mink.

And so Mink’s response to the absence of formal complaints about consent searches is to encourage her constituents to create some. Most employees would not appreciate serving under overseers who desire more complaints to be filed against them. Nevertheless, Yamada – the police chief – bent over backwards to accommodate Mink. Later in the discussion, he told the council, “One thing if I could say about the complaint piece – if you all could help us, if you want… if we want to better educate, I ask you as the council members to go back to your constituency and say if you’ve been mistreated, if you are the victim of a violation of your rights, you all need to tell your constituency to make the complaint. That’s how we get better. I would appreciate that.”

Police Chief Marc Yamada.

Assistant Chief Administrative Officer Earl Stoddard and Mink alluded to policy changes under consideration by MCPD intended to address concerns about consent searches. Yamada mentioned that video of consent searches might be subject to mandatory review by supervisors as is done with video of use of force. He also raised potential changes connected to the use of “reasonable articulable suspicion” in initiating consent searches akin to one of Jawando’s proposed amendments. So from a policy perspective, Jawando’s bill has had an impact even if it is not passed. Jawando himself claimed credit for gathering public input on the issue and questioned whether any changes would have occurred without his legislation.

Ultimately, three factors damaged the bill, perhaps fatally. First, the presence of video as pointed out by the prosecutor limited the added value provided by the bill. Second, MCPD’s upcoming policy changes – though not yet final – could be used to argue that the bill is moot. Third, Luedtke and Council Member Sidney Katz claimed that the bill would create public confusion about police policy because it would only affect MCPD and not other departments operating in the county. (One wonders where that argument was when the council passed previous bills regulating MCPD procedures.)

Luedtke made a motion to oppose the bill out of committee and request that the full council receive a briefing on MCPD’s new policy on consent searches. After much confusing parliamentary discussion, Katz seconded the motion. Luedtke and Katz voted to oppose the bill with Mink dissenting, a 2-1 vote against it.

Is the bill dead? Luedtke posed this question to a council staff attorney: “My understanding is that if a bill does not have a favorable vote out of committee, in order to be heard on the bill – not the policy, put that in another bucket – in order to be heard on the bill, and then subsequently amend the bill, tweak the bill, whatever you want to do to it – in order for that bill to be heard by full council, six members of the council have to request that it be heard by full council. Is that correct?” The staff attorney confirmed that was correct.

Jawando’s bill has no co-sponsors, not even Mink. Reader, you tell me whether he can get six votes to get it on the full council agenda.

Last month, I asked whether the movement to end police traffic stops was dead and cited this bill’s fate as a factor. One thing that’s apparent is that advocacy to limit police power is not dead. Those voices are still being raised and Jawando and Mink are their champions. But the council is not in the same place as it was just a few years ago, when it passed a series of bills regulating police activity. The public has been fed up with crime for some time. All elected officials are concerned about – or at least say they are concerned about – the proliferation of guns and lethal drugs like fentanyl. So the enthusiasm for restricting police activity has definitely been dampened.

Looming over all of this is a potential police staffing bomb in which a change to the pension plan could drive a huge wave of officer retirements as early as this coming January. If that bomb goes off and rampaging criminals gleefully run free in the streets, no politician – even Jawando and Mink – should expect to be held blameless by vengeful voters.