By Adam Pagnucco.

After an incredible 33-candidate council at-large Democratic primary in 2018, this year’s race featured a much more manageable 8 candidates. Three – Gabe Albornoz, Evan Glass and Will Jawando – were incumbents running for a second term. One – Tom Hucker – was a district incumbent who had switched to run at-large. Another – Brandy Brooks – had lost respectably in 2018 and was running again. Two others – Laurie-Anne Sayles and Scott Goldberg – had run unsuccessfully for delegate before, although Sayles had won a race for city council in Gaithersburg. One seat was open as term-limited incumbent Hans Riemer ran for county executive. The top four finishers would win.

The race saw two huge curveballs. First, Brooks got involved in a huge scandal with a campaign staffer, causing her to lose multiple endorsements. Albornoz was the primary beneficiary. And second, Hucker – who had been running for executive – dropped into the council at-large race at the filing deadline. This caused consternation for all the other candidates but especially for the non-incumbents.

Council at-large races are unusual in that they involve multiple seats and are most similar to state delegate races. The person who best described the dynamic of such elections to me was then-26-year-old Jeff Waldstreicher, who was running for delegate in District 18 in 2006. I will paraphrase his take on how they work:

There are three seats at stake. I tell voters that I don’t have to be their first choice, although that would be great. I don’t even have to be their second choice. I just want to be one of their top three choices. A vote is a vote and they all count equally.

Henceforth, this shall be known as the Waldstreicher Doctrine.

The council at-large race has four seats, but otherwise, Waldstreicher’s analysis is dead on. It doesn’t matter if an at-large candidate is anyone’s first choice, second choice, third choice or fourth choice – a vote is a vote. If a particular candidate is the fourth choice of every single voter, that person would get the most votes in the election and look like the top dog. In fact, absent exit polling, there is no way to discern if an at-large candidate is anyone’s top choice UNLESS that person runs in a one-seat race like county executive or Congress. Such transitions can be extraordinarily revealing.

In analyzing this year’s race, let’s look at ten influential endorsements in the table below.

Unsurprisingly, the three incumbents received the most endorsements from this group. Hucker, who had served on both the council and the House of Delegates, and Sayles, the only woman in the race, were next. Goldberg had three but one of them was the Washington Post. Dana Gassaway was non-competitive. Brooks lost several endorsements after her scandal broke, with MCEA switching to Albornoz and Casa in Action switching to Sayles. This was critical to Albornoz since incumbents who are endorsed by both the teachers and the Post rarely lose.

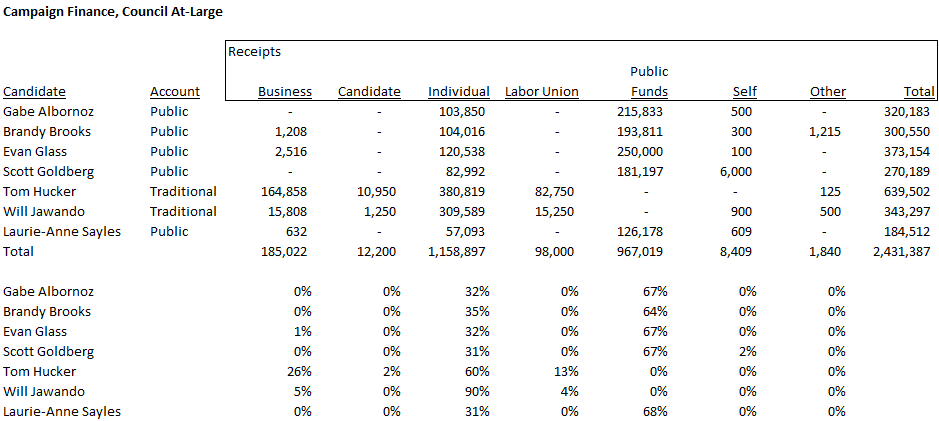

Now let’s look at fundraising.

Tom Hucker raised by far the most money of these candidates, but most of it was raised before he started running for council at-large. Evan Glass was the only publicly financed candidate to max out on matching funds. Aside from Hucker, there were not huge differences in money between the top candidates so other factors mattered more. (Dana Gassaway, who finished last, has not filed any campaign finance reports as of this writing.)

Here’s an interesting fact about the at-large race: while each voter may cast up to four votes, not everyone uses all of them. This year, 145,705 Democrats voted in the primary and 467,015 votes were cast for council at-large candidates, meaning that the average voter cast 3.2 votes in the at-large race. This is typical of past elections; it was 3.1 in 2014 and 3.3 in 2018.

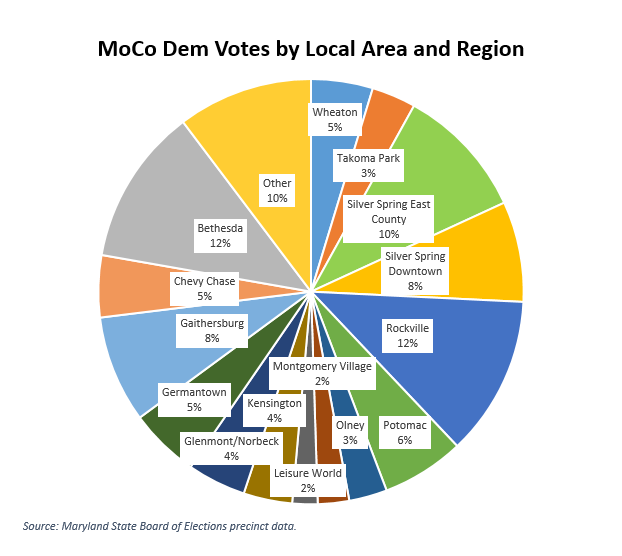

A final observation: the pie chart below shows the distribution of votes by geography.

Here is today’s Captain Obvious moment: this is a big freakin county and there are lots of places to go get votes. Downcounty draws the most attention because of its high turnout rates and frequency of political contributions, which is amplified by public campaign financing. But there is more than one path to getting elected in countywide races and this cycle provides examples.

We will begin looking at the candidates in the next post in the series.